Żmijewski’s uneducation * / Žmijevska at-izglītošanās *

ENG

Rather than face this ragged image, the critic turns to the fluids of sexuality, the gloss of lubrication, the glossary of the body as text, the heteroglossia of the intertext, the glossolalia of the schizophrenic. But almost never the body of the differently abled.[1]

This image: a naked artist sits on the ground with his legs crossed and arms wide open, ready for close encounter, encounter with the other and with the possible danger the other may befall. Before that naked people were running and bursting into one another in slow motion. This work is called Me and AIDS (1996), and now, after more than 20 years later, when AIDS is less of a threat, it still seems very up to date. Whenever I think of him, I see Żmijewski as this naked man whose exposed self invites and receives considerable number of stimuli, ambivalent rather than painful, which he then translates accordingly with his procedures of engagement into images travelling among various layers of discourse and on the sideways of the visible, acceptable and appropriate.

At the time when Western humanities saw the coming to life and growth of disability studies as a separate and independent discipline, Żmijewski began his works not on or about, but with the disabled. Both academic and artistic activities seem to have been founded on a similar conviction, namely that disability belongs to a minority rather than medical discourse. At the same time these activities have criticised oppressive narratives and pointed towards emancipatory solutions. In this new framework, the experience of the disabled has become analogous with that of women, people of colour, non-heterosexuals and queers. Żmijewski’s socially applied artistic labour focuses on working against the blind spots of the otherwise very self-assured community of the onlookers. Meticulously he studies the moments of exclusions and critically investigates the rules of inclusion, and provides space for the forms of self-expression of hitherto unwelcomed subjects such as humans whose abilities are limited.

Żmijewski’s persistence on looking at the differently able is as much political as it is artistic project which has power to transform the rules of visuality.

Lesson 1: B for body

When looking back to the past three decades one could argue that the body (with its disabilities and illnesses) has become an abject Other which haunts body art, performance art and video art – its theories and practices – on the one hand, and the history of post 1989 political and social transformation in Poland, on the other. Żmijewski’s persistence on looking at the differently able is as much political as it is artistic project which has power to transform the rules of visuality. The artist claims his “right to look” and, in doing so, points to the history and the now-time of the regimes of vision[2]. As did Diane Arbus, Roger Ballen, Richard Billingham, Boris Mikhailov, Hannah Wilke, Katarzyna Kozyra, Alina Szapocznikow, David Wojnarowicz, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Derek Jarman, Jo Spence – each one of them in their own time and on their own terms.

In this project of social pedagogy, we deal with a troubled body – a body with troubles and a body which troubles, questioning the structure of normality. To use Lennard Davis’ phrase, he helps normal people “see the quotation marks around their assumed state”[3] and investigates into disability as a social, historical and cultural construct. What we feel and think about the body (as well as in the body) has little to do with spontaneity and a lot with “ideologies of containment” and “policy of control”. The same can be said about how distinctions between able and disabled bodies work, what is perceived as a transgression and what already as deviance, when an inability to perform certain actions or functions becomes a lack, an imperfection, a visible difference that strikes and bothers. Disability – as Davis pointed out – is a specular moment[4] which is often followed by a question whether bodies with the “dis-” are worth being made visible (and in which contexts), this of course follows the question asked by Judith Butler, among others, which lives are worth to be lived and mourned. And yet one might ask, what are the conditions under which the abled body becomes a body with a dis-.

The “dis-” is a mark of deficit in an ablest world, the world of experiencing pleasure and achieving goals. The collective “normal” body, the body of the “normal” collective has shown on numerous occasions that any aberrance will be shamed as failure: a failure which connotes many things, including an aesthetic failure – a disabled body does not look good, it does not make you want it. It is not beautiful or even when it is, it is always with a necessary “but”, as in: smart but disabled, or disabled but smart. How comfortable and comforting. The acceptance comes only after an effort: try to cure, try to improve, to be as I am, so that I don’t feel the discomfort of your strangeness, so that I do not have to be interpellated; so that I do not feel you need me, so I do not feel I need you to feel good.

Lesson 2: Love Thy Neighbour

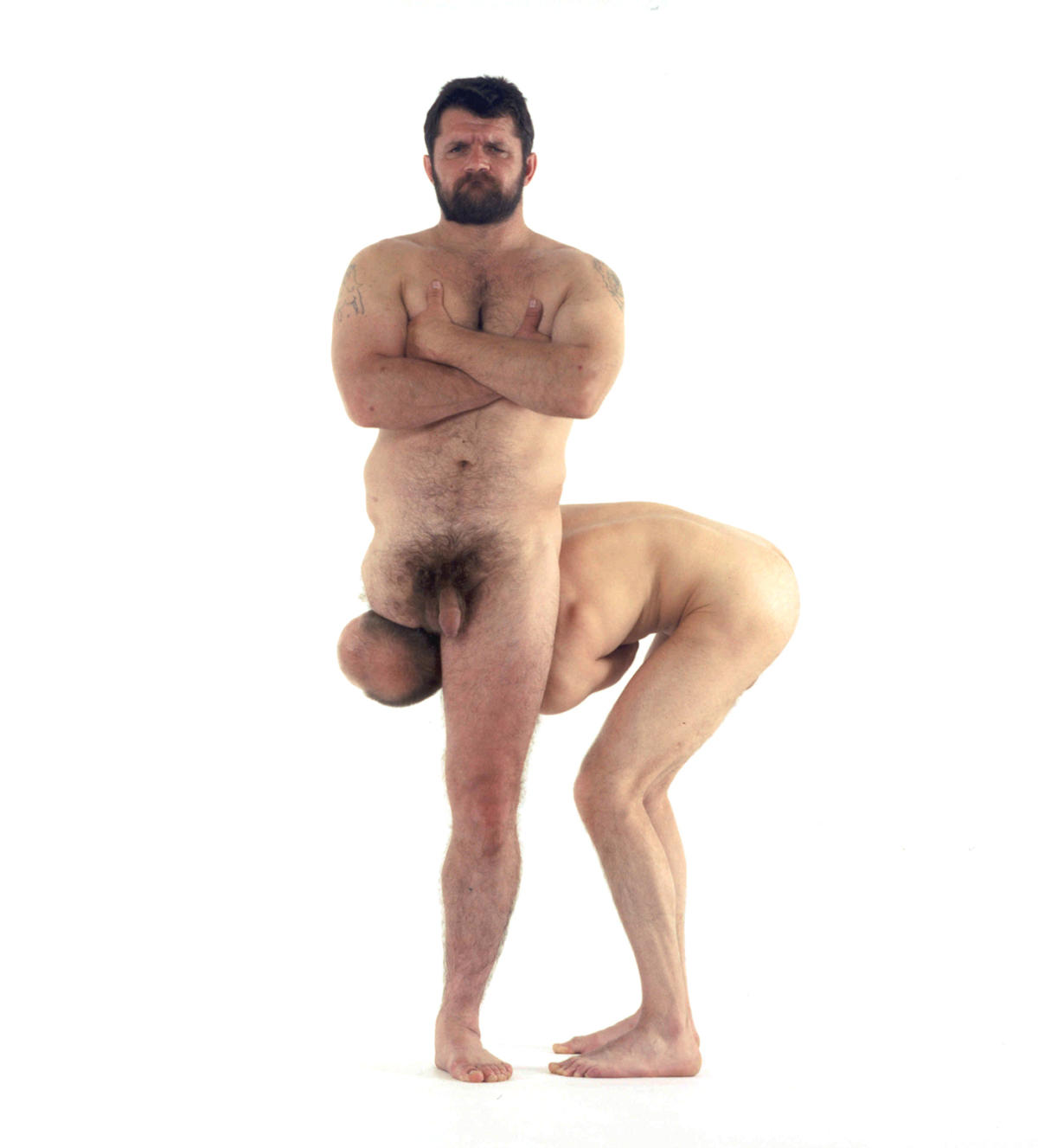

There is a vast array of affects surrounding the disabled body, ranging from repulsion, disgust and fear to empathy and pity. Żmijewski seems to test all of them, not excluding any. And yet he overcomes repulsion, the disabled and sick bodies become his buddies, his company and his responsibility, they become touchable and lovable. The love for disabled or sick body is worked through the camera, never too directly. In An Eye for an Eye (1998) the artist stages encounter between bodies with and without disabilities. They are there to perform various tasks (at times most basic ones such as walking or climbing the stairs), which highlights the difference between the bodies and their mutual dependence. The bodies are naked, vulnerable, at times, grotesque. Żmijewski studies the limits of relationality and abjection.

Is the nakedness or intimacy of “normal” and “disabled” people uncomfortable? Is the laughter forbidden?

He subverts the Old Testament call for revenge. Rather than asking for equal loss (an eye for an eye) the artist shows how to stand in, substitute, and provide mending not by means of an operation but assistance and empathy: healthy limb in place of a missing limb. In shabby-looking interiors naked male bodies lie together, walk together, jump together… The “normal” ones offer their limbs in place of missing ones of the other. This brotherhood of bodies forms grotesque hybrids who sing folk songs and perform ridiculous choreographies, as if Żmijewski was trying to distance the temptation of pity or of self-praise as much as possible. Resembling a freak show, yet substantially different. And there is also a shower-scene: a prelude to a crime or love. Young female hands serve a man to soap himself and to wash. It is the most touching sequence of gestures, which show one selfless human in the service of the other. Holding hands has never meant that much.

Is it ugly? Is it tasteless, or shameless? Is the nakedness or intimacy of “normal” and “disabled” people uncomfortable? Is the laughter forbidden? Or, should the viewer rather displace all the above matters and think-feel of something else, of something beyond oneself. When trying to situate An Eye for an Eye, I stumbled on another art work playing with substitutions and relationalities, though in a completely different context. In the notes for his Following Piece (1969) Vito Acconci wrote:

Adjunctive relationship – I add myself to another person – I let my control be taken away – I’m dependent on the other person – I need him, he doesn’t need me – subjective relationship. Fall into position in a system – I can be substituted for – My positional value counts here, not my individual characteristics.[5]

Being in place, occupying, inhabiting social spaces, moving, and being moved, following and being followed, but, most of all, getting out of oneself and becoming a link means a lot in Żmijewski’s work. If the bodies he pictures are socially and aesthetically marginalized or rejected, he brings them back, but not to be looked at, but to be present, to be made part of, to be included and to be “in touch” with us no matter how “normal” we are.

Lesson 3: Forms of Deformation

If life is constructed, how come it appears so immutable?

How come culture appears so natural?[6]

In 2001, Żmijewski made the first part of Singing Lesson[7] – performance of Kyrie from Jan Maklakiewicz’s (1899–1954) Polish Mass by a choir of deaf-mute children accompanied by an organ music at the Augsburg Evangelical Holy Trinity church in Warsaw. We see young people having fun preparing and performing what they know (or rather have been told is a work of art), we hear crazy cacophony of sounds, squeaks, wails and howls. Seeing them being easy about the whole enterprise, makes me little less stressed. For whom is this singing a lesson? How should one frame what is going on in this video? Is it a good thing to admire how they “sing”? What categories and criteria to use instead of the value judgement? The artist helps us with the statement he made about this work:

If one feels it’s “absurd” that mute people sing, this feeling comes within the logic of that terror, questioning the right of expression to those whose expression seems “imperfect,” or even does not deserve to be called expression at all.

Singing Lesson is not about transgressing the boundaries by the weaker. The outcome of their performance is not good – their singing remains crippled, deformed. This video is about failure. … One should interpret participation of the deaf singers in Singing Lesson as a refusal to please the hearing ones and an attempt at creating their own hierarchies, including aesthetic hierarchies.

The performers do not subjugate to the “terror of the able”, and the able are given space to face the terror of the dominant form: that of life and that of art. If one feels it’s “absurd” that mute people sing, this feeling comes within the logic of that terror, questioning the right of expression to those whose expression seems “imperfect,” or even does not deserve to be called expression at all. Confusion Żmijewski introduces opens a space for uneducation, for tuning to the sound of other bodily modalities; modalities rather than disabilities.

Ten years later, the artist realises performance Blindly, in which blind people are asked to paint different things; a self-portrait, a landscape, an animal. Some of the participants were born blind, others had lost sight in an accident. Listening to their conversation provides striking moments of enlightenment: “That is how I see it: it is a landscape from my head,” “Isn’t there anything missing?”, Żmijewski asks one of his male painters. “There is. Sight,” he responds boldly. (As if pointing to nonsensical or cruel idea behind Żmijewski’s work, and yet he participates). “I need to paint eyes,” says a woman who is painting a portrait. “I could use a pair myself,” she says after a while. Watching them paint and talk offers another emotional revelation. The difference between those who see and those who don’t is also one of the corporal movements: the choreography of their lives is different just as their image of the world.

Blindness and art have a long story. Blindness is a key metaphor in Western art, written about extensively; and though it is such an important matter, it rarely is present as an actual, material experience of those who do not see. The secret of insight, wisdom, imagination and memory of blind people should be tamed by the learning the culture offers them, so that they know how things look. So that we don’t have to worry what they see when they do not see. Yet another failure, this time doubled: the paintings are bad, naïve, childish, poor, or very Cy Twombly-like, interesting, provocative… and no matter how we try, we have no access to what they really do not see, only to how we trained them to miss seeing what we see.

Lesson 4: Moving with Images

Supercrip is a proper word used within disability studies to describe someone who is disabled but has some sort of genius or other skill or someone who is disabled and works hard to overcome his/her disability. In his Collection (2010–16) Żmijewski revisits the tradition of silent cinema and the times when laughing at the body’s failure was part of popular culture just as making a person with disabilities an object of ridicule. The turn of the last century and the first decade of 20th century saw numerous short slapstick films featuring “legless runners.” The artist’s collection is series of short silent black-and-white videos presenting various distorted human movements or bodies in distorted motion, caused by multiple sclerosis, spastic paralysis, Huntington’s or other disease. He also revisits the infantile fascination with difference (mixture of thrill and threat), which finds expression in staring and looking too long. We train to repress it by calling it impolite, a gaffe, a misconduct of affect. Collecting pictures of the disabled is a kind of gaffe itself; Żmijewski’s curiosity may be excused by the fact that he is an artist and a persistent pedagogue.

Often Żmijewski uses spotlight to create a sort of amateur shadow-theatre or puppet-show. Sometimes it looks like people are rehearsing very elaborate choreography.

This uncanny drive reminds of Eadweard Muybridge, another collector of moving bodies, as well as obsessive inventor, researcher, and pioneer. He produced something over 100,000 moving images of animals and humans, captured by special cameras. A curious fact: in 1860, following a violent accident and severe head injury, Muybridge underwent advanced treatment of symptoms like double vision, confused thinking, impaired sense of taste and smell, etc. There is a speculation that it was this limit bodily experience that made him so interested in the body, and so creative and brave about pursuing his inventive and collecting drive, reaching beyond the conventions of seeing and the social conventions alike.

Żmijewski is patiently studying sequences of failures and faux pas: a young woman with crutches, escorted by the artist, climbing stairs with him, going to the river (she smiles to the camera), people struggling to walk up and down the stairs, to sit and stand up. They stumble and sway, move forward and backward, clumsy and awkward. The protagonists are filmed in various locales and settings: staircases, ballet room, on wooden floors, by windowsills. The fact that these movements are not accompanied by a single sound defamiliarizes the experience even more. Often Żmijewski uses spotlight to create a sort of amateur shadow-theatre or puppet-show. Sometimes it looks like these people are rehearsing very elaborate choreography. Sometimes it looks like they are dancing, when attempting to change position. Something we unconsciously do all the time for them turns into a very complicated process extended in time. The “as if” recurs and haunts… as if they were drunk, as if they were acting, as if they were fooling around. And suddenly all we know about our relationship with the body is questioned. Take Merleau-Ponty as an example, concept of the body re-read and re-written on so many occasions.

Our body is not in space like things; it inhabits or haunts space. It applies itself to space like a hand to an instrument, and when we wish to move about we do not move the body as we move an object. We transport it without instruments as if by magic, since it is ours and because through it we have direct access to space. For us the body is much more than an instrument or means; it is our expression in the world, the visible form of our intentions. Even our most secret affective movements, those most deeply tied to the humoral infrastructure, help to shape our perception of things.[8]

Body art, poststructural and posthuman theories of the subject as well as disability studies have proved how problematic if not false this conception seems. The disabled person’s moving body is experienced and seen as an object, an obstacle to a subject. Or is it not the body?

Who are “we” from the above fragment. The resistant bodies from Żmijewski’s collection, the wilful body parts and the incredible filmic portraits call for a more inclusive sense of difference: what it is and what it requires. This extensive collection has a potential to overturn the structure of collective: the “we” who move “as if by magic.” The magic Żmijewski uses guides him in most obscure of territories. He is not afraid to fail, and failure makes a lot of sense in the ablest world, the world where only winners win and losers lose. He experiments and fails, and experiments again for the sake of expanding the field of vision and the field of empathy. It is not to say that when he fails, he wins; it is to say, that failure and success need to be reconsidered for us all to move and be moved for real.

Text ”Żmijevski’s uneducation” by Katarzyna Bojarska was published in Blindspots. Artur Żmijewski. Exhibition catalogue, Association Latvia Cultural Projects, Riga, 2017, p. 9–13.

* The title refers to documenta 14, but also to the tradition of artistic and social pedagogical which grew from Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, including Oskar Hansen, Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz, Grzegorz Kowalski. I consider Żmijewski an important part of this tradition, devoted to a program of social pedagogy realised by the means of visual arts.

[1] Lennard J. Davies, Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness and the Body. (New York: Verso, 1995) 5.

[2] See: Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

[3] Davies, xii.

[4] Ibidem, 12.

[5] Vito Acconci, “Notes on Work 1967-1980”, in his Writing, Work. Projects, ed G. Maure (Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa, 2001), 350-51.

[6] Michael Taussig, Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses. (New York: Routledge, 1993), xvi.

[7] Second, Deaf Bach (2002), was shot in St. Thomas Church in Leipzig; children sang Bach’s cantata Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben.

[8] A text by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, published posthumously in 1962, in The Primacy of Perception, ed. J. M. Edie Evanston, Northwestern University Press, 1964, p. 5. Cited in Christine Poggi, Following Acconci / Targeting Vision, Performing the Body / Performing the Text, ed. A. Jones. (New York: Routledge, 1999), 239.

LV

Tā vietā, lai skatītos uz šo nenogludināto tēlu, kritiķis pievēršas seksualitātes šķidrumiem, lubrikanta mirdzumam, ķermeņa kā teksta glosārijam, interteksta heteroglosijai, šizofrēniķa glosolālijai. Taču gandrīz nekad ‒ citādi spējīga cilvēka ķermenim.[1]

Šāds skats: kails mākslinieks sēž zemē sakrustotām kājām un aicinoši izpleš rokas, gatavs ciešam kontaktam ‒ kontaktam ar Citu ‒ un iespējamām briesmām, kas šo Citu var piemeklēt. Pirms tam kadrā bija redzami kaili cilvēki, kas palēninātā kustībā skraidīja apkārt, ietriecoties cits citā. Šī darba nosaukums ir “Es un AIDS” (Ja i AIDS, 1996), un šobrīd, kad pagājis vairāk nekā 20 gadu, kaut arī AIDS vairs nav tik liels drauds, filma joprojām liekas ļoti aktuāla. Kad es domāju par Žmijevski, es viņu iztēlojos kā šo kailo cilvēku, kura atsegtais “es” uzaicina un saņem neskaitāmus stimulus, drīzāk neviennozīmīgus nekā sāpīgus, un pēc tam saskaņā ar paša noteikto iesaistīšanās procedūru tos pārtulko attēlos ‒ klejojot starp dažādiem diskursa līmeņiem, turoties nomaļus no saskatāmā, pieņemamā un piedienīgā.

Laikā, kad Rietumu humanitārajā jomā aizsākās invaliditātes pētniecības kā atsevišķas un neatkarīgas disciplīnas veidošanās un attīstīšanās, Žmijevskis sāka veidot savus darbus nevis par, bet gan ar invalīdiem. Abām aktivitātēm, gan akadēmiskajai izpētei, gan mākslinieciskajai praksei, šķiet, pamatā likta vienāda pārliecība, proti, ka invaliditātes vieta ir minoritāšu diskursā. Gandrīz paralēli viena otrai tās kritizējušas diskriminējošus naratīvus un norādījušas uz iespējamiem emancipējošiem risinājumiem. Šajā jaunajā kontekstā invalīdu pieredze kļuvusi analoga ar situāciju, ar kādu sastopas sievietes, cilvēki ar citu ādas krāsu, neheteroseksuāļi un kvīri (queers). Žmijevska sociāli izmantotie mākslinieciskie centieni vērsti uz cīņu ar neredzamajām zonām citādā ziņā visai pašpārliecinātās vērotāju kopienas redzes laukā. Viņš rūpīgi un metodiski pēta izslēgšanas momentus un kritiski aplūko iekļaušanas noteikumus, piedāvājot telpu, kurā dažādās formās var izpausties līdz šim sabiedrības acīs nevēlami subjekti, tādi kā cilvēki, kuru spējas ir kaut kādā veidā ierobežotas.

Žmijevska uzstājīgā vēlēšanās skatīties uz citādi spējīgajiem ir tikpat lielā mērā politisks kā māksliniecisks projekts, kura varā ir pārveidot vizualitātes likumus.

Pirmā mācību stunda. Ķermenis

Domājot par pēdējiem trim gadu desmitiem, varētu apgalvot, ka ķermenis (ar visiem saviem defektiem un slimībām) kļuvis par nožēlojamu Citu, kas, no vienas puses, mūžam atgādina par sevi ķermeņa mākslā, performancē un videomākslā ‒ gan teorijā, gan praksē ‒ un Polijas politisko un sociālo pārvērtību vēsturē pēc 1989. gada, no otras puses. Žmijevska uzstājīgā vēlēšanās skatīties uz citādi spējīgajiem ir tikpat lielā mērā politisks kā māksliniecisks projekts, kura varā ir pārveidot vizualitātes likumus. Mākslinieks piesaka savas “tiesības skatīties” un ar šādu rīcību atsaucas uz dažādu redzes režīmu vēsturi un šībrīža situāciju[2] ‒ tieši tāpat, kā to darīja Diāna Arbusa (Diane Arbus), Rodžers Balens (Roger Ballen), Ričards Bilingems (Richard Billingham), Boriss Mihailovs (Boris Mikhailov), Hanna Vilke (Hannah Wilke), Katažina Kozira (Katarzyna Kozyra), Alina Šapožņikova (Alina Szapocznikow), Davids Vojnarovičs (David Wojnarowicz), Felikss Gonsaless-Torress (Felix Gonzalez-Torres), Dereks Džārmens (Derek Jarman) un Džo Spensa (Jo Spence), katrs savā laikā un pēc saviem noteikumiem.

Šajā sociālās pedagoģijas projektā mēs pievēršamies problemātiskam ķermenim ‒ ķermenim ar problēmām un ķermenim, kas sagādā problēmas, liekot apstrīdēt normativitātes struktūru. Runājot Lenarda Deivisa vārdiem, Žmijevskis palīdz normāliem cilvēkiem “saskatīt pēdiņas, kurās liekams viņu priekšstats par savu normalitāti”[3] un pēta invaliditāti kā sociālu, vēsturisku un kulturālu konstruktu. Tam, kādas ir mūsu jūtas un domas par ķermeni (tāpat kā ķermenī), ir visai maz sakara ar spontanitāti, toties tas ļoti lielā mērā saistīts ar “iegrožošanas ideoloģiju” un “kontroles politiku”. Tieši tas pats sakāms par to, kā veidojas atšķirīga pieeja ķermeņiem ar pilnām vai ierobežotām spējām, tam, kas tiek uztverts kā atkāpe un kas ‒ jau kā novirze, vai tam, kurā brīdī nespēja veikt zināmas darbības vai funkcijas kļūst par trūkumu, par defektu, par acīmredzamu atšķirību, kas liekas uzkrītoša un satrauc. Invaliditāte, nespējība, kā norāda Deiviss, ir spoguļmoments[4], kam bieži seko jautājums, vai ķermeņi ar šo “ne-” ir cienīgi tikt padarīti redzami (un kādos kontekstos); tas savukārt ir turpinājums Džūditas Batleres (Judith Butler) un citu uzdotajam jautājumam, kuras dzīves ir cienīgas tikt izdzīvotas un apraudātas. Un tomēr varētu rasties jautājums, kādi ir apstākļi, kuros ķermenis ar pilnām spējām kļūst par ķermeni, kas ir nespējīgs. Šis “ne-” ir trūkuma zīme eiblisma pasaulē ‒ pasaulē, kurā noteicošais ir baudu izjušana un mērķu sasniegšana. Kolektīvais “normālais” ķermenis, “normālā” kolektīva ķermenis daudzkārt demonstrējis, ka jebkāda novirze no normas tiks kaunināta kā trūkums ‒ trūkums, kas var nozīmēt dažādas lietas, to skaitā estētisku defektu: ķermenis ar nepilnīgām spējām neizskatās labi, tas neliek sevi iekārot. Tas nav skaists, un pat reizēs, kad tas tāds tomēr ir, līdzi vienmēr nāk obligāts “bet”, piemēram: gudrs, bet invalīds, ‒ vai: invalīds, bet gudrs. Cik ērti un mierinoši. Tu tiksi pieņemts tikai tad, ja pieliksi pūles: mēģini izārstēties, mēģini kļūt labāks, lai būtu tāds, kāds esmu es, ‒ lai man nevajadzētu justies neērti tava svešāduma dēļ, lai man nevajadzētu tikt interpelētam, lai es nejustu, ka esmu tev vajadzīgs, lai es nejustu, ka tu esi vajadzīgs man, lai es justos labi.

Otrā mācību stunda. Mīli savu tuvāko

Ap invalīda ķermeni koncentrējas vesels afektu spektrs – no pretīguma, riebuma un bailēm līdz empātijai un žēlumam. Žmijevskis, šķiet, izmēģina tos visus, neizlaižot nevienu pašu. Un tomēr viņš pārvar pretīgumu; viņa darbos ķermeņi ar fiziskiem defektiem, slimi ķermeņi kļūst par draugiem; tie kļūst aizskarami un mīlami ‒ kļūst par sabiedrotajiem un pienākuma objektiem. Mīlestība pret ķermeni ar fiziskām nepilnībām vai slimu ķermeni realizējas caur kameru, nekad pārāk tiešā veidā. Darbā “Acs pret aci” (Oko za Oko, 1998) mākslinieks inscenē fiziski pilnīgu un nepilnīgu ķermeņu satikšanos. To uzdevums ir izpildīt dažādus uzdevumus (reizēm tik elementārus kā staigāšana vai kāpšana pa kāpnēm), kas izvirza priekšplānā abu veidu ķermeņu atšķirības un to savstarpējo atkarību. Ķermeņi ir kaili, neaizsargāti, reizēm groteski. Žmijevskis aplūko savstarpējās sasaistes un pazemojuma robežas.

Vai “normālu cilvēku” un “invalīdu” kailums vai intimitāte liek justies neērti? Vai šie smiekli ir aizliegti?

Viņš apgāž Vecās Derības saucienu pēc atriebības. Mākslinieks nepieprasa līdzvērtīgu zaudējumu (acs pret aci); viņš parāda, kā nostāties otra vietā, aizstāt un salabot ‒ nevis ar operācijas, bet gan atbalsta un empātijas palīdzību: vesels loceklis trūkstošā vietā. Kaili vīriešu ķermeņi noplukuša izskata interjeros kopā guļ, kopā staigā, kopā lec… “Normālie” piedāvā savas rokas vai kājas tiem otriem trūkstošo vietā. Šī ķermeņu brālība veido groteskus hibrīdus, kas dzied tautasdziesmas un izpilda absurdas horeogrāfiskas pasāžas, it kā Žmijevskis darītu visu iespējamo, lai distancētos no žēluma vai pašslavināšanās kārdinājuma. Tas mazliet sasaucas ar ceļojošā cirka ērmu šovu, tomēr pašos pamatos ir pilnīgi citādi. Un netrūkst arī dušas ainas, kas var kļūt par prelūdiju noziegumam vai mīlestībai. Jaunas sievietes rokas kalpo vīrietim, lai viņš varētu ieziepēties un nomazgāties. Tā ir ārkārtīgi aizkustinoša žestu virkne, kas parāda vienu nesavtīgu būtni, kura pakalpo otrai. Sadošanās rokās nekad nav nozīmējusi tik daudz.

Vai tas ir neglīti? Vai tas ir bezgaumīgi vai nekaunīgi? Vai “normālu cilvēku” un “invalīdu” kailums vai intimitāte liek justies neērti? Vai šie smiekli ir aizliegti? Vai varbūt skatītājam vajadzētu atmest visu iepriekš minēto un just / domāt par kaut ko citu, kaut ko ārpus sevis paša? Mēģinot iedziļināties “Acs pret aci” kontekstā, es gluži nejauši uzdūros citam mākslas darbam, kas apspēlē aizvietojumus un savstarpēju sasaisti, tiesa gan ‒ pilnīgi citā kontekstā. Piezīmēs par savu “Sekojošo darbu” (Following Piece, 1969) Vito Akonči (Vito Acconci) rakstīja:

Papildinātājattiecības ‒ es pievienoju sevi citam cilvēkam ‒ es ļauju, ka man atņem kontroli ‒ es esmu atkarīgs no cita cilvēka ‒ viņš man ir vajadzīgs, es neesmu vajadzīgs viņam ‒ subjektīvas attiecības. Es ieņemu atvēlēto vietu sistēmā ‒ mani var aizstāt ‒ šeit nozīme vērtībai, kas piemīt manai vietai, nevis manām individuālajām īpatnībām.[5]

Atrasties telpā, aizņemt un apdzīvot sociālas telpas, kustēties un tikt kustinātam, sekot un ļaut, ka seko tev, bet visvairāk ‒ iziet no sevis un nonākt sasaistē, tas viss Žmijevska darbā nozīmē ļoti daudz. Ķermeņi, ko viņš rāda, ir sociāli un estētiski marginalizēti vai atstumti, taču viņš atved tos atpakaļ ‒ ne jau lai tie tiktu aplūkoti, bet lai tie būtu klāt, lai kļūtu piederīgi, iekļauti un “saskarē” ar mums, vienalga, cik “normāli” mēs būtu.

Trešā mācību stunda. Deformācijas formas

Ja dzīve ir konstruēta, kā tas var būt, ka tā liekas tik nemainīga?

Kāpēc kultūra liekas tik dabiska?[6]

2001. gadā Žmijevskis uzņēma pirmo daļu no savas “Dziedāšanas stundas” (Lekcja śpiewu)[7], sarīkojot Varšavas Evaņģēliskajā Augsburgas konfesijas Svētās Trīsvienības baznīcā Jana Maklakeviča (Jan Maklakiewicz, 1899–1954) “Poļu mesas” Kyrie atskaņojumu; to ērģeļu pavadījumā izpildīja nedzirdīgu pusaudžu koris. Mēs redzam šos jaunos ļaudis ar prieku gatavojamies koncertam un izpildām kaut ko, par ko viņiem zināms (pareizāk ‒ par ko viņiem stāstīts), ka tas ir mākslas darbs; mēs dzirdam vājprātīgu skaņu, spiedzienu, gaudu un kaucienu kakofoniju. Redzot, cik brīvi viņi uztver visu šo pasākumu, nedaudz mazinās arī mans stress. Kam šī ir dziedāšanas stunda? Kā formulēt, kas notiek šajā video? Vai ir labi apbrīnot viņu “dziedāšanu”? Kādas kategorijas un kritērijus lietot vērtēšanas vietā? Mākslinieks palīdz ar savu komentāru par šo darbu:

“Dziedāšanas stunda” nav par vājākā atļaušanos pārkāpt robežas. Viņu priekšnesuma rezultāts nav labs ‒ dziedāšana ir un paliek sakropļota, deformēta. Šis video ir par neizdošanos. (..) Kurlo dziedātāju piedalīšanos “Dziedāšanas stundā” vajadzētu interpretēt kā atteikšanos izpatikt dzirdīgajiem un kā mēģinājumu būvēt pašiem savas hierarhijas, to skaitā ‒ estētiskas.

Dziedātāji nepakļaujas “spējīgo teroram”, un spējīgajiem tiek atvēlēta telpa, kurā saskatīt un atzīt dominējošās formas teroru ‒ to, kas valda gan dzīvē, gan mākslā. Ja cilvēkam šķiet, ka kurlmēma cilvēka dziedāšana ir “absurda”, viņa reakcija iekļaujas šī terora loģikā; tās ir šaubas par to, vai tiem, kuru pašizpausme šķiet “nepareiza” vai pat šī vārda necienīga, vispār ir tiesības sevi izpaust. Žmijevska sētais apjukums atbrīvo jaunu telpu, kurā iespējams at-izglītoties, noskaņot savu uztveri citu ķermeņa modalitāšu skaņām ‒ modalitāšu, nevis defektu.

Desmit gadus vēlāk mākslinieks uzņem darbu “Akli” (Na ślepo, 2010); filmā viņš ir kopā ar neredzīgiem cilvēkiem, kuri glezno to, ko viņš palūdzis: pašportretu, ainavu, dzīvnieku. Daži no dalībniekiem ir neredzīgi kopš dzimšanas, citi zaudējuši redzi nelaimes gadījumā. Viņu sarunas skatītājam sniedz satriecošus atklāsmes brīžus: “Es to redzu tā – šī ir ainava no manas galvas.” – “Vai tur nekā netrūkst?” Žmijevskis vaicā vienam no saviem gleznotājiem. “Trūkst. Redzes,” šis cilvēks izaicinoši atbild (it kā norādot, ka Žmijevska darba pamatā ir absurda vai cietsirdīga ideja, taču neatsakoties tajā piedalīties). “Man jāuzzīmē acis,” saka sieviete, kura glezno portretu. “Man pašai tādas nekaitētu,” viņa pēc brīža piebilst. Vērojot, kā viņi glezno, un klausoties, kā viņi sarunājas, skatītājs sajūt vēl vienu emocionālu dūrienu: tu saproti, ka starpība starp tiem, kuri redz, un tiem, kuri neredz, izpaužas arī tajā, kā kustas ķermenis, ‒ šo cilvēku dzīves horeogrāfija atšķiras tikpat lielā mērā kā viņu vizuālais priekšstats par pasauli.

Aklumam un mākslai ir senas attiecības. Aklums ir būtiska Rietumu mākslas metafora; par to daudz un plaši rakstīts. Un, lai gan tas ir tik nozīmīgs faktors, tomēr reti pārstāvēts kā reāla, materiāla neredzīgo pieredze. Aklu cilvēku izpratni, gudrību, iztēli un atmiņu nepieciešams piejaucēt ar zināšanām, ko viņiem piedāvā kultūra, ‒ lai viņi zinātu, kā lietas izskatās, lai mums nevajadzētu uztraukties par to, ko viņi redz, kad neredz. Vēl viena neizdošanās: gleznas ir sliktas, naivas, bērnišķīgas, vājas vai arī visai Saja Tvomblija (Cy Twombly )garā ‒ interesantas, provocējošas… Un, lai kā mēs censtos, mums tik un tā neizdodas piekļūt tam, ko viņi tik tiešām neredz, ‒ tikai tam, kā mēs viņiem esam iemācījuši sajust, ka viņi vēlētos redzēt to, ko redzam mēs.

Ceturtā mācību stunda. Kustības ar tēliem

Superkroplis (supercrip) invaliditātes pētniecībā ir pilnīgi leģitīms vārds, ar ko apzīmē cilvēku, kurš gan ir invalīds, bet kaut kādā jomā apveltīts ar spožu talantu vai arī cilvēks, kurš ir invalīds un smagi strādā, lai pārvarētu savu nespējību. Savā “Kolekcijā” (Kolekcja, 2010‒2016) Žmijevskis atgriežas pie mēmā kino tradīcijas un laikiem, kad smiešanās par ķermeņa nespēju piederēja pie populārās kultūras tāpat kā uzjautrināšanās par cilvēkiem ar fiziskiem defektiem. 19. gadsimta beigās un 20. gadsimta pirmajā desmitgadē tapa neskaitāmas brutāli humoristiskas īsfilmas par “bezkājainiem skrējējiem”. Mākslinieka savāktais un piedāvātais mēmu melnbalto video īsfilmu krājums demonstrē dažādus kroplīgu cilvēka kustību vai kroplīgā kustībā esošu cilvēka ķermeņa piemērus, vienalga, vai deformācijas cēlonis ir multiplā skleroze, bērnu trieka, Hantingtona slimība vai kāda cita problēma. Žmijevskis no jauna atgriežas arī pie šīs infantilās fascinācijas ar atšķirīgo, šī tīksmīgo satraukuma trīsu un baiļu sajaukuma, kas izpaužas blenšanā, tieksmē pārāk ilgi nenovērst skatienu, ko mēs mācāmies apspiest, saucot to par nepieklājību, nepiedienīgu izlēcienu, nepieņemamu savas reakcijas izrādīšanu. Paziņot, ka tu kolekcionē invalīdu attēlus, jau pats par sevi ir izlēciens; šo nepiedienīgo ziņkārību mobilizē un attaisno fakts, ka Žmijevskis ir mākslinieks un konsekvents pedagogs.

Bieži Žmijevskis izmanto prožektora gaismas, lai radītu kaut ko līdzīgu amatieru ēnu teātrim vai marionešu izrādei. Reizēm šīs kustības izskatās kā ārkārtīgi sarežģīti horeogrāfiski vingrinājumi.

Šī dīvainā dziņa atsauc atmiņā kādu citu ķermeņa kustību kolekcionāru – Edvardu Maibridžu (Eadweard Muybridge), fanātisku izgudrotāju, pētnieku, celmlauzi. Viņš savulaik uzņēma vairāk nekā 100 000 kustībā esošu dzīvnieku un cilvēku attēlu, ar fotoaparāta palīdzību fiksējot to, ko cilvēka acs nespēj izšķirt kā atsevišķas kustības. Interesants fakts: 1860. gadā pēc smagā nelaimes gadījumā gūtas nopietnas galvas traumas Maibridžs ilgstoši ārstējās, lai atbrīvotos no sekojošajiem simptomiem: redzes dubultošanās, juceklīgas domāšanas, taustes un ožas traucējumiem utt. Pastāv viedoklis, ka tieši šie fizisko spēju ierobežojumi likuši viņam tā ieinteresēties par cilvēka ķermeni un pamudinājuši tik radoši un drosmīgi ļauties savai izgudrošanas un kolekcionēšanas dziņai, sniedzoties tālu aiz robežām, ko novelk cilvēka redzes iespējas un vispārpieņemtās sociālās normas.

Žmijevskis pacietīgi izseko dažādu neveiksmju un neveiklību virknēm: jauna sieviete uz kruķiem mākslinieka pavadībā kāpj pa kāpnēm, dodas uz upi (viņa uzsmaida kamerai); cilvēki ar lielu piepūli kāpj augšā un lejā pa kāpnēm, apsēžas vai pieceļas. Viņi klūp un grīļojas, virzās uz priekšu un kāpjas atpakaļ ‒ neveikli un lempīgi. Mākslinieks savus varoņus filmē dažādās vietās un vidēs, piemēram, uz kāpnēm, baleta zālē, uz koka grīdām, pie palodzēm. Fakts, ka šīs kustības nepavada neviena skaņa, padara šo pārdzīvojumu vēl neatpazīstamāku. Bieži Žmijevskis izmanto prožektora gaismas, lai radītu kaut ko līdzīgu amatieru ēnu teātrim vai marionešu izrādei. Reizēm šīs kustības izskatās kā ārkārtīgi sarežģīti horeogrāfiski vingrinājumi. Kad mēģinājums mainīt pozu ‒ kustība, ko parasts cilvēks atkārto miljoniem reižu un pilnīgi neapzināti, ‒ kļūst par ārkārtīgi sarežģītu laikā izvērstu procesu, izskatās, it kā viņi dejotu. Šis “it kā” atkārtojas un uzstājīgi neatkāpjas… it kā viņi būtu piedzērušies, it kā viņi tēlotu, it kā viņi ākstītos. Un piepeši mēs vairs neesam droši ne par ko no tā visa, ko zinām par savām attiecībām ar ķermeni. Piemēra pēc palūkosimies kaut vai uz to, ko teicis Moriss Merlo-Pontī (Maurice Merleau-Ponty), kura skats uz ķermeni no jauna interpretēts un pārrakstīts jau tik daudz reižu:

Mūsu ķermenis neeksistē telpā kā priekšmeti; tas apdzīvo telpu vai uzturas tajā. Tas iedarbojas uz telpu kā roka uz instrumentu, un, kad mēs vēlamies pārvietoties, tad nekustinām ķermeni tādā izpratnē, kā pārvietojam kādu objektu. Mēs to transportējam bez kādu rīku palīdzības, it kā ar burvju varu ‒ tāpēc ka tas ir mūsu un caur to mums ir tieša piekļuve telpai. Ķermenis mums ir kaut kas daudz vairāk nekā rīks vai līdzeklis; tā ir mūsu izpausme telpā, mūsu nolūku redzamā forma. Pat mūsu slēptākās afektīvās kustības, tās, kuras visdziļākajā līmenī saistītas ar humorālo infrastruktūru, palīdz veidot mūsu uztveri.[8]

Ķermeņa māksla, poststrukturālisma un posthumānisma teorijas šajā jautājumā, kā arī invaliditātes pētniecība pierādījušas, cik problemātisks, lai neteiktu ‒ aplams, ir šis priekšstats. Ķermenis invalīda kustībās tiek izjusts un uztverts kā objekts, kā šķērslis, ar ko jāsaduras subjektam. Vai varbūt tas nav ķermenis?

Kas ir šie “mēs” no iepriekš citētā fragmenta? Žmijevska kolekcijas nepakļāvīgie ķermeņi, gribas pilnās ķermeņa daļas un fantastiskie kinoportreti, ko viņš palaikam nolemj iekļaut savā darbā, prasa kādu plašāku izpratni par to, kāda ir atšķirība un kādas prasības tā izvirza. Šī kolekcija, kas turpina augt, potenciāli varētu sagraut kolektīvā struktūru ‒ šos “mēs”, kuri kustas “it kā ar burvju varu”. Žmijevska burvju vara aizved viņu uz pašām slēptākajām no teritorijām. Viņš nebaidās piedzīvot sakāvi, un sakāvei ir liela nozīme eiblisma pasaulē ‒ pasaulē, kur uzvar tikai uzvarētāji, bet zaudētāji ‒ zaudē. Viņš eksperimentē un cieš neveiksmi, un eksperimentē atkal ‒ redzes un empātijas lauka paplašināšanas vārdā. Tas nenozīmē, ka viņš patiesībā uzvar, kad cieš neveiksmi; tas nozīmē, ka nepieciešams pārskatīt mūsu neveiksmes un panākumu izpratni, lai mēs visi patiešām varētu kustēties un tikt (aiz)kustināti.

Katažinas Bojarskas teksts „Žmijevska at-izglītošanās” ir publicēts izdevumā „Neredzamās zonas. Artūrs Žmijevskis. Izstādes katalogs”. Biedrība Latvijas Kultūras projekti. Rīga, 2017. 4.-8.lpp.

[1] Davies, Lennard J. Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness and the Body. New York: Verso, 1995, p. 5.

[2] Sk.: Mirzoeff, Nicholas. The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

[3] Davies, Lennard J. Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness and the Body, p. xii.

[4] Turpat, 12. lpp.

[5] Acconci, Vito. Notes on Work 1967–1980. In: Acconci: Writing, Work. Projects. Ed by Gloria Maure. Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa, 2001, p. 350–351.

[6] Taussig, Michael. Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses. New York: Routledge, 1993, p. xii.

[7] Otrā daļa“Kurlais Bahs” (2002) tika uzņemta Sv. Toma baznīcā Leipcigā; bērni dziedāja Baha kantāti Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben.

[8] Morisa Merlo-Pontī dzīves laikā nepublicēts teksts. Pirmpublicējums: Revue de métaphysique et de morale, 1962, Nr. 4, p. 401‒409.

Przypisy

Stopka

- Osoby artystyczne

- Artur Żmijewski

- Wystawa

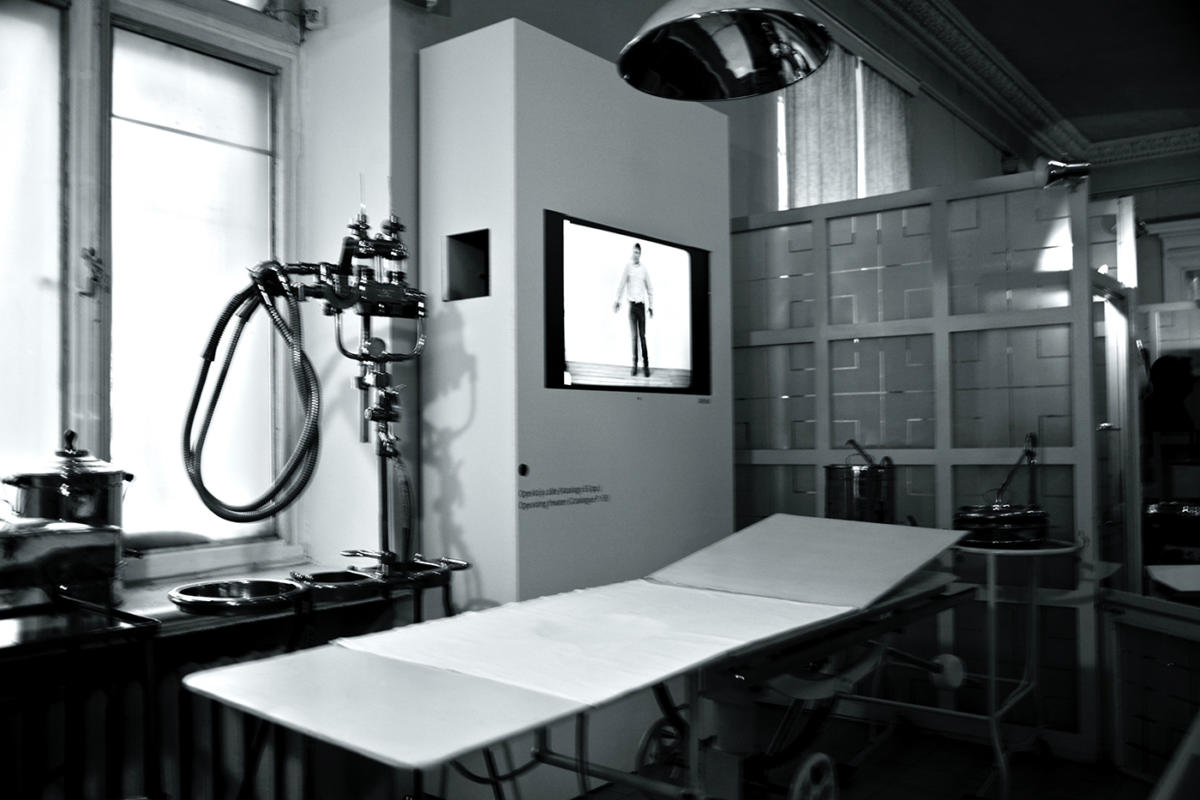

- Blindspots / Neredzamās zonas

- Miejsce

- Pauls Stradiņš Museum of the History of Medicine / Paula Stradiņa Medicīnas vēstures muzejā

- Czas trwania

- 3.06–24.09.2017

- Fotografie

- Ilze Kuisele

- Strona internetowa

- mvm.lv