Uchodźca w galerii / A refugee in a gallery

PL

W najnowszym spocie promującym Narodową Galerię w Pradze obserwujemy w zwolnionym tempie stopy kilku osób podziwiających wystawę. Obuwie wskazuje na charakter zwiedzających: glany, żółte trampki, dziecięce buciki. W przypływie zachwytu każdy z nich upuszcza swoje insygnia: zakonnica różaniec, dziecko misia, żołnierz menażkę, a młoda dziewczyna słuchawki. To jednak nie wszystko: wśród zwiedzających jest także bosy uchodźca, któremu z ręki wypada jeszcze mokra kamizelka ratunkowa. Męski głos zza kadru anonsuje wystawy wielkich nazwisk: Gerharda Richtera, Magdaleny Jetelovej i Ai Weiweia.

W Pradze, jak i w całych Czechach, uchodźców praktycznie nie ma. Zgodnie z europejskimi ustaleniami, kraj powinien przyjąć 1600 osób. Przyjął 12. W lutym zeszłego roku kilka tysięcy osób demonstrowało w Pradze przeciwko otwieraniu granic i „islamizacji Europy”[1]. Kilka godzin później kilku zamaskowanych mężczyzn zaatakowało autonomiczne centrum kultury Klinika zaangażowane w pomoc uchodźcom[2].

Choć nie widać ich na ulicach, uchodźcy są mocno reprezentowani w czeskiej sztuce – poza Národní galerie, pojawiają się także na zaangażowanej Universal Hospitality 2 w MeetFactory, poświęconej krytycznej refleksji nad środkowoeuropejską (nie)gościnnością.

Narodowa Galeria dumnie zaprasza na pierwszą indywidualną wystawę chińskiego artysty w Czechach oraz Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej.

Národní galerie ma za sobą trudne lata rządów Milana Knížáka, artysty związanego z Fluxusem, który był dyrektorem tej placówki przez ponad dekadę (1999-2011). Knížák zamienił galerię w swój prywatny folwark, co sprawiło, że dla czeskiego środowiska artystycznego długo nie była ona jakimkolwiek punktem odniesienia w dyskusji o sztuce współczesnej. Od 2014 roku kieruje nią Jiří Fajt i chociaż poprawa jest zdecydowana (Galeria stała się bardziej przyjazna, widoczna na arenie międzynarodowej i próbuje przyciągać coraz to nową publiczność) to wielkiego entuzjazmu wobec obecnego programu w środowisku raczej nie słychać. Opiera się on na blockbusterach i znanych nazwiskach, jak na przykład obecnie: w kilku filiach galerii odbywają się jednocześnie wystawy artystów reprezentujących najwyższą ligę czeską, niemiecką i chińską. To właśnie ta ostatnia zbiera najbardziej skrajne opinie oraz skupia krytykę, która dotyczy całej instytucji pod przewodnictwem Jiříego Fajta: gwiazdy, drogie bilety i niewiele poza tym (no, może poza popularną muzealną kawiarnią).

Wystawa Law of the Journey Ai Weiweia eksponowana jest w monumentalnych wnętrzach byłego Pałacu Targowego (Veletržni). Narodowa Galeria dumnie zaprasza na pierwszą indywidualną wystawę chińskiego artysty w Czechach oraz Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej. W kilku salach rozlokowano pochodzące z ostatnich dziesięciu lat realizacje artysty. Wszystkie traktują o potwornej polityce i ludzkiej krzywdzie, wszystkie mają świadczyć o tym, jak mocno Ai Weiwei zaangażowany jest w palące światowe problemy.

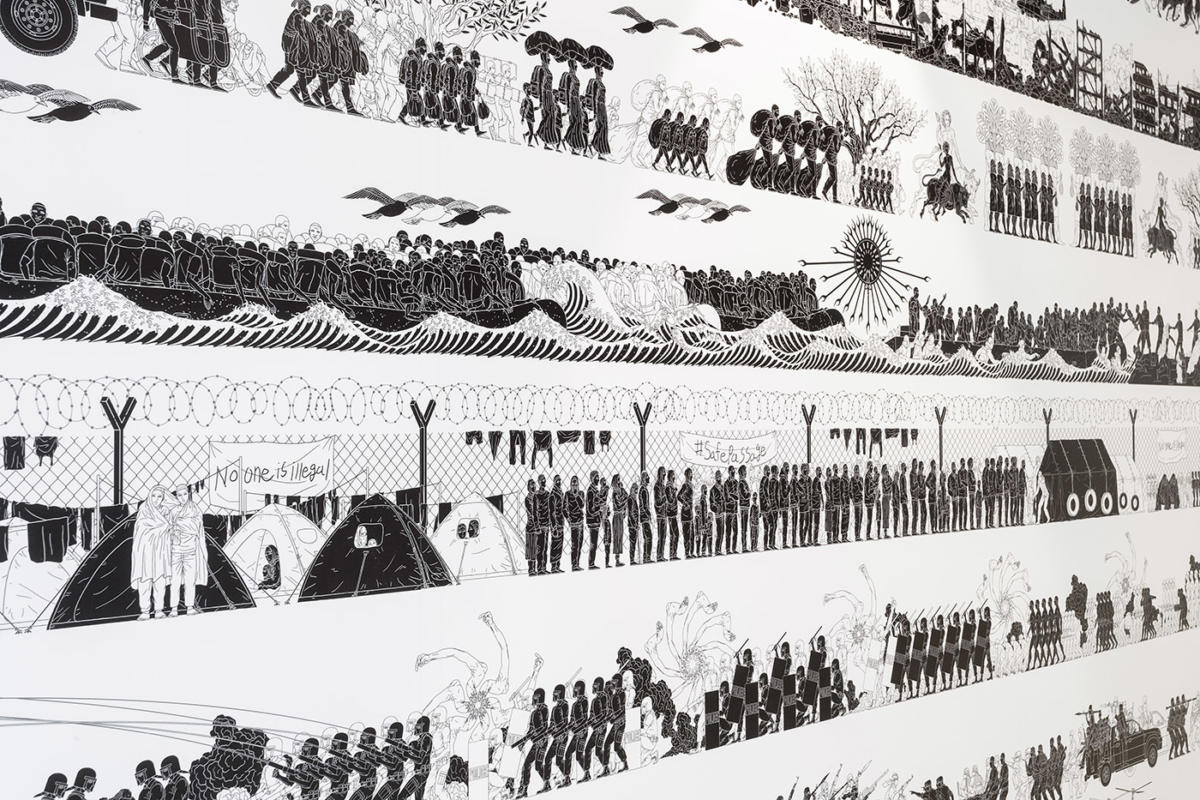

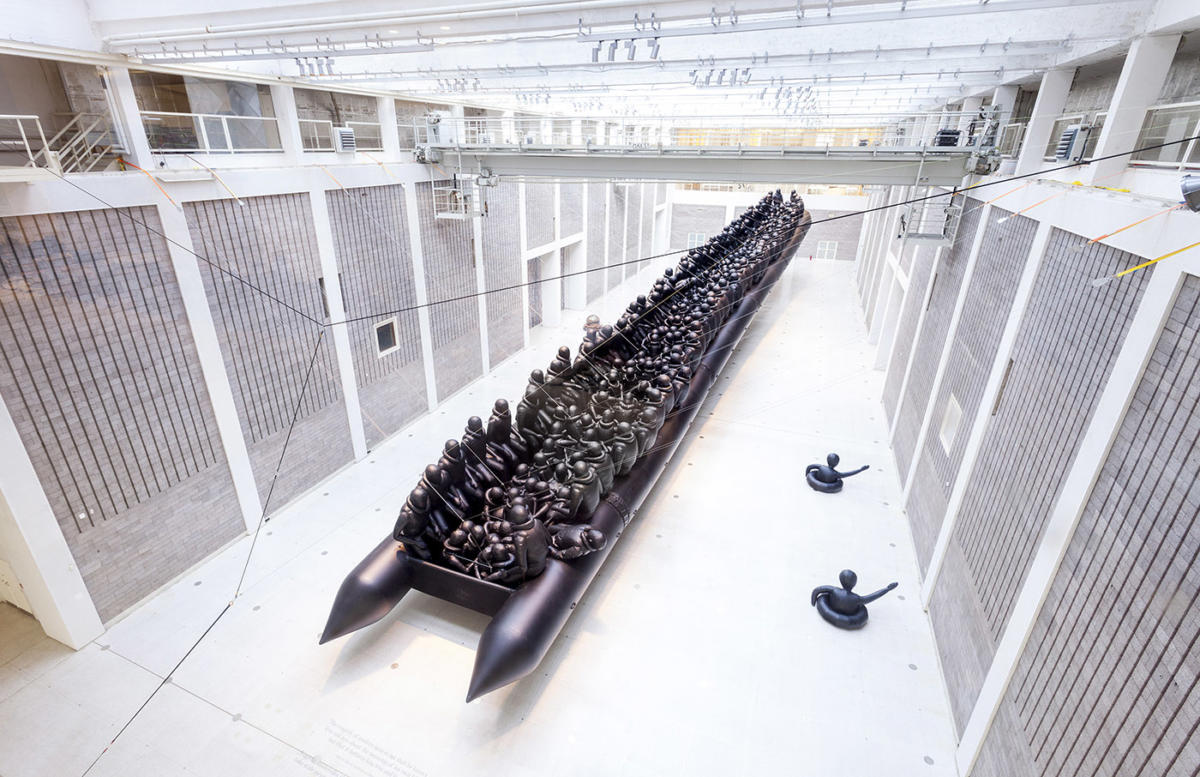

Pod sufitem hallu muzeum zawieszono gigantycznego węża. Wykonany jest ze szkolnych tornistrów – każdy z nich reprezentuje jednego z uczniów, którzy zginęli podczas trzęsienia ziemi w chińskiej prowincji Sichuan w 2008. Na ścianach korytarza prowadzącego do głównej sali wystawowej rozmieszczone są poziomo czarno-białe sceny z życia uchodźcy: ucieczki, wędrówki, koczowanie w namiotach z drutami kolczastymi w tle. Najważniejszy jest tu jednak kolosalny ponton unoszący się nad ziemią – wielki, ciemny, przepełniony anonimowymi postaciami, przytłaczający nas zaraz po wejściu do ogromnej hali. Pod nim, na podłodze, wypisano szereg cytatów odnoszących się zarówno do aktualnej sytuacji w Syrii (Samar Yazbek), jak i ogólnej kondycji ludzkiej czy praw człowieka (Václav Havel).

Ściany wytapetowane selfie artysty i śmierdzący gumą ponton unoszący się nad cytatami ze światowej literatury mogą wywołać podziw, ale także wielkie zdziwienie.

Nie bez znaczenia dla tematu wystawy – podróży i tułaczki – jest sama lokalizacja galerii. W latach 1939-1941 modernistyczny pałac służył jako punkt zbiórki dla czeskich Żydów wysyłanych stamtąd m.in. do łódzkiego getta. Pamięć o tych wydarzeniach odsyła do genezy dzisiejszych fobii społeczeństw Europy Środkowej, nastawionych złowrogo do uchodźców. Jakkolwiek brutalnie to zabrzmi, dzisiejsze wspólnoty Czech, Polski czy Węgier są tak homogeniczne jak są dzięki wojennej eksterminacji oraz późniejszym migracjom do Izraela.

Na bocznych ścianach monumentalnej sali oglądać można fotograficzny pamiętnik z podróży Ai Weiweia oraz wideo, na którym w oddali na morskim horyzoncie majaczy niewyraźnie ponton. Ściany wytapetowane selfie artysty i śmierdzący gumą ponton unoszący się nad cytatami ze światowej literatury mogą wywołać podziw, ale także wielkie zdziwienie. Przesada, konsternacja, chwila zażenowania – artysta i aktywista, sam doświadczony przez życie jako uchodźca, dociera na greckie wyspy i co? Robi sobie selfie: z uciekającymi przed wojną dorosłymi, zabiedzony dziećmi, uśmiechniętymi wolontariuszami. Czy tak wypada?

Przepełnione pontony, zwłoki dziecka wyrzucone na brzeg, dramatyczne warunki w obozach, brutalnie traktujące uchodźców służby bezpieczeństwa. Te obrazy obiegały świat, wywołując wiele emocji, ale chyba za szybko się do nich przyzwyczailiśmy. Już nie działają na nas równie mocno jak za pierwszym razem, zdążyły się już nam nawet opatrzyć. Wywołują szok i współczucie, ale od wybuchu tzw. kryzysu uchodźczego przepłynęły ich przez światowe media miliony terabajtów.

Oglądając pokaz Ai Weiweia przypomniałem sobie pracę Glimpse, najnowszy film Artura Żmijewskiego prezentowany na documenta w Atenach. W dwudziestominutowym filmie zrealizowanym w Calais, Berlinie i Paryżu, Żmijewski nie próbuje być dobrym Europejczykiem i pomóc zmuszonym do tułaczki uchodźcom. Wręcz przeciwnie: jest bezlitosny, poniża kamerowane postaci, traktuje ludzi jak przedmioty: ukazuje sposób w jaki europejskie społeczeństwa traktują przybywających z Południa. Żmijewski dokonuje inspekcji namiotów, analizuje ciała czarnoskórych mężczyzn wcielając się w rolę kolonialnego antropologa. Ai Weiwei kładzie się w pozycji chłopca wyrzuconego na brzeg, który utonął w drodze do Europy i robi sobie zdjęcia w obozie dla uchodźców. Jeden oburza nas, rodzi sprzeciw – tak nie wolno, kto dał mu do tego prawo? Drugi, wykonujący setki zdjęć swojej twarzy w tak ekstremalnej sytuacji, też wywołuje wątpliwości – selfie wydają się przecież niepoważne, infantylne i nie na miejscu w obliczu kryzysu humanitarnego i mającej z założenia skłonić kogoś do refleksji wystawy.

Czy brutalny, pozbawiony ludzkich odruchów Artur Żmijewski lub uśmiechający się na zdjęciach, infantylny Ai Weiwei są do siebie podobni? Obaj łamiąc schematy, w jaki mówi się o uchodźcach chcą uświadomić nam, że ten kryzys wcale się nie skończył, a jedynie na chwilę zniknął z pierwszych stron portali informacyjnych. Jednak podczas gdy Żmijewski sieje ferment i każe nam skonfrontować się z własną pozycją, Ai Weiwei zdaje się podchodzić do problemu zupełnie bezrefleksyjnie.

Zastanawiając się nad spektakularnym dziełem chińskiego artysty w praskiej galerii, można mnożyć argumenty przeciwko tego typu realizacjom: wysokie koszty, nakręcanie kultu jednostki i gwiazdorskiego systemu sztuki czy oddanie palmy pierwszeństwa spektaklowi, a nie refleksji. W tym przypadku pojawia się jeszcze jeden argument, który zbić chyba najtrudniej: ten dotyczący wpływu pracy na środowisko naturalne, ujawniający hipokryzję artysty.

Sama tylko kolosalna ilość czarnego materiału, którą zużyto na projekt przeraża i każde spojrzeć na niego krytycznie. Przecież globalne migracje, chociaż na pierwszy rzut oka spowodowane jedynie polityką, walką o władzę i konfliktami zbrojnymi, mają także drugie dno – zmiany klimatyczne. Wystarczy przypomnieć, że długotrwała susza, trwająca w Syrii w latach 2006-2010, przyczyniła się do wielkiej migracji mieszkańców wsi do syryjskich miast i do rewolucji 2011 roku. Dziś z całą świadomością można powiedzieć, że globalne ocieplenie to jeden z czynników, które doprowadziły do wybuchu konfliktu w Syrii, a w rezultacie – wielkiego kryzysu humanitarnego. Na całym świecie w ciągu ostatnich sześciu lat około 140 milionów ludzi zostało zmuszonych do opuszczenia swojego miejsca zamieszkania ze względu na katastrofy wynikające ze zmian klimatycznych. W przyszłości liczby te będą jeszcze większe – według ONZ do 2050 roku jedna na trzydzieści osób może być zmuszona do migracji.

Setki życiorysów, które przewinęły się przez selfie Ai Weiweia stają się jego monumentalną pracą, a setki żyć straconych gdzieś tam przez chciwość, bezradność i ignorancję – tematem kolejnych wystaw.

Sam nie wiem, jak środowisko artystyczne mogłoby temu problemowi zaradzić i trudno mi powiedzieć, co artysta pokroju Ai Weiweia mógłby zrobić w tym kierunku, ale jedno jest pewne: w tym kontekście produkcja kolosalnego gumowego pontonu wydaje się wyjątkowo bezmyślnym pomysłem. Gigantyczny obiekt wskazywać ma na losy osób płynących do Europy, ale nie zdradza, skąd pochodzi cały materiał, z którego został wykonany. W jakich warunkach został wyprodukowany, jak przetransportowano go na miejsce wystawy i co się stanie się z nim po jej zakończeniu?

Kiedy czytamy cytaty wypisane na podłodze galerii, wystawa Ai Weiweia okazuje się jednak przede wszystkim opowieścią o tym, jak ludzka tragedia zamienia się w motyw w literaturze czy sztuce. Wszystkie te historie zawierają w sobie mnóstwo goryczy i smutku, ale zestawione razem stają się rodzajem katalogu bibliotecznego, zbioru aforyzmów: przecież ile takich książek przez lata napisano? Setki życiorysów, które przewinęły się przez selfie Ai Weiweia stają się jego monumentalną pracą, a setki żyć straconych gdzieś tam przez chciwość, bezradność i ignorancję – tematem kolejnych wystaw. W tym sensie wystawa bardziej niż o uchodźcach opowiada o mechanizmach, jakimi rządzi się kultura. Kiedy jednak dodamy to tego wspomniany wcześniej spot reklamowy, można odnieść wrażenie, że nikt nawet nie chce traktować problemu poważnie, a jedynie powielać jego reprezentacje.

Jednym z pytań nasuwających się podczas zwiedzania Galerii Narodowej jest także to, do kogo skierowana jest wystawa. Czy ma potencjał, by kogoś przekonać, chwycić za serce? Czy sława Ai Weiweia, monumentalizm jego prac i tona gumy mają taką moc? Jego praską wystawę traktować możemy także jako symptomatyczny przypadek wielkomiejskiego, liberalnego konformizmu z Europy Środkowej. „Liberalni, dobrze sytuowani Czesi przychylnie patrzą na Zachód i niechętnie w stronę Chin” – tłumaczy mi przy kawie znajoma. Dlatego właśnie chiński dysydent, a jednocześnie gwiazdor światowej sztuki to idealny sposób na przyciągnięcie ich do galerii. Wystawa Ai Weiweia odpowiada więc na potrzeby, spełnia oczekiwania zadowolonej z siebie publiczności, aspirującej do miana członków wspólnoty europejskiej. Law of the Journey nie zadaje pytań, nie podważa naszej pozycji, ani nie próbuje też sięgać do genezy problemu. Zamiast wskazywać na to, co konkretne społeczności mogłyby zrobić bądź co zrobiły w tej sytuacji źle, wystawa sprowadza problem do spraw uniwersalnych i odwiecznych pytań o kondycję człowieka-tułacza.

Wystawa Ai Weiweia w Národní galerie może rodzić wiele kłopotliwych pytań, ale to o bezpośrednią odpowiedzialność Europejczyków za sytuację na świecie w bardziej satysfakcjonujący sposób zadają inne odbywające się w Pradze wystawy. Artysta Oto Hudec w działającej w przestrzeni publicznej galerii Artwall zrealizował projekt Prague the Day After Bombing. Na wystawę składają się obrazy znanych praskich wież, punktów orientacyjnych i atrakcji turystycznych, które w ujęciu Hudeca są jednak w ruinie, zniszczone przez działania wojenne. Artysta naświetla w ten sposób przemilczany problem niekontrolowanego i rosnącego z roku na rok eksportu czeskiej broni i amunicji w obszary objęte działaniami wojennymi. Jak informuje Amnesty International, w 2015 roku Czechy wysłały broń do 34 krajów, w których łamane są prawa człowieka, równocześnie nie kontrolując do czyich rąk później ona trafia.

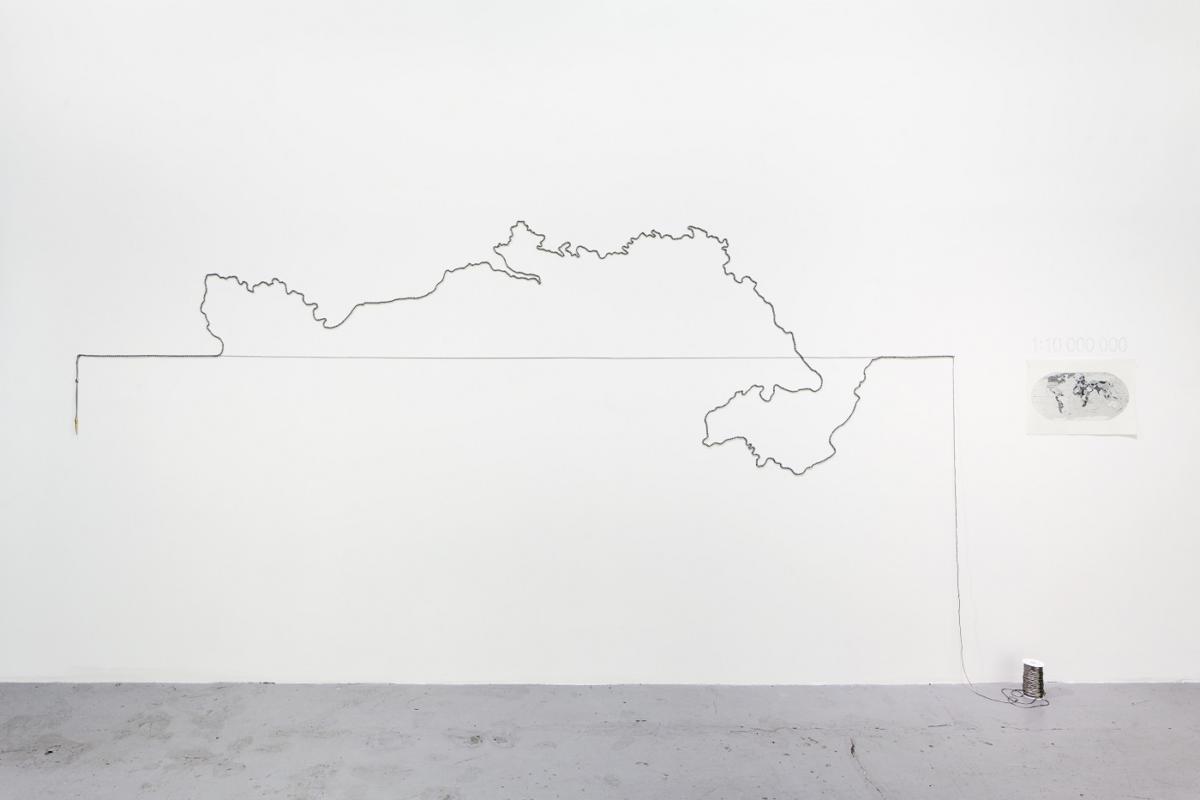

Kwestie odpowiedzialności, solidarności i stosunku Europejczyków do obcych, porusza wystawa Universal Hospitality 2 odbywająca się w MeetFactory i Futurze. Tu tematem staje się nie podróż, ale my – Polacy, Czesi, Węgrzy, to jak i dlaczego reagujemy na perspektywę spotkania z obcym. Oglądamy więc projekty odnoszące się do teraźniejszej sytuacji: znajdziemy tu prace Mariny Naprushkiny, która stworzyła serie poradników dla imigrantów, zawierające wskazówki prawne, jak radzić sobie przed urzędami w różnych państwach. Jest tu także film grupy Rafani analizujący działanie mediów, czy mapa autorstwa duetu Anca Benera i Arnold Estefan, na której najważniejszą i jedyną granicą jest ta dzieląca świat na globalną północ i południe. Inne prace opowiadają o genezie problemów, z jakimi zmagają się europejskie społeczeństwa: w swoim świetnym projekcie-muzeum Szabolcs KissPál zarysowuje powstanie nowej, populistycznej mitologii, jaką w swojej retoryce posługują się węgierscy nacjonaliści.

Wystawę przygotowało międzynarodowe grono kuratorów: Edit András, Birgit Lurz, Ilona Németh i Wolfgang Schlag. Aby być obcym w dzisiejszej Europie, nie trzeba być wcale uchodźcą pochodzącym z Syrii czy Afganistanu. Może przekonać się o tym pracująca nad ekspozycją historyczka sztuki i kuratorka Edit András, wykładająca na co dzień w Central European University w Budapeszcie. Na skutek nacjonalistycznej i antysemickiej nagonki rządu Victora Orbána na założony przez George’a Sorosa uniwersytet, uczelnia może być niedługo zmuszona opuścić Węgry i szukać miejsca dla siebie w innym kraju. Chociaż serdeczne zaproszenie do przeniesienia placówki do swojego miasta złożyli uniwersytetowi już między innymi włodarze Pragi i Wiednia, sytuacja przypomina o tym, jak kruche bywają podziały na „obcych” i „naszych”.

Ai Weiwei, Law of the Journey

Národní galerie v Praze – Veletržní palác

Kurator: Jiří Fajt we współpracy z Adamem Budakem

Otto Hudec, Prague the Day After Bombing

Artwall Gallery

Kuratorki: Zuzana Štefkova, Lenka Kukurová

Universal Hospitality 2

MeetFactory, Kostka Gallery, Futura

Kuratorzy: Edit András, Birgit Lurz, Ilona Németh, Wolfgang Schlag

[1] politicalcritique.org/cee/czech-republic/2016/when-xenophobes-have-a-holiday/

[2] http://politicalcritique.org/events/2016/statement-of-the-klinika-collective/

ENG

In the latest video promoting the National Gallery of Prague there is a slow-motion shot of the feet of visitors admiring the exhibition. The footwear indicates who they are: we see military boots, yellow sneakers, children’s shoes. In a flash of awe the characters drop their attributes: a nun drops her rosary, a child its teddy bear, a soldier his mess tin, and a teenage girl: her set of earphones. The story, however, does not end here. Among the visitors there is also a barefoot refugee who we get to see as he drops a still wet lifejacket. Meanwhile, a male voice-over introduces exhibitions of great artists: Gerhard Richter, Magdalena Jetlova, and Ai Weiwei.

In Prague, just as in the entire Czech Republic, refugee presence is virtually nonexistent. According to the EU agreements, the country should accept 1600 people. It accepted 12. In February last year, several thousand demonstrators in Prague opposed opening state borders and the „islamisation of Europe”[1]. A few hours after the rally, a number of masked men attacked the autonomic centre for culture called „Klinika”, engaged in providing help to refugees[2]. Still, even though refugees are rarely seen on Czech streets, they are strongly represented in Czech art: apart from the Národní Galerie they appear in the engagé Universal Hospitality 2 at MeetFactory, focused on a critical reflection on Central Europe’s hospitality, or rather lack of it.

The National Gallery is proudly inviting the audience to visit both Czech Republic’s and Middle-Eastern Europe’s first display of the Chinese artist’s oeuvre.

Národní Galerie has survived a tough period under the management of Milan Knížák, a Fluxus-connected artist, who ran the institution for over a decade (1999-2011) and treated it as his own property. The latter led to a situation where for a long time the gallery was no point of reference for the Czech artistic community when it came to discussing contemporary art. As of 2014, Jiří Fajt has been holding the reins, and although the progress is clearly visible (the gallery has become friendlier, enhanced its international presence and made efforts to attract new audiences), the artistic circles are still hardly enthusiastic about the institution’s current programme, focused of blockbusters and heavyweight names. It is enough to take a look at the gallery’s latest offering: several of its branches are now simultaneously housing exhibitions of top-drawer artists from the Czech Republic, Germany and China. The last of the three is the one which so far has provoked most polarised reactions and resulted in criticisms of both itself and Jiří Fajt’s policies in general: star names, expensive tickets and not much else (except, maybe, for the museum’s café).

The Law of the Journey exhibition of Ai Weiwei’s work is presented in the monumental interiors of the Veletržni Palace. The National Gallery is proudly inviting the audience to visit both Czech Republic’s and Middle-Eastern Europe’s first display of the Chinese artist’s oeuvre. In several rooms the artist’s realisations from the last decade have been laid-out. They all deal with terrifying politics and human suffering. All are meant to reflect how deeply Ai Weiwei cares about the world’s most acute problems.

The walls wallpapered with the artist’s selfies and a large stinking rubber dinghy dangling over quotes from international literature may produce awe, but also great surprise.

Just below the ceiling of the museum’s hall hangs a giant serpent made from school bags: each one represents one of the pupils who died in the earthquake that struck the Chinese province of Sichuan back in 2008. The walls of the hallway leading to the main room are covered in horizontal black and white representations of scenes from a refugee’s life: fleeing, wandering, nomadic life in tents set against a backdrop of barb-wires. The most important item here, however, is a gigantic rubber dinghy hanging over the floor. It is huge, dark, full of cramped anonymous individuals. It overwhelms us the moment we enter that large room. Beneath it, on the floor, we find written quotes relating both to he current situation in Syria (Samar Yazbek), and to issues such as the human condition and human rights (Václav Havel).

The very situation of the gallery is also of significance when it comes to the topics of the exhibition: wandering and displacement. Between 1939 and 1941 this modernist palace acted as a transfer hub for the Czech Jews sent from here to, among other places, the Lodz ghetto. The memory of those events brings about the genesis of today’s phobias of Central European societies, so hostile towards refugees. Brutal as it may sound, modern day societies of the Czech Republic, Poland or Hungary are this homogenous basically because of the acts of extermination during WWII and the migrations to Israel that followed.

On the lateral walls of the monumental room we can see a photographic record of Ai Waiwei’s travel and a video showing a maritime horizon with a blurry dinghy showing far in the distance. The walls wallpapered with the artist’s selfies and a large stinking rubber dinghy dangling over quotes from international literature may produce awe, but also great surprise. Exaggeration, consternation, a whiff of embarrassment: an artist and an activist, with own experience as a refugee, reaches the Greek islands, and does what? Starts taking selfies with adults fleeing from warzones, gaunt children and smiling volunteers. Isn’t this something of bad taste?

Overcrowded rubber boats, a child’s dead body washed out on the shore, truly dramatic conditions in the camps, and the guards’ brutality: the images of all that spread around the globe causing much stir, but we seem to have gotten used to them rather too quickly. We are no longer moved by them as much as we were the first time. Actually, they’ve lost most of their „appeal”. They do produce shock and sympathy, but since the beginning of the so-called refugee crisis the media have shown us terabytes of them. While looking at the Ai Weiwei exhibition I remembered Glimpse, Artur Żmijewski’s latest film presented at the documenta in Athens. In this 20-minute video, shot in Calais, Berlin and Paris, Żmijewski does not attempt to be a good European trying to aid refugees who were forced to wander. On the contrary: he is genuinely ruthless. He humiliates the characters he films and treats people like objects, thus showing how European societies approach newcomers from the south. Żmijewski performs an inspection of refugees’ tents and plays a role of colonial anthropologist by examining the bodies of black men. Ai Weiwei lies on the shore imitating the dead boy who drowned on the way to Europe; he then takes pictures and selfies inside a refugee camp. The first artist causes our indignation and dissent: „One should not do such things! Who gave him the right to act this way?”, we think. The other, by taking hundreds of pictures of his own face in such extreme circumstances, also leaves us perplexed: his selfies just seem so immature, infantile and out of place, both in light of the humanitarian crisis and as part of an exhibition which is basically supposed to make people reflect on things.

Are the brutal and unscrupulous Artur Żmijewski and the infantile Ai Weiwei smiling in the pictures alike? Both of them, neglecting the usual templates we apply to talk about refugees, try to make us see that the crisis if far from over. It just disappeared from the front pages for a while. Still, while Żmijewski causes unrest and forces us to confront our outlooks, Ai Weiwei seems to act in a way devoid of reflection.

When reflecting on the Chinese artist’s spectacular display in the Prague gallery, one will easily find numerous arguments against such realisations: high cost, encouragement of personality cult and a celebrity-focused artistic reality, or giving way to spectacle at the expense of reflection. In this particular case, there is one more argument, probably the hardest one to defeat. It is about the artist’s work impact on the environment, which denounces his hypocrisy.

The sheer volume of the black material used in the project is mind-bogglingly worrying and deserves our disapproval. After all, even though it may appear that global migrations are solely caused by politics, armed conflicts and struggle for power, there is a second aspect here which is climate change. It is worth remembering that the prolonged draught that lasted in Syria between 2006 and 2010 caused massive migration of rural people to cities, which in turn led to the revolution of 2011. Today, we can be adamant that global warming was one of the factors which sparked off the conflict in Syria and, in consequence, led to a major humanitarian crisis. Globally, over the last six years one hundred and forty million people have been forced to leave their homes due to calamities resulting from climate change. In the future, this figure is bound to grow. According to the UN, by 2050 one in thirty people can be forced to migrate.

Hundreds of biographies weaved into Ai Weiwei’s selfies add up to become his monumental work, hundreds of lives lost due to greed, helplessness or ignorance become topics of more and more exhibitions.

Personally, I neither know how the artistic circles could help solve this problem, nor how artists like Ai Weiwei could contribute. But one thing I do know for certain: considering the context described above it seems completely careless to come up with a giant rubber dinghy. That gargantuan object was meant to reveal the fate of people struggling to reach Europe, but it does not reveal the source of all the material that went into its construction. Neither do we know where and by whom it was made, how it got transported to the gallery, or what will become of it once the exhibition is over.

When we focus on the quotes on the gallery floor, however, Ai Weiwei’s exhibition turns out to be first of all a tale of how human tragedy becomes a motif for literature and art. All the stories here are full of bitterness and anguish, but juxtaposed all together they become a library index of sort, a collection of aphorisms. I mean: how many books of this kind have been written over the years? Hundreds of biographies weaved into Ai Weiwei’s selfies add up to become his monumental work, hundreds of lives lost due to greed, helplessness or ignorance become topics of more and more exhibitions. In this respect, the exhibition is not so much about refugees as it is about the mechanisms ruling culture. Once, however, we add to that the aforementioned promotional video, we can be left with the impression that no one here is even willing to approach the problem seriously: they are just interested in multiplying its representations.

One of the questions we’re likely to ask ourselves while visiting the Prague National Gallery is who this exhibition is aimed at. Does it have the potential to genuinely touch someone’s heart? To convince somebody? Are Ai Weiwei’s fame, the monumentality of his works, and a tonne of rubber powerful enough to do it? We can perceive his exhibition in Prague also as a very telling example of liberal urban conformism of Central Europe. „Liberal, well-off Czechs look favourably at the West and frown on China”, a friend explains to me over coffee. That is the reason why a Chinese dissident who at the same time is an international artistic celebrity is a perfect brand to attract that kind of audience. Ai Weiwei’s exhibition suits the needs and satisfies the requirements of smug visitors aspiring to being part of the European community. Law of the Journey neither asks questions, nor challenges our position. It does not aim to get to the origin of the problem. Instead of pointing out which specific communities could do what, or what kind of errors they committed, the exhibition narrows the problem down to universal issues and age-old questions about the condition of a wandering man.

Ai Weiwei’s exhibition in Narodní Galerie can bring about numerous uncomfortable questions. However, the one about Europe’s direct responsibility for the global situation is asked in a more satisfying way by other exhibitions currently displayed in Prague. The artist Oto Hudec completed, in a gallery located in a public space and called Artwall, a project titled Prague Day After Bombing. The exhibition comprises paintings of the city’s famous towers, landmarks and tourist attractions. Those, however, in Hudec’s version are in rubble, destroyed by military actions. This way the artist highlights the passed-over problem of annually growing, uncontrolled exports of Czech weapons and ammo to warzones in different parts of the world. Amnesty International revealed that in 2015 alone the Czech Republic sent weapons to 34 countries in which human rights are violated, without any scrutiny regarding the end user.

The issues of responsibility, solidarity and Europeans’ attitude towards strangers are dealt with by Universal Hospitality 2, an exhibition held at MeetFactory and the Futura. Here, the main subject is not wandering, but us, meaning Poles, Czechs, Hungarians, and how and why we react to the prospect of meeting a stranger. We are therefore shown projects referring to the current situation. There are works by Marina Naprushkina who created a series of guides for immigrants containing legal advice and tips on how to deal with state offices in different countries. There are also a video by the Rafani group analysing media activity, and a map by the Anca Benera and Arnold Estefan duo where the only border dividing our world is the one between the global North and South. Other works here focus on the origins of problems now faced by European societies: in his fantastic museum-like project Szabolcs KissPál drafts the birth of a new populist mythology applied within the Hungarian nationalists’ rhetoric.

The exhibition was prepared by an international team of curators: Edit András, Birgit Lurz, Ilona Németh, and Wolfgang Schlag. In order to be perceived as an alien in today’s Europe one does not at all need to be a refugee from Syria or Afghanistan: a fact directly experienced by Edit András, art historian and curator, who worked on the exhibition. On a daily basis she is a lecturer at the Central European University in Budapest. Now, due to a nationalist and anti-Semitic witch-hunt inspired by Victor Orban’s government George Soros’ university may be forced to abandon Hungary and search for a place in another country. Even though the school has already received cordial invitations from the authorities of Prague and Vienna, the whole situation reminds us of just how fragile the division between „aliens” and „locals” sometimes is.

Ai Weiwei, Law of the Journey

Národní galerie v Praze – Veletržní palác

Curator: Jiří Fajt in collaboration with Adam Budak

Otto Hudec, Prague Day After the Bombing

Artwall Gallery

Curators: Zuzana Štefkova, Lenka Kukurová

Universal Hospitality 2

MeetFactory, Kostka Gallery, Futura

Curators: Edit András, Birgit Lurz, Ilona Németh, Wolfgang Schlag

[1] politicalcritique.org/cee/czech-republic/2016/when-xenophobes-have-a-holiday

[2] http://politicalcritique.org/events/2016/statement-of-the-klinika-collective

This article was produced under East Art Mags, a residency program for critics from Central and Eastern Europe. Jakub Gawkowski’s residency in Prague was made possible thanks to the generous support of AFCN and the Polish Institute in Bucharest.

This article was produced under East Art Mags, a residency program for critics from Central and Eastern Europe. Jakub Gawkowski’s residency in Prague was made possible thanks to the generous support of AFCN and the Polish Institute in Bucharest.

Jakub Gawkowski — jest kuratorem i historykiem sztuki, pracuje w dziale sztuki nowoczesnej Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi. Absolwent Uniwersytetu Środkowoeuropejskiego w Budapeszcie. Kurator i współkurator wystaw m.in.: Erna Rosenstein, Aubrey Williams. Ziemia otworzy usta (Muzeum Sztuki, 2022), Atlas Nowoczesności. Ćwiczenia (jako część zespołu kuratorskiego, Muzeum Sztuki, 2021), Ziemia znów jest płaska (Muzeum Sztuki, 2021), Agnieszka Kurant. Erroryzm(Muzeum Sztuki, 2021), Die Sonne nie Świeci tak jak słońce (Trafostacja Sztuki, 2020), Diana Lelonek. Buona Fortuna (Fondazione Pastificio Cerere, 2020), Najpiękniejsza Katastrofa (CSW Kronika, 2018). Stypendysta European Holocaust Research Infrastructure oraz programu DAAD theMuseumsLab 2022.

Więcej