Strach pożera duszę. Fragmentaryczny raport o sytuacji w węgierskiej kulturze / Fear Eats the Soul: A Partial Report on Hungarian Contemporary Culture

For English version scroll down

PL

Mijają dwa lata, odkąd cieszący się międzynarodowym uznaniem reżyser teatralny i aktywista Árpád Schilling stwierdził gorzko w jednym z wywiadów: „Konsensus, który do pewnego stopnia spajał społeczeństwo węgierskie z jego elitami politycznymi, dobiegł końca. Nastąpił rozpad”[1].

Wypowiedź ta padła tuż po premierze spektaklu Loser, w którym dyrektor-założyciel teatru Krétakör trafił w wiele społecznie czułych punktów, obsadzając się w roli rozgniewanego, radykalizującego się intelektualisty, który wdaje się w niemożliwy do zażegnania konflikt, jakim jest próba pogodzenia bezkompromisowego zaangażowania politycznego z zachowaniem autonomii wypowiedzi artystycznej. Diagnoza Schillinga oparta jest na jego przeszło dwudziestoletnich doświadczeniach w pracy z zaangażowanym krytycznie teatrem, pracą na rzecz budowania społeczności, a także na publicznym odnoszeniu się do odchyleń w dziedzinach kultury i polityki, którym to zawdzięcza Krétakör otrzymanie w 2016 roku prestiżowej Nagrody im. Księżniczki Margriet[2]. Decyzja Krétaköra z 2008 roku, aby zaprzestać tworzenia „tradycyjnych” przedstawień, wskazuje na zmianę perspektywy i poglądu w kwestii tego, jak uprawiać sztukę, aby prowadziła ona do zmiany – z jednej strony przez obalenie czwartej ściany, z drugiej – przez łączenie teatru i metod dydaktyki dramatycznej przy jednoczesnym tworzeniu krytycznej publiczności[3]. Dylematy ukazane w spektaklu Loser dotyczą wielu ludzi ze świata kultury i spoza niego – zwłaszcza tych, którzy dyscypliny artystyczne postrzegają jako złożone, kulturalne, edukacyjne i zaangażowane społeczno-politycznie medium funkcjonujące w ramach coraz to mniej demokratycznej działalności państwa. W kwietniu tego roku Schilling opublikował ostry wideomanifest – ubrany w bokserki, odnosi się w nim bezpośrednio do rządowego kwestionariusza konsultacyjnego „Powstrzymajmy Brukselę!”, będącego kolejnym już manipulatorskim ruchem władz mającym za zadanie usprawiedliwianie jej działań[4]. Narastający gniew, któremu artysta dawał wyraz w ostatnich wywiadach, przełożył się na wezwanie do nieposłuszeństwa obywatelskiego, nieakceptowania dalszych wymówek i zarzucenia bierności w zakresie walki z rządem.

Árpád Schilling, spektakl Loser, Trafó Galéria, Budapeszt, 2014, fot. Sándor Fegyverneky,

dzięki uprzejmości

teatru Krétakör

Nadane przez władzę uprawnienia i koncesje uczyniły z HAA niemal kolejne ministerstwo, które szybko stało się wyłączną instancją decydującą o podziale obowiązków i sposobie administrowania w dziedzinie węgierskiej kultury i sztuki.

Choć istnieją złożone powody historyczne poprzedzające dzisiejszy kryzys, to większość najbardziej palących kwestii w sektorze kultury stanowi bezpośrednią konsekwencję dogłębnie zepsutej i destruktywnej polityki obecnego reżimu oraz prowadzonych przez niego kampanii ideologicznych[5]. Po przejęciu państwa przez Fidesz pozytywne zmiany i przekształcenia w sektorze kultury współczesnej szybko zaczęto demontować, a do głosu doszli antyintelektualni krytykanci stawiający sobie za cel dyskredytowanie niewygodnych wypowiedzi krytycznych i narracji medialnych[6]. Już w latach 2011–2012 nie tylko pogorszyła się sytuacja ekonomiczna większości instytucji i niezależnych organizacji finansowanych przez państwo bądź miasta, ale doszło również – wraz z wprowadzeniem nowej konstytucji – do nadania ultrakonserwatywnej Węgierskiej Akademii Sztuki (HAA)[7] statusu organizacji pożytku publicznego. Przełożyło się to na dosłowne nafaszerowanie tego podmiotu państwowymi pieniędzmi (obok zresztą bliskich władzy organizacji obywatelskich, mediów i lojalnych dyletantów) i przekazanie mu, między innymi, tak ważnych miejsc jak, Pałac Sztuki (Műcsarnok) w Budapeszcie. Nadane przez władzę uprawnienia i koncesje uczyniły z HAA niemal kolejne ministerstwo, które szybko stało się wyłączną instancją decydującą o podziale obowiązków i sposobie administrowania w dziedzinie węgierskiej kultury i sztuki, w tym w obrębie literatury, muzyki, sztuk pięknych, sztuki stosowanej, wzornictwa, architektury i tak dalej, a także w zakresie teorii, edukacji kulturalnej oraz lokalnego i międzynarodowego wystawiennictwa i reprezentacji artystów. W kwestiach publicznych przestała obowiązywać zasada równego traktowania. Nominacje dyrektorskie oparte są w większości na sympatiach politycznych i nepotyzmie, do czego dochodzi w sferach partii rządzącej. Zmian na stanowiskach w kulturze dokonuje się niemal bez zwracania uwagi na kryteria zawodowe i wizję. Służące szerszej polityce centralizacji i kontroli przez ministerialne departamenty liczne decyzje władz o restrukturyzacjach w muzealnictwie, archiwach krajowych czy dziedzinach dziedzictwa narodowego i sektora akademickiego odbywają się z rażącym pominięciem jakiejkolwiek debaty merytorycznej i przy braku zrozumienia wymogów praktycznych.

W 2017 polityczny i społeczny kryzys pogłębił się: nasiliła się retoryka antyimigrancka i antyunijna wspierana kampaniami medialnymi i billboardami, doszło do kolejnych naruszeń praw mniejszości, cięć w zapomogach społecznych, regresu w edukacji i opiece zdrowotnej oraz do wszczęcia przez władze szeroko zakrojonej wojny z finansowanymi przez podmioty międzynarodowe instytucjami i organizacjami pozarządowymi. Te ostatnie wprost nazwano zagrożeniem dla kraju, co najwyraźniejszy oddźwięk znalazło w niedawnej, powszechnie krytykowanej ustawie o organizacjach pozarządowych[8] (w której pobrzmiewają echa wprowadzonej w Rosji w roku 2012 ustawy „antyagenturalnej”) oraz tak zwanego Lex CEU – wymierzoną nie tylko w międzynarodową prywatną uczelnię (założoną w 1991 roku, a w 1993 roku przeniesioną do Budapesztu), ale i w amerykańsko-węgierskiego miliardera George’a Sorosa, którego Fundacje Społeczeństwa Otwartego wspierają liczne projekty i organizacje pozarządowe[9]. Po zapiekłej rozprawie z mediami na celowniku znalazły się także niewielkie ośrodki alternatywne, takie jak rozkwitające lewicowe centrum aktywistyczno-społeczne Aurora goszczące osiem organizacji pozarządowych skoncentrowanych na działalności na rzecz grup marginalizowanych i stygmatyzowanych, ale prowadzących także programy kulturalne obejmujące odczyty i dyskusje. Wobec działań systemu cechującego się zinstytucjonalizowaną korupcją, szerzeniem społecznych nierówności i zastraszaniem pracowników sektora publicznego – a wszystko to oparte na niegasnącym cynizmie i nieustannym szerzeniu nienawiści – satyryczne kampanie plakatowe Magyar Kétfarkú Kutya Párt (MKKP), czyli Partii Psa o Dwóch Ogonach, oddolnej grupy aktywistów wykorzystującej absurdalny humor jako oręż polityczny, czy pojawienie się nowych ruchów politycznych, takich jak Momentum[10] i Common Country, formacji założonej przez blogera i byłego dyrektora wykonawczego Krétaköra, Mártona Gulyása[11], sygnalizują palącą potrzebę zaprowadzenia zmiany zmierzającej ku odmiennej, odpowiedzialnej postawie i retoryce w dziedzinach kultury i działalności politycznej.

Wiele osób związanych zawodowo z kulturą mierzy się z trudnymi wyborami, usiłując zachować resztki niezależności zawodowej i podtrzymać regionalną i międzynarodową świadomą współpracę na polu sztuki współczesnej, kultury czy muzealnictwa[12]. Odrzucenie dobrej praktyki zarządzania, a raczej – należałoby powiedzieć – całkowity rozwód z działaniem demokratycznym, pogłębiło tylko erozję publicznego systemu, w którego gestii pozostają instytucje kultury i muzealnictwo. Do końca roku 2016 pięć finansowanych przez państwo instytucji zajmujących się ochroną dziedzictwa, muzealnictwem i edukacją kulturalną zostało zamkniętych w celu „reorganizacji”. Było pośród nich Magyar Nemzeti Digitális Archívum [MaNDA; Węgierskie Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe][13]. Niektóre instytucje już zostały zreorganizowane zgodnie z myślą reżimu. Systematyczne, zideologizowane przejmowanie i zdalna kontrola nad instytucjami, brak autonomii strukturalnej i programowej oraz sfeudalizowany system, w którym dziedzictwo kulturowe postrzega się wyłącznie w relacji do tożsamości narodowej, wieńczy jak wisienka na torcie arogancki antyprofesjonalizm, a wszystko przynosi kolejne szkody w zakresie zmian instytucjonalnych[14]. Podczas gdy liczne budapeszteńskie muzea walczą o zaspokojenie swoich elementarnych potrzeb, a sytuacja poza stolicą jest jeszcze bardziej dramatyczna, otwiera się wiele trwałych i tymczasowych przestrzeni reprezentacyjnych, które goszczą projekty historyczne i kulturalne zarządzane przez biznesowe grupy inwestycyjne, serwowane odbiorcom przez wybranych nadwornych kuratorów i doradców[15]. System skoncentrowanych wokół rocznic grantów to kolejne szkodliwe rozwiązanie, które uderza w dalekowzroczne, profesjonalne planowanie i zwiększa zależność instytucji od programów motywowanych politycznie, angażując je w manipulatorskie niejednokrotnie narracje rządowe.

Powołane w 2015 roku OFF-Biennale Budapest także zadeklarowało, że nie będzie korzystać ze wsparcia państwa i oferowanych przez nie przestrzeni.

W niedawno opublikowanej na łamach miesięcznika artystycznego „Műértő” profesjonalnej analizie historyczka sztuki i krytyczka Edit András wskazywała na taktykę odrębnego traktowania różnych gałęzi kultury za sprawą działań transformacyjnych tak, aby instytucje kultury i sztuki odczuwały ciężar wyłącznie w obrębie swojego sektora[16]. Kurator i kierownik Fiatal Képzőművészek Stúdiója Egyesület [FKSE; Studio Stowarzyszenia Młodych Artystów] Eszter Kozma podkreśla, że „restrukturyzacja” systemu instytucjonalnego przekłada się nie tylko na kryzysy egzystencjalne i zawodowe, ale i na szereg (dodałabym – pogłębiających się i sprzyjających podziałom) dylematów moralnych. Jednym spośród nich jest pytanie, czy wikłać się w stronniczy systemem grantów i uczestniczyć w skorumpowanej dystrybucji środków. FKSE opublikowało pod koniec 2012 roku manifest, w którym ogłasza wycofanie się z rady kuratoryjnej Węgierskiego Narodowego Funduszu Kultury oraz wstrzymanie składania jakichkolwiek wniosków z uwagi na naganne działania tej instytucji. Wobec kluczowej roli scentralizowanego finansowania państwowego na scenie artystycznej i braku wielokanałowej strategii słaby lokalny rynek sztuki i wątłe międzynarodowe sieci zmuszone są do zarzucania swoich praktyk bądź – jak w przypadku licznych inicjatyw artystycznych i kuratorskich – mierzą się z koniecznością ponoszenia ogromnych nakładów w postaci pracy pro bono i stosowania samowyzysku. Powołane w 2015 roku OFF-Biennale Budapest także zadeklarowało, że nie będzie korzystać ze wsparcia państwa i oferowanych przez nie przestrzeni.[17] Jednakże stawką i kwestią zyskującą tu kluczowe znaczenie – nie tylko dla OFF-Biennale, ale dla wszystkich podtrzymujących praktykę krytyczną w ramach systemu instytucjonalnego – jest to, jak przywrócić „odbiorców” publicznej infrastruktury instytucjonalnej, odzyskać środki, gwarantowaną przez państwo autonomię i demokratyczną metodę działania na dłuższą metę. Wielu, zarówno spośród uznanych artystów starszych pokoleń, jak i wschodzących artystów i kuratorów, którzy dopiero niedawno ukończyli akademie, ma poczucie funkcjonowania w próżni. Skrajne zróżnicowanie środowiska twórczego doprowadza do tego, że są oni często zależni od grona prywatnych mecenasów, kolekcjonerów i właścicieli galerii, pośród których część jest wprost związana z władzą, a powiązania z interesami państwa innych są nieco mniej przejrzyste.

Podczas gdy kluczowe swego czasu instytucje, jak Pałac Sztuki w Budapeszcie, zostały w mniejszym bądź większym stopniu wymazane z krytyczno-artystycznej mapy Węgier, Ludwig Múzeum – Muzeum Sztuki Współczesnej – choć już bez wcześniejszego dyktatorskiego, konsekwentnego i strategicznego programowania i zaangażowania w badania – prezentuje nieco przypadkiem projekty dobrej jakości, jak choćby ruchome Dzikie pola. Historia awangardowego Wrocławia, niedawna retrospektywa połowy kariery malarza Attili Szűcsa zatytułowana Specters and Experiements czy ekspozycja poświęcona neoawangardowej działalności Pracowni Pécs.

W gronie osób, które prędzej czy później opuściły Ludwig Múzeum po kontrowersyjnej wymianie dyrektorów w 2013 roku, są Emese Kürti i Róna Kopecky, które kontynuowały następnie swoją działalność i badania już tylko w celach zarobkowych. Kopecky została współdyrektorką artystyczną galerii acb, ale też współprowadziła przez cztery lata „Easttopics”, projekt online poświęcony promowaniu wschodnioeuropejskiej sztuki współczesnej. Znajdziemy tu także historyczkę sztuki i kuratorkę OFF-Biennale Katalin Székely, obecnie dyrektorkę kreatywną i programową Open Society Archives (OSA), a wcześniej redaktorkę publikacji Bookmarks – projekt ten wspierany był przez kolekcjonerów i czołowe galerie. Premiera przedsięwzięcia miała miejsce podczas kolońskich Targów Sztuki Nowoczesnej i Współczesnej w 2015 roku. Székely poddała analizie najistotniejsze pozycje węgierskiej neoawangardy i sztuki postkonceptualnej, od późnych lat 60. aż do dzień, z uwzględnieniem artystów, takich jak Dóra Maurer, Tamás Szentjóby, Little Warsaw czy Gyula Várnai, którego wystawę znajdziemy w Pawilonie Węgierskim na tegorocznym Biennale w Wenecji[18]. Swoista kontynuacja czy – jak kto woli – amerykańska premiera projektu, do którego zostali zaproszeni nieco inni artyści, odbyła się tego lata przez Elizabeth Dee Gallery w Nowym Jorku.

Wobec obserwowanego załamania instytucjonalno-zawodowego także istotna część badań nad kulturalno-artystycznym dziedzictwem okresu socjalizmu (reżimu Kádára) trafiła do sektora prywatnego, w tym – niedawno otwartego ResearchLab galerii acb, powstałego we wrześniu 2015 roku. Profil tego ośrodka, kierowanego przez historyczkę sztuki Emese Kürti, obejmuje między innymi przygotowanie publikacji międzynarodowych i prezentacji monograficznych poświęconych węgierskiej neoawangardzie i postawangardzie, z uwzględnieniem twórczości takich postaci jak poetka i performerka Katalin Ladik. Pojawiły się zaniepokojone głosy, że ekspozycje motywowane zarobkowo zestawione z dość skromnymi rozmiarami galerii mogą poskutkować zniknięciem części artystycznego dziedzictwa Węgier okresu zimnej wojny (a niedługo później – dorobku lat 90.). Wyrażano obawy, że nie wejdą one do kanonu z powodu braku trwałej, zinstytucjonalizowanej i złożonej ekspozycji, krytycznej prezentacji, a także badań społeczno-historycznych[19].

Wciąż jednak istnieje w systemie muzealniczym przestrzeń dla działalności krytycznej. Bezdyskusyjnie jedną z najważniejszych placówek jest w tym kontekście Kassák Múzeum – dyrektor, historyczka sztuki Edit Sasvári, tworzy od roku 2010 uznaną międzynarodowo placówkę z własnym zespołem. Opierając się na spuściźnie (zarówno literackiej, publicystycznej, jak i z zakresu sztuk wizualnych) modernistycznego malarza, pisarza, wydawcy i publicznego rozjemcy Lajosa Kassáka, udało się przekształcić martwą przestrzeń wystawienniczą w centrum spotkań młodych badaczy i historyków, których dorobek poddaje się tu krzyżowemu badaniu z punktu widzenia historii społecznej i politycznej. W 2012 roku zainicjowano długofalowy, oparty na badaniach projekt „Life Reform and Social Movements in Modernity”, aby „zapewnić przestrzeń dla prezentowania drażliwych społecznie kwestii i projektów artystycznych”. Muzeum prowadzi także zakrojone na wiele lat badania dotyczące sztuk wizualnych lat 60. i 70., proponując „nowe rozumienie skupione na kontekście regionalnym, mające zastąpić zarówno izolowany pogląd nacjonalistyczny, jak i dychotomię centrum–peryferie”. Etnografka i krytyczka Zsófia Frazon działa aktywnie na rzecz wzmocnienia dialogu międzykulturowego między odrębnymi dyscyplinami i jest mocno zaangażowana w projekt „Curatorial Dictionary” pod kierunkiem kuratorki Eszter Szakács z Tranzit.hu. Mimo nieustannych trudności Węgierski Uniwersytet Sztuk Pięknych (MKE) z powodzeniem uruchomił we wrześniu 2009 roku studia licencjackie z zakresu teorii sztuk pięknych, w roku 2010 powołał Wydział Teorii Sztuki, zaś obecnie przygotowuje się do wdrożenia programu magisterskiego w dziedzinie teorii sztuki współczesnej i studiów kuratorskich.

Istnieją także w obrębie sceny niezależnej od państwa formaty ułatwiające wymianę międzynarodową i promujące lokalne działania przez swoje sieci kontaktów – za przykład mogą posłużyć tutaj Tranzit.hu czy kuratorski duet Maja i Reuben Fowkesowie. Program kuratorskiego duetu, od roku 2013 działającego pod szyldem Translocal Institute, łączy dyskurs akademicki z kuratorskim przez kładzenie wyraźnego nacisku na zrównoważenie, ekologię i antropocen oraz angażowanie się w długofalowe studia wschodnioeuropejskiej sztuki neoawangardowej. Tranzit.hu, zmieniający właśnie siedzibę i ulegający pewnej transformacji, podejmuje całe mnóstwo działań, od cyklu bezpłatnych lekcji i prowadzenia bloga kulturalnego po projekty mocniej oparte na aktywizmie, jak choćby wyróżniona nagrodą Catalyst dla postępowych inicjatyw kulturalnych seria Action Day czy uruchomiony niedawno międzynarodowy internetowy magazyn artystyczno-kulturalny „Mezosfera”. Rzadko zdarza się, by w przestrzeni artystycznej utrzymywał się względny spokój pozwalający konsekwentnie budować program. Wyjątkiem jest tutaj galeria działająca w ramach finansowanego przez państwo i miasto Trafó – współtwórcy OFF-Biennale, gdzie kuratorzy Áron Fenyvesi i Borbála Szalai skupili się na różnorodnych przykładach sztuki konceptualnej, performatywnej i postabstrakcyjnej, tak miejscowej, jak i reprezentującej kraje Grupy Wyszehradzkiej.

Plac Wolności pozostał jedną z głównych scen toczącej się właśnie gry o pamięć polityczną oraz prowadzonej przez obecny rząd polityki „stanu amnezji” – to tu od kwietnia 2014 roku działa grupa The Living Memorial powstała w akcie protestu przeciw mocno krytykowanej instalacji rzeźbiarskiej stanowiącej pomnik ofiar niemieckiej okupacji.

Ostatnie lata pokazały też jednak boleśnie i wyraziście braki po dekadach, które nastały po zmianie reżimu w 1989 roku – to, jak niewiele miejsca pozostawiono, zarówno fizycznie, jak i intelektualnie na stawianie czoła kontrowersjom i złożonościom historii oraz intelektualno-politycznej spuściźnie ostatniego stulecia. Dość przyjrzeć się trwającemu sporowi prawnemu między Instytutem Historii Politycznej a państwem czy sporom toczonym w Węgierskiej Akademii Nauk w związku ze statusem i przyszłością Archiwum Györgya Lukácsa. Działania władz, stanowiące w większości pochodną wymogów administracyjnych, grożą długotrwałym wstrzymaniem dostępu do niego na użytek badawczy i możliwości korzystania z infrastruktury, ale także – nieprofesjonalnym obchodzeniem się z materiałami, izolowaniem ich lub ukrywaniem drażliwszych elementów dziedzictwa[20]. Niedawne usunięcie pomnika Lukácsa to kolejny z wielu rządowych kroków mających na celu przearanżowanie przestrzeni miejskiej zgodnie z własnym programem i polityką historyczną.

Plac Wolności pozostał jedną z najbardziej operowych scen toczącej się obecnie gry o pamięć polityczną oraz prowadzonej przez obecny rząd polityki „stanu amnezji”[21] – to tu od kwietnia 2014 roku działa grupa The Living Memorial powstała w akcie protestu przeciw mocno krytykowanej instalacji rzeźbiarskiej stanowiącej pomnik ofiar niemieckiej okupacji. Mimo częstych aktów wandalizmu udaje się utrzymać prowizoryczny pomnik; zorganizowano tu także przeszło 500 otwartych dyskusji[22]. Plac, który stał się polem walk podczas antyrządowych wystąpień w 2006 roku, gdy u steru byli socjaliści, to także arena jednego z najmocniejszych wystąpień pierwszej edycji oddolnej inicjatywy OFF-Biennale Budapest. The Universal Anthem autorstwa Société Réaliste powstał we współpracy z informatykiem Frédérikiem Mauclèrem, który opracował program obliczający uśredniony zapis muzyczny z plików MIDI – w tym przypadku uśredniony hymn narodowy 193 krajów członkowskich ONZ. Kolektyw założony przez Ferenca Grófa i Jeana-Baptiste’a Naudy’ego, pozostający od 2014 roku „w uśpieniu”, przeplótł ze sobą szerokie spektrum perspektyw i dziedzin – od ergonomii lokalnej i eksperymentalnej ekonomii, przez design, aż po inżynierię społeczną i konsultacje zbiorowe: wszystko to, by lepiej poznać systemy reprezentacji i współczesne ustroje polityczne. Na placu, który ma długą i trudną historię, stanął także pomnik upamiętniający międzywojenną politykę rewizjonistyczną – efekt postanowień pokojowych z 1920 roku w ramach traktatu z Trianon, kończącego formalnie pierwszą wojnę światową, a dziś upamiętnianego Dniem Jedności Narodowej. Jego dziedzictwo do dziś rzuca ponury cień na debaty historyczne i wykorzystywane jest zarówno przez populistyczny rząd, jak i przez propagandę bardziej prawicową. Wieloelementowa instalacja Szabolcsa KissPála From Fake Mountains to Faith – Hungarian Trilogy[23] obiera za punkt wyjścia ten pełen złożoności moment historyczny i zmierza ku nieustannemu zgłębianiu historii politycznej symboliki i oddźwięków przeszłości w propagowanej od niedawna przez państwo mitologii reprezentacyjnej. Projekt złożony z dwóch pokazów wideo w konwencji docu-fiction (Amorous Geography i The Rise of the Fallen Feather) oraz fikcyjnej aranżacji muzealnej (The Chasm Records) przygląda się deformującej mitologizacji początków narodu węgierskiego i politycznemu formowaniu się narodu rozumianego etnicznie, które do dziś jest silnie obecne w retoryce politycznej i zbiorowej wyobraźni. Odbiorcy przedstawiony zostaje ciąg obrazów, przedmiotów i dokumentów odwołujących się do poszczególnych rozdziałów historii nacjonalizmu przez zindywidualizowaną narrację odnoszącą się także do archiwum jako elementu centralnego w artystycznym dochodzeniu prawdy o historii, pamięci, świadectwach i tożsamości.

Société Réaliste, Universal Anthem (2013), performans, OFF-Biennale Budapest, 2015, fot. Zoltán Kerekes, dzięki uprzejmości OFF-Biennale Budapest

KissPál należy, obok Gabrielli Csoszó czy Csaby Nemesa, do niewielkiego grona artystów, którzy zrewidowali swoją praktykę artystyczną w następstwie zaangażowania się w kulturalne i społeczne protesty z lat 2012–2014[24]. Nemes, wykorzystując różne gatunki, systematycznie zgłębia historyczne i bieżące narracje polityczne, zaś Csoszó prowadzi niezależną fotodokumentację w Internecie – jej strona umożliwia wykorzystanie, bez konieczności płacenia tantiem, ale za zgodą autorki, obrazów ważnych wydarzeń społecznych i politycznych, ruchów oraz demonstracji z ostatnich dwóch lat. Część artystów zdecydowało się w ciągu ostatnich trzech–pięciu latach opuścić kraj. Attila Csörgő mieszka obecnie w Polsce, István Csákány w Düsseldorfie, zaś Katarina Sevic, Gergely László czy była kurator główna Ludwig Múzeum Kati Simon – w Berlinie. László, do czasu – wraz z Péterem Rákosim jako Technica Schewiz oraz z Sevic – prawdziwy katalizator węgierskiej sceny, tworzył w Budapeszcie autonomiczne, prowadzone przez artystów centra non profit, takie jak Dinamo, Impex-contemporary art provider, Lumen Grocery czy Community Supplier. Zarówno projekty indywidualne wymienionych, jak i ich przedsięwzięcia grupowe wiązały się z obszernymi badaniami archiwalnymi i stanowią zaproszenie do współpracy, często bazującej na performansie i mającej na celu interpretowanie złożoności konstelacji historycznych. Ich ostatni projekt, zatytułowany Alfred Palestra i po raz pierwszy wystawiony w 2014 roku na biennale w Rennes, pokazano także podczas pierwszej edycji OFF-Biennale w Budapeszcie w 2015 roku oraz na ubiegłorocznej Alternativie w Gdańsku. Opracowano go jako złożone przedsięwzięcie obiektowo-performatywno-książkowe inspirowane niezwykłą historią liceum Émile’a Zoli w Rennes. Szkoła ta to zarazem alma mater pisarza Alfreda Jarry’ego (autora Ubu króla i pioniera francuskiego surrealizmu) i scena drugiego procesu w sprawie Dreyfusa. Centralnym elementem projektu był odczyt performatywny będący efektem warsztatów, do których zaproszono grupę uczniów z liceum Émile’a Zoli. We współpracy z bibliotekami związanymi z oboma historycznymi Alfredami zgłębiali oni kluczowe dla nich zagadnienia: sprawiedliwość, prawdę, edukację, niewolę i nadzieję. Całość przedsięwzięcia opisał László jako „maszynę” działającą jako placówka lub metoda edukacyjna.

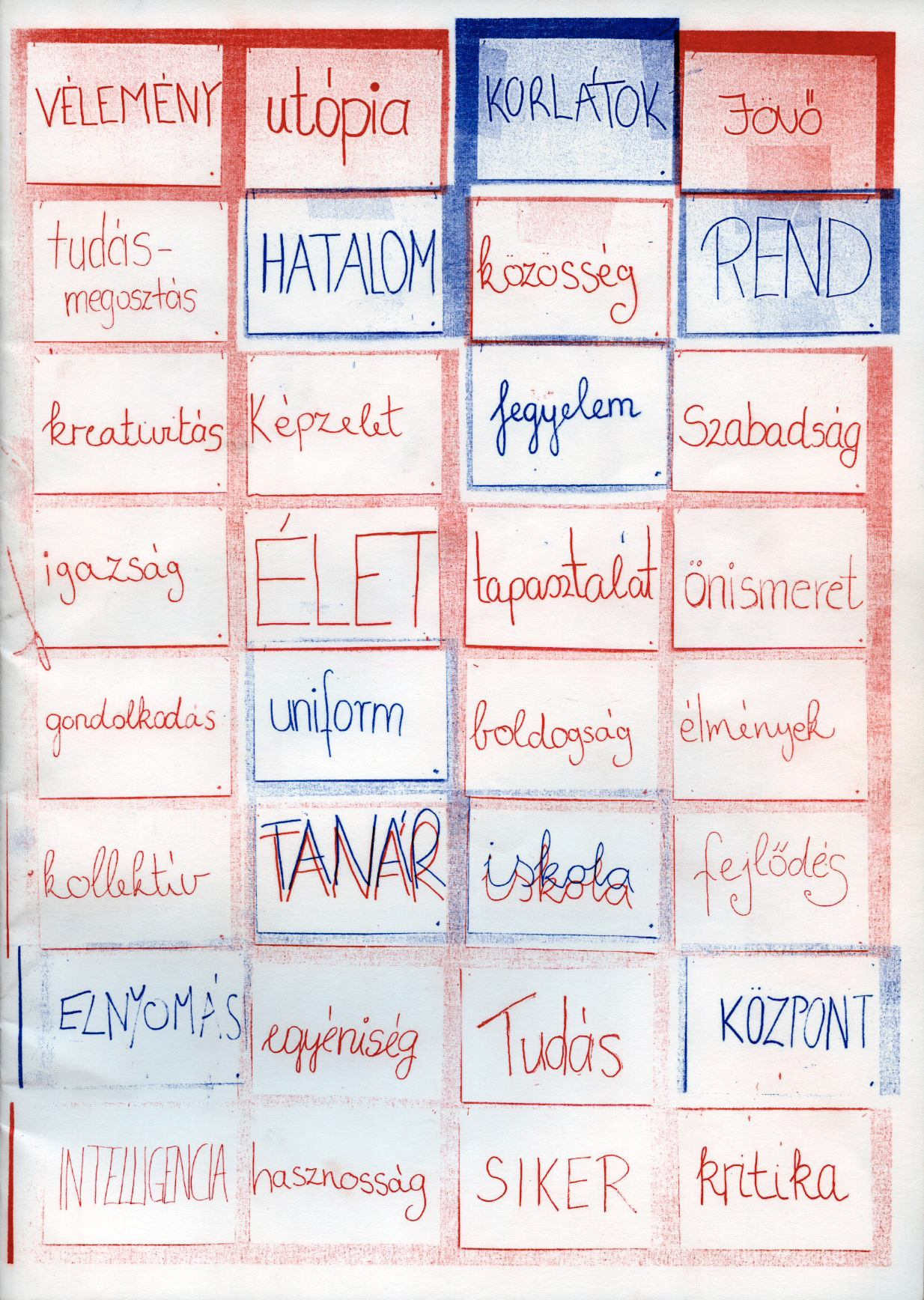

Doświadczenie to ma swój ciąg dalszy w ramach projektu Tanközlöny [Study Gazette], zainicjowanego wspólnie z Virág Major i Emese Váradi na podstawie koncepcji francuskiego pedagoga i reformatora edukacji Celestina Freineta. Współpracując z budapeszteńskimi licealistami, twórcy uruchomili cykl dydaktyczny „Wednesday afternoon”, w ramach którego dyskutowano nad aktualnymi kwestiami dotyczącymi edukacji i przyswajania wiedzy, a także wysuwano propozycje, jaka powinna być szkoła XXI wieku. Było to działanie całkowicie odmienne od rozwiązań narzucanych przez rząd. Efektem projektu, który będzie kontynuowany w obrębie kolejnego OFF-Biennale, było wydanie specjalnej publikacji, dostępnej również w wersji online, stanowiącej krytyczną alternatywę dla podręczników[25].

Okładka publikacji Tanközlöny, 2016, dzięki uprzejmości Tanközlöny

Pojawiło się również o wiele więcej wariantywnych propozycji, strategii i metod opracowanych na lokalnym podwórku mających na celu jednoczenie sceny lub scalanie pomniejszych grup w kolektywne platformy. Narzędziem mają tu być rozwiązania edukacyjne, dyskursywne, akademickie, badawcze bądź zaangażowane społecznie czy oparte na wymianie międzynarodowej[26]. Najambitniejszym bez wątpienia przedsięwzięciem jest w tym kontekście OFF-Biennale Budapest, do którego drugiej, wrześniowej, edycji trwają właśnie przygotowania. Zrodzony z koncepcji kuratorki, dawnej dyrektor galerii Trafó, Hajnalki Somogyi OFF-Biennale, ma w zamyśle stanowić rozbudowaną platformę wymiany oraz wędrowną arenę twórczości. Zaproszono też kilku współpracowników do podjęcia refleksji nad bieżącym globalnym kryzysem, warunkami i szansami pracy w kulturze i produkcji artystycznej oraz do zarysowania kształtu nowej metainstytucji w warunkach niebezpiecznej, represyjnej i moralizatorskiej działalności obecnego reżimu. W ramach swoich możliwości właściwych formatowi biennale, OFF dążyć chce do stworzenia zrównoważonej organizacji o mobilnej infrastrukturze, która chronić będzie autonomiczną działalność, przy jednoczesnym dążeniu do inkubacji nowego ośrodka produkcji. Tematem przewodnim najbliższej edycji będzie historia Gaudiopolis (Miasto radości) – republiki dzieci w powojennych Węgrzech utworzonej przez luterańskiego pastora Gábora Sztehla. Proponowane zagadnienia to: utopia, kryzys, samoorganizacja i międzyrówieśnicze nauczanie. Zapowiadane są projekty zarówno wystawiennicze, jak i edukacyjne oraz mnóstwo wydarzeń towarzyszących, tak w okresie poprzedzającym drugą edycję biennale, jak i po jej zakończeniu pod koniec września.

Mimo dużego zaangażowana w życie artystyczne i społeczne wiele osób rezygnuje z tej sfery działalności na rzecz walki o byt.

OFF-Biennale, którego twórcy liczą na wsparcie zarówno z grantów międzynarodowych i od firm, jak również od prywatnych dobroczyńców, w tym kolekcjonerów mecenasów, takich jak Katalin Spengler-Zsolt Somlói czy Péter Barta, działa w ramach sieci instytucji rynkowych i non profit. Wiele z nich boryka się z niedostatecznym finansowaniem, niedoborem infrastruktury i swoistym samowyzyskiem na wszystkich możliwych poziomach. Mimo swojej bardzo trudnej sytuacji FKSE pozostaje jedną z najstarszych placówek goszczących raczkującą sztukę, oferującą rezydentury i umożliwiających korzystanie z jej wszelkich zasobów. W obrębie swoich pomieszczeń, przy w współpracy z Węgierskim Uniwersytetem Sztuk Pięknych oraz C3, FKSE prowadzi także Labor – niewielką galerię będącą przestrzenią pozwalającą młodym artystom i kuratorom na eksperymentowanie, organizację debat czy przedstawianie prezentacji monograficznych i zbiorowych[27]. Działający non profit Omnivore został uruchomiony przez absolwentów kuratorskich studiów licencjackich, którzy zdobyli już pewne doświadczenia w 2015 roku. Zaprezentowane zostaną także przedsięwzięcia bardziej komercyjne, jak Chimera Project czy Trapéz – udany program poświęcony nowym scenom lokalnym i międzynarodowym, a obok nich uznane już marki, takie jak galerie: Inda, Viltin, Molnar Ani, Erika Deák, art+text czy rezydencki projekt i przestrzeń wystawienniczą Budapest Art Factory. Wśród przestrzeni specjalistycznych pojawią się skupione na sztuce i kulturze Romów Gallery8 i Roma Art Space, organizowane przez zarejestrowaną w roku 2010 Europejską Fundację Kultury Romskiej, a także projekt feministyczny FERi kierowany od października ubiegłego roku przez byłą kuratorkę Ludwig Múzeum Katę Oltai.

Spośród przedsięwzięć przedsiębiorczego młodego pokolenia wspomnieć należy o pięcioosobowym, działającym od roku 2015 kolektywie kuratorskim Teleport[28]. Za punkt wyjścia obrał on próżnię instytucjonalną, chcąc stworzyć migrującą przestrzeń wystawienniczą pociągającą też za sobą różnorodne wydarzenia pozaartystyczne, a także wykorzystującą media społecznościowe, w których przedstawiany jest cykl rozmów zatytułowany Afterwork – seria nieformalnych spotkań z artystami przedstawiany w skrócie w Internecie. Debiut firmowanej przez kolektyw galerii filmów mobilnych Cinema Teleport miał miejsce na jednym z najchętniej odwiedzanych letnich festiwali poświęconych świadomości społecznej, Bánkitó. Program imprezy nawiązuje do aktualnych problemów, takich jak kryzys uchodźczy 2016 roku czy ryzyko korupcji, będące tematem w tegorocznej edycji.

Mimo dużego zaangażowana w życie artystyczne i społeczne wiele osób rezygnuje z tej sfery działalności na rzecz walki o byt. Warto tu przytoczyć niedawną obserwację członkini zespołu kuratorskiego OFF-Biennale Nikolett Erőss: „To wstrząsające, że młodsze pokolenia nie pamiętają nawet «normalnego» funkcjonowania instytucji; skromne i niepewne obecne warunki stały się dla nich paradygmatem. Niewielu narzeka, ale trudno też o zdolność i potrzebę myślenia długoterminowego i osadzonego w kontekstach historycznych”[29]. Wyzwanie jest jednak znacznie bardziej złożone i naglące – chodzi o coś więcej niż zapewnienie przestrzeni wystawienniczej przy jednoczesnym zrównoważonym i zauważalnym publicznie działaniu krytycznej kultury współczesnej. Kluczowa i nieunikniona jest konfrontacja sektora sztuki z zagadnieniem własnej publiczno-instytucjonalnej odpowiedzialności; przemyślenie tego, w jaki sposób ma on wypełniać swoją socjokrytyczną funkcję, przy jednoczesnym zaproponowaniu wizji kultury i polityki obejmującej racjonalne działania, odzyskanie instytucji i prawo do podejmowania autonomicznej, gwarantowanej przez państwo działalności. Zredefiniowanie tego, co publiczne, to zadanie wymagające aktywności, które musi stanowić komponent zorganizowanego oporu politycznego. Nie pozostaje mi nic innego, niż zgodzić się z Árpádem Schillingiem – teraz nie mamy już wyboru.

tłumaczenie: Stanisław Bończyk

Tekst powstał w lutym 2017 roku, zaś w lipcu – między zleceniami realizowanymi w Szwecji i Irlandii – został zaktualizowany. Nie ma on stanowić wyczerpującej analizy, lecz raczej zwięzłe i w nieunikniony sposób fragmentaryczne sprawozdanie na temat warunków, w jakich funkcjonuje budapeszteńska scena krytyczna.

Autorka pragnie podziękować Ágnes Berecz, Nikolett Erőss, Zsófii Frazon i Natashy Schastnevej za pomoc i wnikliwe komentarze.

Tekst ukazał się w 18. numerze Magazynu „Szum”.

[1] Azt kéne mondanom: végem vani [I Should Say This Is the End of Me], rozmowę przeprowadziła Andrea Tompa „Magyar Narancs” 2015, nr 8,. Tekst wyłącznie w wersji węgierskiej: http://magyarnarancs.hu/szinhaz2/azt-kene-mondanom-vegem-van-93815/?orderdir=novekvo [dostęp: 7.07.2017] [ze względu na publikację w magazynie drukowanym tekst został skrócony o przypisy zawierające wyłącznie odnośniki do stron internetowych instytucji bądź inicjatyw artystycznych – przyp. red.].

[2] Przyznanie w 2016 roku prestiżowej Nagrody im. Księżniczki Margriet stanowiło dowód uznania wobec kulturalnego i edukacyjnego zaangażowania Krétaköra, w szczególności zaś otwarcia w 2013 roku Free School – Wolnej Akademii, http://kretakor.eu/post-en/freeschool-the-first-3-years/ [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[3] Fundacja Warsztatów Krétakör, która z powodu braku finansowania zakończyła działalność w 2016 roku, uchodzi za wzór w obrębie sektora non profit. „Należy być zdeterminowanym, gdy idzie o własne ideały artystyczne, i uczestniczyć w międzynarodowych sieciach i formach współpracy, by znaleźć finansowanie dla jakościowej sztuki. Krétakör i Fundacja Warsztatów stanowią przykład tego, jak można zrobić coś z niczego. Problem w tym, że tego rodzaju drobne inicjatywy tworzone w sektorze non profit nie są w obecnym systemie finansowania kultury zachęcane, by ubiegać się o finansowanie na poziomie samorządowym lub ogólnokrajowym. W efekcie głosy niezależne i krytyczne są w ostatecznym rozrachunku mocno ograniczane”, https://www.boell.de/en/2014/12/29/theatre-financing-and-independent-theatre-scene [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[4] Wersja wyłącznie węgierska: http://hvg.hu/kultura/20170405_schilling_arpad_nemzeti_konzultacio_video [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[5] Analiz sytuacji polityczno-kulturalnych na Węgrzech w ostatnim okresie dokonywali były dyrektor Ludwig Múzeum w Budapeszcie, Barnabás Bencsik, polski kurator i krytyk Stach Szabłowski oraz uczestnicy dwudniowego sympozjum „Perfect Harmony” w Atenach – konferencji, podczas której dzielono się uwagami na temat dotyczących Europy Środkowej problemów w kwestiach sztuki, aktywizmu i polityki. Warto także wspomnieć o konferencji „House of Cards and What to Do about It: Institutions Today”, która odbyła się w Zagrzebiu w lipcu 2016 roku, do której ja również dołożyłam swoją cegiełkę w postaci prezentacji. W okresie późniejszym powstały artykuły kurator Eszter Szakács oraz artystki i socjolożki Ágnes Básthy. Zarys konferencji w Atenach znajdziemy w: Tereza Papamichali, Perfect Harmony. Recent Art and Politics in Eastern Europe, http://magazynszum.pl/krytyka/transitions-3-symposium-perfect-harmony-recent-art-and-politics-in-eastern-europe [dostęp: 7.07.2017]; Edit András, Hungary in Focus: Conservative Politics and Its Impact on the Arts. A Forum, „Artmargins”, 17.09.2013, http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/interviews-sp-837925570/721-hungary-in-focus-forum [dostęp: 7.07.2017]; Barnabás Bencsik, The Captured Institutions of an Art Scene: Hegemonic Tendencies in Hungarian Cultural Politics since 2010, [w:] Art and the F Word. Reflections on the Browning of Europe, ed. Maria Lind, What, How & for Whom/WHW, Sternberg Press–WHW, Zagreb–Tensta Konsthall, Stockholm 2014, http://www.sternberg-press.com/?pageId=1530 [dostęp: 7.07.2017]; tekst autorstwa Stacha Szabłowskiego dostępny pod adresem: http://www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/6548-po-prostu-nas-wysmiali.html [dostęp: 7.07.2017]; informacje o konferencji w Zagrzebiu: http://www.thisistomorrow.org/activities/house-of-cards-and-what-to-do-about-it-art-institutions-today/ [dostęp: 7.07.2017]; Eszter Szakács, The Unofficial Art and Positive Forms of Resistance Today in Hungary, ICI, 2016 http://curatorsintl.org/research/unofficial-art-and-positive-forms-of-resistance-today-in-hungary [dostęp: 7.07.2017]; Ágnes Básthy, What Can Be Said About The State of Hungarian Art?, „Political Critique”, 15.03.2017, http://politicalcritique.org/cee/hungary/2017/hungary-art-protest-culture/ [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[6] Więcej: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/23/67801/back-to-the-future-report-from-hungary/ [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[7] Węgierska Akademia Sztuki powstała w 1992 roku, zrzeszając 22 prawicowych artystów węgierskich, w zamyśle miała stanowić przeciwwagę dla niezależnej Akademii Literatury i Sztuki Węgierskiej Akademii Nauk. Cieszący się wątpliwą – sięgającą czasów socjalistycznego reżimu – reputacją dyrektor instytucji, projektant wnętrz György Fekete, może, korzystając ze wsparcia ministra zasobów ludzkich Zoltana Baloga, otwarcie realizować swój cel, którym jest „stawanie w kontrze wobec tendencji liberalnych we współczesnych sztukach pięknych”, a zarazem tworzenie linearnej historii sztuki opartej na kulturze chrześcijańskiej i tradycyjnych wartościach narodowych mających „wzmacniać poczucie szczęścia w węgierskim społeczeństwie”. We wrześniu ubiegłego roku wyglądało na to, że HAA zwieńczyła proces zawłaszczania instytucjonalnego po tym, jak otrzymała pełnię praw do zarządzania jedną z największych węgierskich instytucji sektora sztuki – budapeszteńską Pałacem Sztuki (wraz z prawami do trzech innych kluczowych gmachów i instytucji kultury). Począwszy od listopada 2015 roku, HAA posiada uprawnienia zarówno do delegowania 1/3 członków-kuratorów do departamentów Węgierskiego Narodowego Funduszu Kultury (nadrzędnej instytucji odpowiadającej od 20 lat za finansowanie działalności kulturalnej na terenie Węgier i poza ich granicami, utrzymywanej w 90% z podatku od hazardu i loterii), jak i do nadzorowania działalności kuratorskiej. Oznacza to, że niechybnie będzie brać udział w procesie dystrybucji środków.

[8] Więcej: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/06/hungary-ngo-law-a-vicious-and-calculated-assault-on-civil-society/ oraz: http://www.pen-international.org/newsitems/hungary-new-ngo-law-will-have-chilling-effect-on-freedom-of-expression/?print=print [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[9] Przegłosowując Lex CEU, parlament węgierski dążył do wyjęcia spod prawa Uniwersytetu Środkowoeuropejskiego w Budapeszcie. Spotkało się to z wielkim sprzeciwem zarówno na Węgrzech, jak i za granicą, ponieważ postrzegano tę nowelę jako kolejny krok ku osłabieniu niezależności szkół wyższych. Więcej: https://www.boell.de/en/2017/06/27/hungary-lex-ceu-kafkaesque-affair [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[10] Młody – łączący liberalizm z konserwatyzmem – ruch polityczny Momentum szybko mógł przerodzić się w partię. Znaczny odsetek jego członków, których wciąż przybywa, studiowało lub mieszkało za granicą. Są to osoby gotowe stosować najlepsze, spotykane na całym świecie praktyki, a zarazem niezamierzające wdawać się w utarczki ideologiczne i drobne spory frakcyjne. Pierwszą inicjatywą polityczną ruchu była kampania NOlimpia. http://hungarianspectrum.org/2017/01/18/another-attempt-to-change-the-political-landscape-the-momentum-movement/ [dostęp: 2.07.2017]; https://www.boell.de/en/2017/04/11/momentum-movement-there-bright-future-new-hungarian-youth-party [dostęp: 2.07.2017].

[11] Od 2015 roku Márton Gulyás prowadzi SLEJM, wideobloga poświęconego polityce: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEFpEvuosfPGlV1VyUF6QOA [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[12] Zdecydowałam się skupić uwagę na sztuce współczesnej, dlatego też mój artykuł daje wyłącznie ogólny obraz sytuacji, bez wchodzenia w szczegóły dotyczące aspektów szkolnictwa wyższego, muzealnictwa, literatury i tak dalej.

[13] W tym gronie znajduje się także ciężko doświadczone, pozbawione ekspozycji Węgierskie Muzeum Architektury, którego zbiory od dawna tkwią w magazynach. Stanie się ono teraz częścią wszechwładnego publicznego ciała, jakim jest Węgierska Akademia Sztuki.

[14] Decyzje władz zawierają wiele nakazów i przekształceń służących politycznej centralizacji i kontroli także przez wprowadzanie zmian w ministerstwach, w tym zarządzanie sektorem dziedzictwa narodowego, doprowadzenie do swobodnego przemieszczania artefaktów, fuzję Muzeum Sztuk Pięknych i Węgierskiej Galerii Narodowej, „królewsko-rządowe” przejęcie terenów dzielnicy Zamkowej (Várnegyed) oraz wielce ambitny Hauszmannowski plan rekonstrukcji Zamku Królewskiego (przy sporym dofinansowaniu ze strony UE) czy równie megalomański i wysoce nieprzejrzysty pomysł dotyczący Liget Budapest Projekt.

[15] Jedną z najdroższych takich inicjatyw jest odnowiony i dwukrotnie otwarty w roku 2014 Várkert bazár, pawilon w Ogrodach Zamkowych goszczący również KOGART, finansowaną przez państwo kolekcję prywatną, http://www.varkertbazar.hu/en/history [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[16]Kultpol 2016 – Megy mint a karikacsapás… [Cultural Politics 2016 – Goes like clockwork…], ed. Gergely Nagy, „Műértő” 2017, nr z lutego, s. 7.

[17] Więcej: http://creativetimereports.org/2015/06/22/off-biennale-breaking-off-an-interview-with-the-organizers-of-a-new-grassroots-biennale-in-budapest/ [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[18] Maja Reuben Fowkes, Placing Bookmarks: The Institutionalisation and De-Institutionalisation of Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde and Contemporary Art, „Tate Papers” 2016, No. 26, Autumn, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/26/placing-bookmarks [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[19] Jeden z ostatnich artykułów na ten temat ukazał się w niezależnym internetowym magazynie „Kettös Mérce” wyłącznie w wersji węgierskiej: http://kettosmerce.blog.hu/2017/03/24/kis_mozgalomtortenet_a_magyar_kepzomuveszet_helyzete [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[20] Państwo znacjonalizowało przechowywane w placówce dokumenty archiwalne z lat 1944–1989, a także podjęło próbę przejęcia budynku, którym instytucja zarządza od 1957 roku. Dawne mieszkanie Györgya Lukácsa służy jako archiwum, przestrzeń badawcza oraz biblioteka od czasu śmierci filozofa w 1971 roku. Lukács zapisał swoją bibliotekę i dokumenty Węgierskiej Akademii Nauk. 28 marca z parku św. Stefana w budapeszteńskiej XIII dzielnicy usunięto pomnik tego uznanego marksistowskiego filozofa. Rzeźbę zamówiła Węgierska Akademia Nauk, a wykonał ją w 1985 roku Imre Varga.

[21] Słowa teoretyka Pétera Györgya, A Fidesz az amnézia pártján van [The Fidesz Party Sides with Amnesia], rozmawiał György Vári, „Magyar Narancs”, 7.11.2013, http://magyarnarancs.hu/belpol/a-fidesz-az-amnezia-partjan-van-87316 [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[22] Zob. http://hungarianspectrum.org/2014/01/24/krisztian-ungvary-on-the-memorial-to-the-german-occupation-of-hungary-the-living-horror/ [dostęp: 7.07.2017]. Więcej na temat działalności The Living Memorial: http://www.silentheroes.eu/attachments/02/04_01/LivingMemorial_PRESS.pdf, http://artycok.tv/en/27810/living-memorial oraz: http://hungarianfreepress.com/2016/08/15/budapest-living-memorial-an-interview-with-eszter-garai-edler-and-balazs-horvath/ [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[23] Szabolcs KissPál, którego praktyka artystyczna opiera się na wykorzystywaniu nowych mediów, sztuk wizualnych i problemów społecznych, od 2012 roku uczestniczy w różnych projektach aktywistycznych, takich jak oprotesotowanie muzeów czy akty obywatelskiego nieposłuszeństwa, jak noMMA czy „The City Is for All”. From Fake Mountains (…) powstało przy wsparciu Stipendium für Medienkunst Edith Russ Haus oraz Stiftung Niedersachsen. Po raz pierwszy wystawiono je w roku 2016 w ramach wystawy Building Nations. Amorous Geography stanowiło element projektu Zoo-topia, ed. Eszter Steierhoffer, HCC, 2012. Więcej: Edit András, They Are So Very Different From Us, „Eurozine” 2015, lipiec, http://www.eurozine.com/they-are-so-very-different-from-us/ [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[24] Pogłębiona analiza Edit András dostępna tutaj: http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/interviews-sp-837925570/721-hungary-in-focus-forum [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[25] Zob. Tanközlöny online (tylko wersja węgierska): https://issuu.com/tankozlony/docs/tankozlony [dostęp: 7.07.2017]. Celem uruchomienia badań prowadzonych przez grupy uczniów liceum Frigyes Karinthy nie było stworzenia publikacji, ale właśnie samo działanie grupy badawczej, które pozwoliło młodym ludziom myśleć w sposób niezależny i uczyć się demokratycznego dyskutowania na temat złożonych kwestii związanych z edukacją.

[26] Za przykład posłużyć tu mogą wspólnotowy pub-kawiarnia Gólya i Jurányi House. http://golyapresszo.hu/?lang=en_us [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[27] LABOR powstał we wrześniu 2007 roku jako wspólna inicjatywa Kulturális és Kommunikációs Központ Alapítvány C³ [Fundacja Centrum Kultury i Komunikacji C³], FKSE oraz MKE – w miejsce dawnej galerii Stúdió. W latach 2009–2011 do współpracy został włączony program sztuki współczesnej Tranzit.hu.

[28] Członkowie kolektywu to: Tamás Don, Flóra Gadó, Bea Istvánkó (do początku 2017 roku), Ferenc Margl i Vanda Sárai, http://teleportgaleria.tumblr.com/ [dostęp: 7.07.2017].

[29] Cytat z rozmowy z autorką, luty 2017.

ENG

Fear Eats the Soul: A Partial Report on Hungarian Contemporary Culture

It has already been two years since the internationally acclaimed theater director and activist Árpád Schilling bitterly stated in an interview: “The consensus that in some ways kept Hungarian society and the political elite together is over. We’ve fallen apart.”[1]

It came right after the premiere of Loser (2015),[2] in which the founding director of Krétakör pushed numerous societal pressure points and presented himself as a model of the angry and radicalizing intellectual who performs the unresolvable conflict of combining uncompromisingly critical political engagement and autonomous artistic expression. Schilling’s diagnosis of the current state of affairs is based on his more than twenty years of critically engaged theater and community building through which he publically addresses anomalies within culture and politics, which in 2016 won Krétakör the prestigious Princess Margriet Award.[3] Krétakör’s decision to stop producing “traditional” performances in 2008 points to a changed perspective on agency, which posits art should be employed to effect change through breaking the fourth wall and uniting political theater and drama-pedagogical methods while building a critical audience.[4] Many, within and beyond the fields of culture, were confronted by the dilemmas Loser presented, especially those who see the arts as a complex cultural, educational, and socially and politically engaged medium within an increasingly undemocratic state operation. In April 2017, Schilling published an edgy video manifesto in which he, dressed in boxer shorts, provided a direct response to the Hungarian government’s recent “Let’s Stop Brussels” national consultation questionnaire, yet another in a long line of manipulative self-justifying campaigns.[5] His unrelenting anger, as shared in recent interviews, calls for civil disobedience and the non-acceptance of excuses to avoid active participation in the anti-governmental struggle.

The government-decreed mandates and licenses resulted in the HAA functioning as a shadow ministry, and the sole authority that decides upon and administers public duties related to the arts and culture in Hungary.

Altough the current crisis has a complex history, the most urgent issues facing the contemporary culture sector are a direct consequence of the grievously corrupt, destructive politics and ideological campaign of the current regime.[6] Following the Fidesz’s gradual takeover of national media, the last decades’ hard-won positive shifts and progressive changes within contemporary culture were quickly dismantled, followed by anti-intellectual attacks to discredit inconvenient critical voices and media narratives.[7] By 2011–12, not only had the economic situation become harder for most state- and civic-funded institutions and independent organizations, but the ultra-conservative, nationalist Hungarian Academy of Art (HAA)[8] was legally elevated to the status of “public benefit organization” within the new constitution. The HAA has since been stuffed with public money—as have the government-organized non-governmental organizations and media as well as the institutions run by loyal dilettanti—and has taken over often significant cultural venues such as Műcsarnok – Kunsthalle Budapest. The government-decreed mandates and licenses resulted in the HAA functioning as a shadow ministry, and the sole authority that decides upon and administers public duties related to the arts and culture in Hungary—including literature, music, fine art, applied art, design, and architecture, as well as theory, education, and the national and international presentation and representation of artists. No arm’s-length principle is applied to public affairs. Directorial appointments are largely based on nepotism and political sympathies for the ruling party. Job succession in the cultural field happens seemingly without a need to match the professional criteria and vision of predecessors. Serving its politics of centralization and control via ministerial departments, the government’s decisions about numerous restructurings within the museum, cultural, heritage, and academic sectors, as well as the national archives, painfully lack the required minimum of professional debate or understanding of practical necessities.

In 2017, the political and social crisis has become further aggravated. The deepening anti- immigration and anti-EU rhetoric is accompanied by its related media witch-hunt and billboard campaigns, further trespass on minority rights, social benefit cuts, and the crumbling state of education and health care, along with the expansive war on internationally funded NGOs and institutions, labelling them as threats to the country and recently resulting in a new, highly criticized NGO law[9] (echoing Russia’s “anti–foreign agent” law introduced in July 2012), and the highly controversial Lex CEU amendment, which targets not only the transnational private Central European University (founded in 1991 and moved to Budapest in 1993) but also the Hungarian American billionaire George Soros, whose Open Society Foundations supports several NGOs and other non-governmental projects.[10] Within the deepening media crackdown, small alternative hubs are also being targeted, such as the thriving independent leftist activist and community center Auróra, which houses eight NGOs that focus on marginalized and stigmatized groups and also hosts readings, discussions, and cultural programs.[11] Within a system characterized by expanding institutionalized corruption, widening social inequality, and increasing intimidation of public employees—all embedded in continuous cynicism and hate-mongering—the satirical poster campaigns of the Two-Tailed Dog Party,[12] a grassroots activist group that uses absurd humor as a political weapon, and the appearance of new political groups such as Momentum[13] and Common Country[14] (the latter founded by activist, blogger, and former Krétakör executive manager Márton Gulyás[15]) signal an intensifying need for a changed and responsible attitude, language, and rhetoric within the culture and operation of politics.

Many professionals are confronted with hard choices when trying to maintain pockets of professional independence and internationally and regionally informed operation within contemporary art, culture, and museology.[16] In Hungary, the renunciation of (good) governance—or rather, the almost complete divorce from responsible democratic operation—has further eroded the public cultural institution/museum and publishing systems. By the end of 2016, five state-financed institutions dealing with museums, heritage protection, and cultural education, including the Hungarian National Digital Archive (MaNDA), had been shut down for “reorganization.”[17] Some of these had already undergone refashioning by the current regime. The systematic and ideology-driven taking over and remote controlling of institutions, the lack of structural and programming autonomy, and a neo-feudalist system where cultural heritage is understood in relation to a politically reinvented national identity crowned by arrogant anti-professionalism that further hinders essential institutional changes.[18] As many public museums struggle financially in Budapest—and the situation outside the capital is even more precarious—both temporary and lasting representational spaces managed by business investment groups and served by selected court-curators and advisors have opened to host historical and contemporary cultural projects.[19] The system of anniversary-focused bursaries contributes to the hindrance of long-term professional planning while strengthening dependence on politically driven agendas, implicating institutions in often manipulative government narratives.

Launched in 2015, the grassroots curatorial initiative OFF-Biennale Budapest has declared the project independent from state funding and stated its intention to steer clear of state-run art venues.

In a recent survey of art professionals by the art monthly Műértő, art historian and critic Edit András pointed at the state’s tactics of addressing various branches of culture separately through transformative measures, and thus they may feel the weight of government intervention only at their sectoral proximity.[20] Eszter Kozma, a curator and head of the Studio of Young Artists’ Association (SYAA/FKSE), stressed how the “restructuring” of the institutional system has brought not only existential and professional crises, but a series of moral (and I would add deepening and dividing) dilemmas, one of which is a question of whether to take part in the biased grant system and its corrupted fund distribution. FKSE published a manifesto at the end of 2012 stating its withdrawal from the curatorial board of the National Cultural Fund of Hungary and decision to suspend funding applications due to the body’s corrupted operations.[21] As centralized state funding continues to determine the Hungarian art system, the progressive and critically engaged sectors struggle to maintain their institutions, international visibility, and networks of production. The limited prospect of multipronged strategies, a still weak local art market, and a shrinking donor base have pressured a considerable number of artists and cultural workers to either give up their practice or, as in the case of various artistic and curatorial initiatives, undertake an overwhelming amount of pro bono and self-exploitative work.

Launched in 2015, the grassroots curatorial initiative OFF-Biennale Budapest has declared the project independent from state funding and stated its intention to steer clear of state-run art venues.[22] But what is also at stake here, and what is becoming central not only for OFF but also for other projects sustaining a critical practice within the institutional system, is how to reinstate the “publicness” of the public institutional infrastructure and resources and ensure a democratic and autonomous operation with the arm’s-length principle applied. Many of the more established artists and curators, as well as those who are freshly out of academies, find themselves in a vacuum within the highly polarized cultural environment, where one is pretty much left to navigate only within the small circle of private donors, collectors, and gallerists—some of which have pronounced or less transparent links to state interests.

While former key institutions such as Kunsthalle Budapest have been more or less wiped off the critical visual art map, the Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art—though without the former directorship’s consistent and strategic programming, staff, and long-term research engagement—still presents a relatively active schedule of modern and contemporary art, such as the traveling The Wild West. A History of Wroclaw’s Avant-Garde, Atilla Szűcs’s 2017 mid-career retrospective Specters and Experiments, and a recent show on the neo-avant-garde movement of the Pécs Workshop.

Among those who sooner or later left Budapest’s Ludwig Museum after the controversial change of directors in 2013, some, including art historian Emese Kürti and curator Róna Kopecky, continued their work and research within the for-profit sphere. Kopeczky became the artistic co-director of acb Gallery, but has also for four years co-run Easttopics, a non-profit online project dedicated to the promotion of Eastern European contemporary art.[23] Art historian, OFF curator, and former Ludwig curator Katalin Székely, who works as a creative program officer at Open Society Archives,[24] served as editor of the publication that accompanied Bookmarks, a project supported by collectors and prominent galleries. The exhibition, which debuted at Art Cologne in 2015, surveyed the most significant positions in Hungarian neo-avant-garde and post-conceptual art from the late 1960s to the present, with artists such as Dóra Maurer, Tamás Szentjóby, Little Warsaw, and Gyula Várnai, who also exhibited in the Hungarian Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale.[25] A kind of follow-up in the United States, though featuring a different selection of artists, was hosted by the Elisabeth Dee Gallery in New York in May–August 2017.[26]

Within Hungary’s institutional-professional breakdown, a significant portion of the research on the cultural and artistic legacy of the state socialist period (under the Kádár regime) has been largely taken over by the for-profit sector, including acb Gallery’s ResearchLab, founded in September 2015.[27] Led by Emese Kürti, ResearchLab’s mandate includes international publishing and monographic presentations of Hungarian neo- and post-avant-garde practices, such as that of the poet and performer Katalin Ladik, who was recently featured at documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel.[28] Concerns have been expressed as to whether the market-driven representation, as well as the modest capacities of the for-profit galleries, may result in the partial disappearance of some of the artistic legacies of the Hungarian Cold War period (and soon also the 1990s), as the path to entering the canon via institutionally sustained, complex art- and social-historical research and critical presentation has been set back.[29]

There are, however, still spaces within the public museum system to operate critically. One of the most inarguably relevant of these is the Kassák Museum, where its director, the art historian Edit Sasvári, has being building an internationally acknowledged museum program with her team since 2010. Based on the literary, publishing, and visual arts heritage of the modernist painter, writer, publisher, and public intermediary Lajos Kassák, the former reservoir has become a hub for young scholars and historians who cross-examine this rich legacy within social and political history. The Kassák’s long-term research-based project Life Reform and Social Movements in Modernity, which began in 2012, provides “space for presenting socially sensitive subjects and artistic projects.” In 2014, the museum launched a multiyear research project on visual art in the 1960s and ’70s that proposes “a new conception that focuses on the regional context, replacing both the isolated nationalist view and the centre-periphery dichotomy.”[30] Among the few who actively strengthen dialogue between disciplines is museologist and critic Zsófia Frazon, who has initiated various projects and research to open up the Ethnographic Museum to the present and the systematic analysis of contemporary culture and who has also contributed to the Curatorial Dictionary project run by curator Eszter Szakács at tranzit.hu.[31] Despite ongoing difficulties, the Hungarian University of Fine Arts successfully launched a BA in Fine Art Theory in September 2009, established the Department of Art Theory in 2010, and has devised the currently pending MA in Contemporary Art Theory and Curatorial Studies.[32] Their graduate program has given space to significant stopgap research on recent art history.

There are also models within the state-independent scene, such as the contemporary art program tranzit.hu and the independent curatorial duo Maja and Reuben Fowkes, who facilitate international exchange and promote the local scene through their networks. The Fowkes’ curatorial program, under the name the Translocal Institute since 2013, has bridged academic and curatorial discourses through maintaining a strong position on sustainability, ecology, and the anthropocene, and has engaged in long-term research on the Eastern European neo-avant-garde.[33] Tranzit.hu, which is currently transforming and has moved office locations, has embraced a great number of different approaches, from its free school series and cultural blog to more activist-based projects such as the Action Day series, the Catalyst Award given for progressive cultural initiatives, and the recently launched international online art and culture magazine Mezosfera.[34]

Rare is the situation where an art space can experience more or less undisturbed operation and build a consistent program. One such lucky exception is the state- and city-funded Trafó Gallery (part of Trafo House of Contemporary Arts), where curators Áron Fenyvesi and Borbála Szalai (the latter also a member of the OFF Biennale curatorial team focus) on a variety of conceptualist, performative, and post-abstract practices both locally and from the Visegrad region.[35]

The most dramatic episode in the continuous memory-political-representational battle and the current government’s “state of amnesia policy” remains Liberty Square, where the Budapest-based activist group Living Memorial formed in April 2014 in protest against the much criticized sculptural installation of a memorial to the German occupation.

But the last five years have also painfully pointed out the more apparent deficits of the decades following the regime change in 1989 and how little space is left, physically and intellectually, for facing the controversies and complexities of the histories and the intellectual and political legacies of the last century. It’s enough to look at the pending future of the Institute of Political History, or the grappling within the Hungarian Academy of Sciences about the status and future of the Georg Lukács Archives. Packaged as mostly administrative necessities, government measures threaten a indefinite suspension of research access and facilities, and also the unprofessional treatment, isolation, and tucking away of sensitive legacies.[36] The recent removal of Lukács’s statue in Budapest is one of the government’s many rearrangements to streamline the urban environment and its approach to historical commemoration.

The most dramatic episode in the continuous memory-political-representational battle and the current government’s “state of amnesia policy”[37] remains Liberty Square, where the Budapest-based activist group Living Memorial formed in April 2014 in protest against the much criticized sculptural installation of a memorial to the German occupation. Despite occasional vandalization, the group keeps up a spontaneous anti-memorial and has organized more than five hundred open discussions so far.[38] The square also provided space for one of the strongest performances within the first edition of OFF-Biennale Budapest in 2015. Société Réaliste’s Universal Anthem, made in collaboration with computer engineer Frédéric Mauclère, who developed software that calculates average musical notations in MIDI files, presents the average national anthem of the 193 member states of the United Nations.[39] The artist cooperative, which was founded by Ferenc Gróf and Jean-Baptiste Naudy in 2004 and has been on hiatus since 2014, has intertwined a broad range of perspectives and fields, from territorial ergonomics, experimental economy, and design, to social engineering and consulting, to investigate systems of representation and contemporary systems of politics.

Katarina Šević / Tehnica Schweiz, Alfred Palestra, performance, “PLAY TIME”, Lycée Émile Zola, Rennes, France, 2014, photo: Aurélien Mole, courtesy of the artists

During its complex history, Liberty Square once housed a four-part monument to the interwar years’ revisionist politics—the result of the Treaty of Trianon peace agreement to formally end World War I in 1920. Remembered officially by the Day of National Unity, the Trianon legacy casts a bitterly dark shadow on historical debates and has been exploited by both populist governmental and more right-wing propaganda. Szabolcs KissPál’s multi-piece installation From Fake Mountains to Faith (Hungarian Trilogy) (2016)[40] departs from this complex historical event and is based on an ongoing inquiry into the history of political symbolism and the reverberations of the past in recent state representational mythology. The project, which consists of two docufiction videos (Amorous Geography, 2012, and The Rise of the Fallen Feather, 2016) and a fictitious museum setting (The Chasm Records, 2016), looks at the distorted mythologization of the origins of the Hungarian nation and the political formation of the ethnic nation that continues to occupy a significant portion of political speech and imagination. A nexus of images, objects, and documents invites the viewer to trace specific chapters of the history of nationalism through a personalized narrative, which also alludes to the archive as central in artistic investigations of history, memory, testimony, and identity.

Szabolcs KissPál, The Chasm Records, 2016, installation view at Edith-Russ-Haus für Medienkunst, Oldenburg, Germany, photo: Carina Blum, courtesy of the artist

KissPál is one of a small group of artists who, similar to Gabriella Csoszó and Csaba Nemes, have revised their artistic practices following their active involvement within the cultural and social protests that took place between 2012 and ’14.[41] While Nemes, who works in different genres, systematically investigates historical and current political narratives, Csoszó runs an independent photodocumentary site that offers royalty-free but author-permitted images of important social and political events, movements, and demonstrations from the past two years.[42] In parallel to KissPál, Csoszó, and Nemes, quite a few artists and professionals have alternately opted to leave the country for various reasons over the last three to five years. Attila Csörgő now lives and works in Poland, István Csákány in Dusseldorf, and Katarina Šević, Gergely László, and former Ludwig Museum chief curator Kati Simon are all based in Berlin. László (who together with Péter Rákosi works as Tehnica Schweiz) and Šević were catalysts in the setting up of autonomous, non-profit, artist-run spaces in Budapest such as Dinamo, IMPEX – Contemporary Art Provider, and Lumen Grocery & Community Supplier.[43] Both artists’ individual and group projects engage in extensive (archival) research and propose collaborative, often performance-based works that explore how to interpret complex historical constellations. One of Šević and Tehnica Schweiz’s most recent projects, Alfred Palestra[44]—produced in 2014 for PLAY TIME / Work as Play, Art as Thought, the fourth edition of the biennial Les ateliers de Rennes, and subsequently shown at the 2015 OFF-Biennale Budapest as well as the 2016 Alternativa in Gdańsk—developed as a complex object, performance, and book project inspired by the remarkable history of the Lycée Émile-Zola in Rennes, a school that is both the alma mater of writer Alfred Jarry (writer of Ubu Roi and pioneer of French surrealism) and the site of the second trial of the Dreyfus affair. Central to the piece is a reading performance that resulted from a workshop with a group of high school students from the Lycée Émile-Zola, who worked with the libraries[45] connected to the two Alfreds and key themes such as justice, truth, freedom, education, captivity, and hope. László describes the work as a “machine” that operates as an educational facility or method.

The experience lives on within the project Tanközlöny (Study gazette, 2016), which László initiated together with Virág Major and Emese Váradi and is based on the concepts of French pedagogue and educational reformer Celestin Freinet. They launched the study program Wednesday Afternoon with Budapest high school students, during which they discussed topical questions surrounding education and learning as well as made proposals for what the twenty-first-century school should look like—something entirely different from what government policies push on education. The project is accompanied by a printed and online publication, conceived as a critical textbook alternative, and will continue in the framework of the next OFF-Biennale.[46]

There have also been many other alternative proposals, strategies, and practices developed locally that aim at bringing the critical sectors of the Hungarian contemporary art scene, and smaller groups within, into collective platforms through educational, discursive, academic, research-based, and other more socially engaged strategies while trying to provide frameworks of production and international exchange.[47] Unquestionably, the most ambitious of these undertakings has been OFF-Biennale Budapest, the second edition of which opened in late September 2017. As conceptualized by curator and former director of Trafó Gallery Hajnalka Somogyi, OFF has been imagined as an expanded platform of exchange and nomadic site of production. It has invited several collaborators to critically reflect on diverse aspects of the current global crises in order to consider the conditions and possibilities of cultural work and artistic production and to draft a new meta-institution within the current regime’s hazardous, policing, and moralizing operation. Within its capacities to appropriate the biennial format, OFF has the aim to set up a sustainable organization with mobile infrastructure that protects autonomous operation while incubating a new production center. The second edition’s thematic umbrella is the (his)story of Gaudiopolis (The City of Joy), which was a children’s republic in Hungary during the postwar years led by the Lutheran pastor Gábor Sztehlo. The proposed direction of inquiry expands to questions of utopia and crisis, self-organization, and peer-to-peer education and presents prognoses of both exhibition and educational projects, including a number of accompanying events that led up to and may follow the second OFF-Biennale.[48] OFF—which seeks support from international grants, companies, and private donors, including supportive collectors—operates within a network of for-profit and non-profit institutions, many of which are affected by poor funding and a lack of necessary facilities, topped with self-exploitation at pretty much every level.

“Gaudiopolis” – children’s home led by Gábor Sztehlo, 1946, photo: Mariann Reismann, courtesy of Lutheran Museum, Budapest

But despite the vibrancy of the cultural sector, especially of the young scene, the crises-enhanced “survival mode,” both in the arts and in society, prevents substantial planning.

Other collective initiatives include the Studio of Young Artists’ Association, which, despite its precarious condition, is one of the oldest headquarters for emerging artists, residencies, curatorial projects, and studio facilities. Within its premises and through a joint initiative with the Hungarian University of Fine Arts and C3, they also run LABOR, a small gallery space for young artists and curators to experiment, host talks, and mount monographic and group exhibitions.[49] The non-profit Omnivore Gallery was launched by curatorial graduates with international experience in 2015, and there are also more commercially driven young enterprises such as Chimera Projects and Trapéz (which runs a successful program of local and international emerging artists) alongside the more established for-profits, including Inda Gallery, Viltin Gallery, Molnár Ani Gallery, Erika Deák Gallery, art+text, and the residency and project space Budapest Art Factory.[50] Among the specialized spaces are Gallery8 – the Roma Contemporary Art Space, launched by the European Roma Cultural Foundation in August 2010, and FERi, a feminist project space opened by former Ludwig Museum curator Kata Oltai in October 2016.[51]

Coming out of the rather resourceful younger generation of artists and curators, the five-member curatorial collective Teleport,[52] active since 2015, has used the current institutional vacuum as their point of departure, creating a migrating gallery space that also appropriates various non-art venues and social media, where they run the series Afterwork, a regular informal conversation with artists, with edited summaries published online. Their mobile video gallery Cinema Teleport debuted at Bánkitó,[53] a socially engaged, multi-genre festival, whose civil-cult programs address topical issues such as, in 2016, the refugee crisis and, this summer, the hazards of corruption.

But despite the vibrancy of the cultural sector, especially of the young scene, the crises-enhanced “survival mode,” both in the arts and in society, prevents substantial planning. As curator, OFF-Biennale team member, and former Mezosfera co-editor Nikolett Erőss recently noted, “For me it’s devastating to see that the younger generations have no memory of the ‘normal’ institutional operation. For them, this austere and precarious condition has become the paradigm. Few complain, but there is not much capacity and intent to think long-term and within historical contexts.”[54] The challenge is, however, much more complex and pressing than just securing space and the sustainable and publicly visible operation of critical contemporary culture. What is crucial and inevitable for this sector is to take the lead in rethinking its public institutional responsibility and how it should fulfill its sociocritical functions while proposing a new cultural political vision and drafting policies that include sustainable operation, the reclaiming of its institutions, and the right to autonomous, state-guaranteed operation. The redefinition of publicness is an active task that needs to be part of the organized political resistance. I have to agree with Árpád Schilling: it’s no longer a question of choice.

This text was written in February 2017 and revised in July while I was transitioning between jobs in Sweden and Ireland. I don’t propose this to be an exhaustive survey, but more a brief and necessarily partial report on the climate under which the critically aware art scene in Budapest operates.

I would like to thank to Ágnes Berecz, Nikolett Erőss, Zsófia Frazon, and Natasha Schastneva for their support and insightful comments, and my copy editor Jaclyn Arndt for her dedicated work.

All links were accessed July 2–7, 2017.

[1] Árpád Schilling, “Azt kéne mondanom: végem van” [I should say this is the end of me], interview by Andrea Tompa, Magyar Narancs, August 2015, http://magyarnarancs.hu/szinhaz2/azt-kene-mondanom-vegem-van-93815/?orderdir=novekvo [in Hungarian].

[2] See http://trafo.hu/en-US/luzer-nov. On the Krétakör Workshop Foundation and its projects, see http://kretakor.eu/hu/home/.

[3] The European Cultural Foundation Princess Margriet Award 2016 acknowledged Krétakör’s cultural and educational commitment, especially their Free School, launched in 2013. See http://kretakor.eu/uncategorized/freeschool-the-first-3-years/.

[4] Krétakör Workshop Foundation, which closed due to funding issues in 2016, is considered a model within the non-profit sector. The journalist Anna Frenyó writes: “One needs to be highly determined about one’s artistic ideas and participate in international networks and co-operations to find funding for quality art. Krétakör and Workshop Foundation are such models, for example, which have managed to create something out of nothing. The problem is that these small initiatives coming from the non-profit sector are not encouraged by our current cultural funding system to step up to higher levels—to municipal and state funding. As a result, critical, independent voices are seriously discouraged in the end.” Anna Frenyó, “Theatre Financing and the Independent Theatre Scene,” Heinrich Böll Foundation, December 24, 2014, https://www.boell.de/en/2014/12/29/theatre-financing-and-independent-theatre-scene.

[5] View Schilling’s video at http://hvg.hu/kultura/20170405_schilling_arpad_nemzeti_konzultacio_video [in Hungarian]. For more on the consultation questionnaire, see Eva S. Balogh, “National Consultation, 2017: “Let’s Stop Brussels!,” Hungarian Spectrum, April 2, 2017, http://hungarianspectrum.org/2017/04/02/national-consultation-2017-lets-stop-brussels/.

[6] Among the authors of surveys on the Hungarian political-cultural situation are art historian Edit András, former Ludwig Museum director Barnabás Bencsik, Polish curator and critic Stach Sablowski and the participants of the two-day symposium Perfect Harmony in Athens on November 27–28, 2015, which shared artistic, activist, and political dilemmas of Central Europe. The conference House of Cards and What to Do about It: Institutions Today was hosted by WHW in Zagreb in July 2016, to which I contributed a presentation. More recent articles come from curator Eszter Szakács and artist and sociologist Ágnes Básthy.

On the Athens conference, see:

Tereza Papamichali, “Perfect Harmony. Recent Art and Politics in Eastern Europe,” SZUM, January 1, 2016, http://magazynszum.pl/krytyka/transitions-3-symposium-perfect-harmony-recent-art-and-politics-in-eastern-europe/.

Edit András, “Hungary in Focus: Conservative Politics and Its Impact on the Arts. A Forum,” ARTMargins, September 17, 2013, http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/interviews-sp-837925570/721-hungary-in-focus-forum.

Barnabás Bencsik, “The Captured Institutions of an Art Scene: Hegemonic Tendencies in Hungarian Cultural Politics since 2010,” in Art and the F Word: Reflections on the Browning of Europe, ed. Maria Lind and What, How & for Whom/WHW (Berlin: Sternberg; Spånga: Tensta konstall; Zagreb: What, How & for Whom/WHW, 2014).

Stach Sablowski, “Po prostu nas wyśmiali” [They just laughed at us], Dwutygodnik.com, May 2015, http://www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/6548-po-prostu-nas-wysmiali.html [in Polish].

On the Zagreb conference, see:

“Symposium: House of Cards and What to Do About It: Art Institutions Today,” This Is Tomorrow, http://www.thisistomorrow.org/activities/house-of-cards-and-what-to-do-about-it-art-institutions-today/.

Eszter Szakács, “The Unofficial Art and Positive Forms of Resistance Today in Hungary,” Independent Curators International, October 13, 2016, http://curatorsintl.org/research/unofficial-art-and-positive-forms-of-resistance-today-in-hungary.

Ágnes Básthy, “What Can Be Said about the State of Hungarian Art?,” Political Critique, March 15, 2017, http://politicalcritique.org/cee/hungary/2017/hungary-art-protest-culture/.

Another useful reference on the institutional and artistic scenes is Zoltán Kékesi, ”A Short Guide to Hungary’s Contemporary Art Scene,” ARTMargins, October 24, 2010, http://www.artmargins.com/index.php/2-articles/605-short-guide-hungary-contemporary-art-scene-article

[7] For more, see Lívia Páldi, “Back to the Future: Report from Hungary,” e-flux journal, no. 23 (March 2011), http://www.e-flux.com/journal/23/67801/back-to-the-future-report-from-hungary/.