Safari w kurniku. Scena galeryjna w Bukareszcie / Safari in a henhouse. The gallery scene of Bucharest.

For English version scroll down

PL

Miasto i scena galeryjna pasują do siebie w Bukareszcie jak ulał. Wszystko się tu nawarstwia, tworzy niespodziewane zbitki i wiecznie pozostaje w stanie lekkiego chaosu – od nawiązującej do Haussmannowskiego Paryża Calea Victoriei po kruszącą się betonową pustynię wokół pałacu Ceaușescu. To rozchybotanie to efekt nie tylko nawiedzających miasto regularnie trzęsień ziemi, ale i ułańskiej fantazji jego budowniczych. Ta bowiem nie była jedynie domeną rządzącego przez ponad dwie dekady dyktatora. Na przykład, już w latach dwutysięcznych postanowiono obok dziewiętnastowiecznej katedry św. Józefa wybudować okazały biurowiec, nazwany Cathedral Plaza. Pół biedy, że architektonicznie pasuje on do krajobrazu jak pięść do nosa – okazało się, że podczas budowy naruszono strukturę świątyni. Mimo sądowego nakazu wyburzenia stoi więc toto dokończone, ale puste, w tej dziwacznej symbiozie między starym i nowym, w mieście, gdzie nic nie jest niemożliwe. Nie inaczej wygląda bukaresztański pejzaż galeryjny, równie fragmentaryczny, nieco prowincjonalny, ale i z wieloma pomysłami na siebie.

Centrum na peryferiach

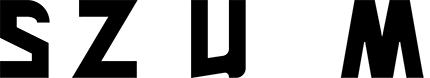

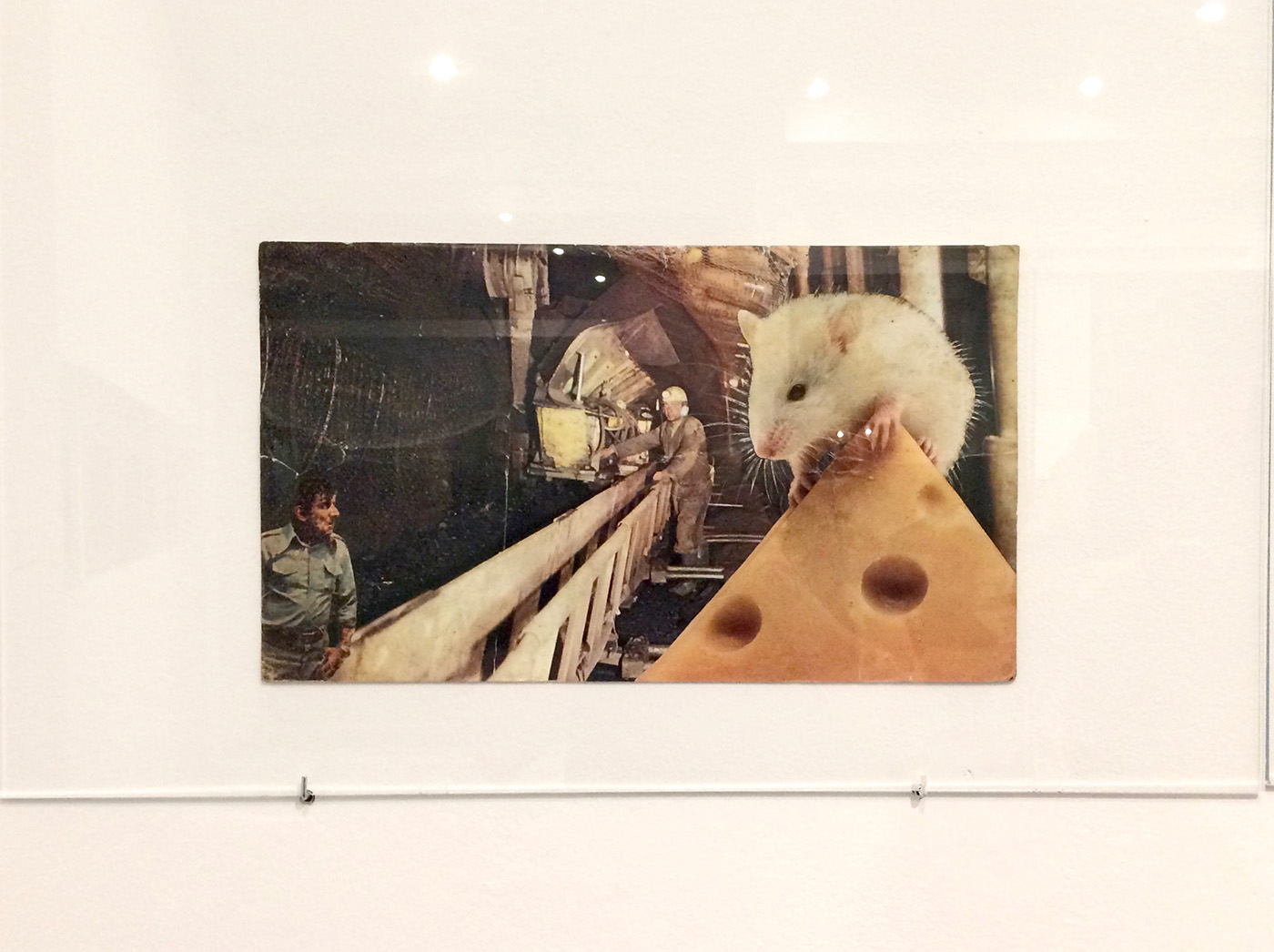

Pierwszą prywatną galerią z prawdziwego zdarzenia w Bukareszcie był założony pod koniec 2002 roku H’art. Choć nie jest dziś naważniejszym punktem na mapie miasta, nie tylko istnieje, ale i nieco się rozrósł – do pierwotnej galerii dołączył w innej lokalizacji H’art Appendix. Jak przystało na galerię definiującą lokalną scenę, H’art ma profil generacyjny – większość artystów, których reprezentuje to pokolenie, które dojrzewało już po zmianie ustrojowej. Galerzysta Dan Popescu zebrał pod szyldem nowej galerii najciekawszych przedstawicieli ówczesnej młodej sztuki rumuńskiej. Jak na ironię, największy gwiazdor galerii to żaden młody wilczek, ale urodzony w 1946 roku artysta samouk, o aparycji i stylówce przeczołganego przez życie kowboja. Nie bez powodu – historia Iona Bârlădeanu to bodaj najbardziej spektakularna w rumuńskim świecie sztuki inkarnacja toposu „od pucybuta do milionera”. Zanim trafił na niego łowiący talenty galerzysta Bârlădeanu był bowiem bezdomnym, który dla rozrywki wyklejał pieczołowicie kolaże ze znalezionych na ulicach kolorowych magazynów. Kiedy już H’art go do siebie przytulił, stał się w oka mgnieniu celebrytą. Wprawiono mu brakujące zęby, kupiono mieszkanie, do czego nieprzyzwyczajony do spokojnego mieszczańskiego życia artysta długo zresztą nie mógł przywyknąć. Nie tylko ze względu na atrakcyjną z PR-owego punktu widzenia biografię stał się on główną gwiazdą galerii. To właśnie w sztuce Bârlădeanu odbija się właściwie najpełniej najnowsza historia Rumunii. Cały transformacyjny bigos, z wizerunkami Ceaușescu i pomnikami Lenina, sielskimi krajobrazami wsi, kaskadami fruwających w powietrzu banknotów, ociekającymi złotem świątyniami, wycinkami z zachodnich reklam i pisemek pornograficznych…

Ion Bârlădeanu, Profana Comedie, H’art Appendix, widok wystawy

H’art to jedna z galerii bezpiecznie ulokowanych w reprezentacyjnym centrum miasta, choć najpełniej charakter lokalnej sceny oddaje nie centrum, gdzie jak w większości innych miast skupiają się w końcu najważniejsi gracze, ale postindustrialny kompleks Combinatul Fondului Plastic na północnym krańcu miasta, w rejonie, gdzie nie dochodzi już metro. Parę kroków od jednego z bulwarów zaczynają się dzikie łąki, za ciągnącymi się po horyzont połaciami krzaków majaczy iglica Pałacu Wolnej Prasy – mniejszego kuzyna stalinowskich wieżowców w rodzaju moskiewskich „siedmiu sióstr” i warszawskiego PKiN-u. Kompleks kombinatu wbrew temu, co mogłaby sugerować jego lokalizacja, nie jest jedynie domem dla super-offowych inicjatyw galeryjnych. Przeciwnie – to tu, w okazałej hali mieści się aktualna siedziba galerii Nicodim, obok Planu B z Klużu najbardziej znanej i po prostu najbogatszej galerii komercyjnej. Z tym, że w przypadku Nicodima kolejność była odwrotna – swoją pozycję galeria zbudowała jeszcze za oceanem, w Los Angeles, przypieczętowując ją tylko otwarciem filii w Bukareszcie.

Format galerii Sandwich wymusza działania site-specific, które jak dotąd, w niedługiej historii galerii, cechowały się urzekająco eskapistycznym humorem.

Na tle Nicodima, reprezentującego rumuńską czołówkę średniego i młodego pokolenia, od Cipriana Muresana po Razvana Boara, ujawnia się cała egzotyka Combinatul Fondului Plastic, swego rodzaju miniatury całej lokalnej sceny, na której sąsiadują przez ścianę galerzyści o międzynarodowej pozycji i eksperymentalne atrist-run-spaces, a pomiędzy nimi zalegają złogi akademickiego próchna. W tym przypadku dosłownie – w postaci tworzonych przez jednego z rezydujących tu artystów gargantuicznie rozrośniętych drewnianych rzeźb, lokujących się gdzieś pomiędzy akademickimi koszmarkami a sztuką ludową. Na terenie Combinatul wynajmują bowiem pracownie liczni artyści, choć niekoniecznie przekłada się to na powstanie skonsolidowanego środowiska, bowiem pochodzą z zupełnie różnych bajek. Jedni z bajki potransformacyjnej, zorientowanej we współczesnej sztuce, często uzupełniających edukację artystyczną za granicą, drudzy z alternatywnej rzeczywistości akademicko-związkowej. Choć akurat w Rumunii rzeczywistość ta jest nieco mniej alternatywna i potrafi niespodziewanie przenikać się z resztą świata sztuki.

Tutejszy związek artystów, instytucjonalny odpowiednik rodzimego ZPAP-u, ma wciąż o wiele silniejszą pozycję niż ten ostatni. ZPAP-u w polskim życiu artystycznym praktycznie nie widać, poza tymi galeriami sieci BWA, którym po 1989 roku mniej się poszczęściło, tymczasem w Rumunii na związek artystów można się co rusz natknąć w samym centrum tutejszego artworldu. Uniunea Artiștilor Plastici din România dysponuje licznymi placówkami na terenie całego miasta, w tym całym kompleksem Combinatul, i choć skupia w swoich szeregach artystów raczej trzeciorzędnych, przez swoje rozproszenie pozostaje stosunkowo otwarty – nawet magazyn „ARTA”, najważniejsze rumuńskie pismo artystyczne, wydawany jest ze związkowych środków. Gorzej wygląda kwestia artystycznego szkolnictwa, nie tylko uniwersytetu. Na terenie Combinatul znajduje się liceum plastyczne, dla którego sąsiedztwo z Nicodimem to przecież wymarzona lokalizacja. Jednak kiedy mijamy budynek z przedstawicielami tutejszego środowiska w drodze na wernisaż w galerii Sandwich, dają oni jasno do zrozumienia, że w praktyce to raczej zamknięta twierdza o niskim poziomie nauczania. Najciekawszym miejscem na terenie tej miniatury Bukaresztu, a może i całego miasta, jest za to wspomniany Sandwich.

Prowadzona przez czteroosobowy zespół (Daniela Palimariu, Cristian Răduță, Alexandru Niculescu i Silviu Lixandru), w większości złożony z artystów, którzy sami na terenie kompleksu wynajmują pracownie, to w pewnym sensie parodia galerii. Zamiast przystosowywać na potrzeby wystawiennicze którąś z opustoszałych hal i stawiać w środku białe ściany, jak zrobił to podążający grzecznie ścieżką Profesjonalnej Zachodniej Galerii Nicodim, twórcy Sandwicha woleli urządzić w nich własne pracownie, galerię zaś ulokowali w najbardziej absurdalnym nie-miejscu na tym terenie – w szerokiej na ledwie półtora metra przestrzeni na wolnym powietrzu, pomiędzy dwoma blaszanym budkami. Format galerii wymusza więc działania site-specific, które jak dotąd, w niedługiej historii galerii, cechowały się urzekająco eskapistycznym humorem, który wypada ożywczo zwłaszcza w kontekście porządno-nudnawego Nicodima i wysiłków innych galerzystów w mieście.

Dan Vezentan na swojej wystawie Feed Me / No Gravity zapełnił kanapkową przestrzeń między dwoma blaszakami iluzjonistyczno-futurystycznym kurnikiem, drewniany szkielet odpicowując przy użyciu luster i neonów, optycznie powiększających przestrzeń. Efekt końcowy wygląda jak scenografia Odysei kosmicznej przeniesiona w realia rumuńskiej wsi. Kosmiczny motyw wykorzystał też w swojej wystawie jeden z twórców Sandwicha, Cristian Răduță, który w ramach Emergency Measures zainstalował tam powracający często w jego praktyce motyw – model rakiety kosmicznej, w tym przypadku z przytroczoną do kadłuba palmą. Răduță kpił w ten sposób zarówno z nieudanych planów podboju kosmosu, jak i najbogatszego procenta mieszkańców Ziemi, deklarując, że jeśli trzeba będzie z niej uciekać, on zatroszczy się, by na kolonizowanej planecie nie zabrakło palm. Wbrew pozorom Sandwich nie jest jednak niszowym wybrykiem grupki artystów, wyrzuconym gdzieś na margines rumuńskiego świata sztuki. Takich miejsc też tu nie brakuje – jednym z nich jest Make a Point, galeria, która oprócz kawałka postindustrialnej hali w innej, także dość oddalonej od centrum dzielnicy ma do dyspozycji wieżę wodną, w której czasem organizuje wystawy (nazwaną, a jakże, Art Tower). Wbrew nazwie twórcy Make a Point nie bardzo wiedzą, co ze swoją przestrzenią zrobić, przez co choć można trafić w niej na dobre wystawy głównie młodych artystów, pozostaje ona na uboczu i większości ludzi nieszczególnie chce się do niej jeździć.

rakiety w pracowni Cristiana Răduțy

Czego nie można powiedzieć o Sandwichu – podczas pobytu w Rumunii trafiłem akurat na wernisaż wystawy World Attractions Dana Perjovschiego, czyli rumuńskiego klasyka i gwiazdora na skalę europejską. Perjovschi blaszane ściany galerii potraktował jak drzwi lodówki i obwiesił je pamiątkowymi magnesami z całego świata. Rozpuszczając wici przede wszystkim po zagranicznych instytucjach sztuki, metodą rodem z czasów świetności mail artu, zebrał poszczególne obiekty. W tym przypadku najważniejsze jest jednak nie „co”, a „kto” – w końcu to nazwiskami buduje się kapitał symboliczny, a zapraszając do siebie Perjovschiego (przy okazji przynoszącego naręcza pamiątek z Tate czy MoMA), galerzyści z Sandwicha wskoczyli w sam środek bukaresztańskiego mainstreamu. Artysta zresztą doskonale o tym wie, a World Attractions to właściwie żartobliwy pokaz siły i globalnego usieciowienia małej galerii na dwóch blaszanych ścianach gdzieś na krańcach miasta, która, jak zauważa Perjovschi, może stać się bardziej rozpoznawalna globalnie niż otoczone murem muzeum w centrum miasta, w tym przypadku ukryte w głębi Pałacu parlamentu MNAC.

Pieniądze to nie wszystko

Jeśli serce bukaresztańskiej sceny galeryjnej bije między dziurawą drogą a połaciami nieużytków, to tutejsze targi sztuki, zorganizowane z rozmachem w budynku pośrodku reprezentacyjnej Victoriei są obrazem nędzy i rozpaczy. Bardzo by chciały być pokazem tego, co w stolicy Rumunii najlepsze, ale zamieniają się we własną parodię. Już nazwa brzmi tak absurdalnie, jak sama idea targów sztuki w Bukareszcie – Art Safari. W Bukareszcie istnieją rzecz jasna dobre komercyjne galerie, choć jest to wciąż bardzo małe grono. Żadnej z nich nie uświadczycie na Art Safari. No, za wyjątkiem Mobiusa, programowo skoncentrowanego na sztuce całego regionu Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, którego twórczyni z uporem twierdzi, że lepiej podnosić nieco poziom, niż bojkotować imprezę. Jest też Sandwich, ale po jego ekipie wszystkiego się można spodziewać.

Bukaresztańska scena galeryjna wciąż pozostaje młoda. Bardziej niż w jakimkolwiek kraju w regionie ciąży nad nią polityczne pęknięcie, a galerie, które pamiętałyby czasy komunistyczne, w rodzaju Galerii Foksal, tutaj po prostu nie istnieją.

Poza tym próżno jednak szukać na targach na przykład Ivan Gallery, ulokowanej w rezydencyjnej dzielnicy w cieniu pałacu Ceaușescu, która zgarnia część z czołówki średniego i młodego pokolenia, czy Anci Poterasu, skupiającej się głównie na młodych artystach, lub Eastwards Prospectus, podobnie jak Mobius prezentującej u siebie artystów z regionu, w tym Karolinę Bregułę. By jakoś zapełnić ledwo jedno piętro przeznaczone na galeryjne boksy, Art Safari otwiera się na wszystkich, którzy szarpną się na odpowiedni wydatek. Stać cię na miejsce na targach? Zapraszamy serdecznie. Nie tylko tutaj rządzi ta reguła, ale w przypadku tak małej sceny brak selekcji działa zabójczo. Targi toną więc w zalewie komercyjnych gniotów najgorszego sortu, przede wszystkim koszmarnego pop-surrealizmu rodem z pinteresta. Nic dziwnego, że większość galerzystów ani myśli wygłupiać się w takim towarzystwie. Jest nawet jedna (niekomercyjna, co w tym kontekście tylko zwiększa poziom absurdu) galeria ze Szwecji i odrobina niemieckiego planktonu, i już można pochwalić się międzynarodowym zasięgiem targów.

Jednak nawet organizująca targi fundacja Art Society Cultural Center czuła, że każąc sobie słono płacić za wstęp na taką imprezę nie postąpiłaby zbyt uczciwie (z tego miejsca chciałbym serdecznie podziękować Roxanie z galerii Mobius, dzięki której wraz z Gergelym z węgierskiego artportal.hu uniknęliśmy tego przykrego wydatku). Dlatego na najwyższym piętrze odbywa się jeszcze wystawa, która ma za zadanie symbolicznie legitymizować całe wydarzenie i pokazywać lepszą twarz rumuńskiej sztuki. Udało się wynająć na tę okazję belgijskiego kuratora Wima Waelputa, który przygotował wystawę Notes on a Landscape. Omawianie jej koncepcji nie ma większego sensu, bo jeśli takowa w ogóle istnieje, to jest czysto pretekstowa, a kurator nawet nie starał się zbytnio tego zamaskować. To po prostu the best of rumuńskiej sztuki, od klasyków awangardy i neoawangardy, jak grupa subREAL i Ion Grigorescu po czołówkę młodej generacji, Vlada Nancę i Virginię Lupu. Samym pracom trudno więc coś zarzucić, w większości jest to faktycznie pokaz realizacji bardzo dobrych i pojawiających się z reguły na podobnych wystawach prezentujących przekrój rumuńskiej sztuki za granicą.

Nie do końca za to wiadomo, dla kogo w tym przypadku Notes on a Landscape powstało. Z pewnością nie dla lokalnej publiczności, która to wszystko dobrze zna z innych wystaw, ale też nie bardzo dla kolekcjonerów spoza Rumunii, których targi powinny teoretycznie przyciągać. Wystawa pozbawiona jest bowiem jakiegokolwiek opisu tego, co się na niej znajduje, dostajemy tylko metryczki poszczególnych prac. Gdyby nie to, że wystawa otworzyła się pod koniec mojego pobytu w Rumunii, nijak nie zrozumiałbym kto, z kim, dlaczego i o co tu w ogóle chodzi. Czyżby jednak nikt tak naprawdę nie wierzył, że trafią tu jacyś zagraniczni widzowie, których trzeba byłoby wprowadzić w kontekst? Może to i lepiej – przynajmniej nikt nie dozna wrażenia, że targi są dla tutejszej sceny jakkolwiek reprezentatywne. A tego na szczęście w przeciwieństwie do muzealnych zapychaczy i zachodnich kuratorów kupić się już nie da.

Bukaresztańska scena galeryjna wciąż pozostaje młoda. Bardziej niż w jakimkolwiek kraju w regionie ciąży nad nią polityczne pęknięcie, a galerie, które pamiętałyby czasy komunistyczne, w rodzaju Galerii Foksal, tutaj po prostu nie istnieją. Starsza generacja artystów, dla których szczyt kariery przypadł na czasy świetności reżimu Ceaușescu trafia pod skrzydła kilkorga galerii, ale jako że w Rumunii typ galerii-fundacji, która programowo zajmowałaby się spuścizną konkretnych artystów się nie rozpowszechnił, nie istnieją też galerie skupione wyłącznie na, dajmy na to, neoawangardzie. Na prace chociażby Gety Brătescu można natknąć się w najmniej spodziewanych miejscach. Chociażby między kiczykami w podrzędnej galerii na Art Safari. Niewielkiej grupie galerii udało się skapitalizować nowe fenomeny w rumuńskiej sztuce, zbudować generacyjny profil i ustabilizować się na międzynarodowej scenie na tyle, by przetrwać dzięki samej sprzedaży, ale przez tę profesjonalną fasadę prześwitują ciągle zjawiska charakterystyczne jeszcze dla dzikiego kapitalizmu lat 90. Może więc jednak jest coś na rzeczy z tym „safari” w nazwach targów – jeśli największa galeria wynajmuje od związku plastyków halę pośrodku niczego, a pozostali, nieliczni gracze wciąż jeszcze kładą podwaliny pod lokalny rynek, to skojarzenie z narażoną na odstrzał zwierzyną nie jest takie bezpodstawne.

Art Safari w pigułce – praca Radu Pandele w sekcji The Space

ENG

In Bucharest the gallery scene and the city itself are a perfect match. Everything here piles up, forms surprising blends and remains in a permanent state o slight chaos: from the Calea Victoriei, styled after Haussmann’s designs of Paris, to the cracking concrete desert surrounding Ceaușescu’s palace. Such stylistic swings are down both to earthquakes many of which have hit the city over the years, and to a certain bravado of those who have built this city. This last trait was by no means an exclusive attribute of the dictator who ruled Romania for over two decades. For example, already in the 2000’s next to the 19th century St. Joseph’s cathedral an impressive office building named Cathedral Plaza was erected. The fact that in terms of design it stands poles apart from its surroundings is the least of the worries here. The construction of the tall building turned out to harm the structure of the church. Now, despite a valid demolition warrant, that thing still stands: empty and unfinished, representing a weird symbiosis between the new and the old within a city where nothing is impossible. The same is true of Bucharest’s gallery-related panorama, fragmentary, somewhat provincial, but with many ideas for what it wants to be.

A centre in the peripheries

The first real private gallery to be founded in Bucharest was, in 2002, the H’art. Today, in spite of not being among the top highlights, not only doest it still exist, but it even got extended: the original gallery was joined by a new and separate venue, the H’art Appendix. As is expected of a gallery which defines the local scene, H’art is generation-profiled: most of the artists whose work has been on display here represent the generation which entered adulthood already after the regime change. The owner, Dan Popescu, used his new brand to gather the most interesting artists of the young Rumanian scene of the time. And yet, ironically enough, the gallery’s biggest star is not some young shaver, but a self-taught artist born in 1946 with the looks and style of a veteran cowboy who’s had his share of rough patches in life. But there is good reason for that: the story of Ion Bârlădeanu is arguably the most spectacular incarnation of the from-shoeshine-boy-to-millionaire topos in all of Rumanian art. Before he was discovered by the talent-hunting gallery owner, Bârlădeanu was just a homeless man who, for sheer fun, made meticulous collages from pieces of illustrated magazines he found in the streets. Once H’art adopted him he almost instantly became a celebrity. He got dentures where his teeth were missing, and he was bought a flat. The latter, by the way, took him quite long to get used to, since tranquil bourgeois life was something alien to him. He became the main star of the gallery not just because of the PR value of his biography. It is Bârlădeanu’s art which reflects to the fullest Romania’s recent history: the whole regime-change-caused mess: Ceaușescu’s images and statues of Lenin, idyllic pictures of the countryside, banknotes thrown in the air, temples dripping with gold, slices of ads from the West and cuttings from porn magazines…

Ion Bârlădeanu, Profana Comedie, H’art Appendix, widok wystawy

H’art is one of the galleries safely anchored in the elegant city centre. The character of the local scene, however, is best illustrated not by the centre, where as in most cities most major players are eventually established, but by the post-industrial Combinatul Fondului Plastic located in the far north of the city which cannot be accessed by subway. Just off one of the boulevards there are wild meadows, and somewhere beyond a vast stretch of bushes we can just see the spire of the Casa Presei Libere (House of the free press), a smaller cousin of the Moscow „seven sisters” and the Palace of Science and Culture in Warsaw. The compound of the Combinatul is not, despite its somewhat misleading situation, just a venue of „super off”, alternative exhibitions. On the contrary: its stately main hall houses the current headquarters of the Nicodim which, next to Cluj’s Plan B, is simply the country’s best known and richest commercial gallery. It is worth stressing, however, that Nicodim’s road to success went the other way round: it earned its reputation while still operating overseas, in Los Angeles, and only cemented it by opening its branch in Bucharest.

It is the background provided by the Nicodim, one of Rumania’s highlights when it comes to the mid-generation and the young scene, from Ciprian Muresan to Razvan Boar, against which we start to notice the exoticism of Combinatul Fondului Plastic as a whole. It is a miniature of sort of the entire local scene. Here, in adjacent spaces, we find internationally renowned galleries and experimental artist-run initiatives, somewhere on the way stumbling over some rotting academic old wood. In this case, literally, since one of the resident artists creates gargantuan wooden sculptures aesthetically situated somewhere between academic monstrosity and folk art. All this is because inside the Combinatul various artists rent studios. They do not, however, necessarily form any consolidated circle, which is logical enough, since they come from completely different places and backgrounds. There are those of the post-transformation kind, wide-read in modern art and often also educated abroad, and those representing the alternative reality of academy and associations. Still, it is only fair to point out that in Romania that „alternative reality” is not radically alternative and sometimes displays a surprising capability of interacting with the rest of the art world.

The format of the Sandwich gallery therefore requires site-specific activities. Those, so far, over the span of the gallery’s short history, have been characterised by their charmingly escapist humour.

Romania’s Artists Association, the institutional equivalent of the Polish ZPAP, still enjoys a far stronger position than its counterpart. ZPAP is barely visible in Poland’s artistic life anywhere outside those BWA (Bureau of Artistic Exhibitions) which have had a less fortunate life 1989.

In Romania, meanwhile, one keeps coming across the association at the very heart of the land’s art world. Uniunea Artiștilor Plastici din România has at its disposal numerous venues all across the city, including the entire Combinatul complex. And even though it mostly consists of third-grade artists, it remains quite open thanks to its lack of concentration. Even „ARTA”, Romania’s most important art magazine, is published for the association’s money. The situation looks grimmer when it comes to teaching art, and not just at university level. Inside the Combinatul there is an art high school. One would assume that to be a neighbour of the Nicodim is a dream location. And yet, when on the way to a vernissage at the Sandwich gallery I passed by the school accompanied by members of the local artistic circles, they clearly let me know that what we just saw was in fact a closed bastion with mediocre teaching standards. The Sandwich I just mentioned is, on the other hand, the most interesting spot within this miniature of Bucharest (or maybe even of the whole world).

Run by a four-member team (Daniela Palimariu, Cristian Răduță, Alexandru Niculescu and Silviu Lixandru) mostly comprising of artists who themselves rent studios inside the compound, it is in a way a parody of a gallery. Instead of adapting to its needs one of the emptied production floors and putting in it some white exhibition boards (as Nicodim did in its obsequious western professionalism), the creators of the Sandwich chose to use the space up for their studios. At the same time, they put their gallery in the most absurd non-place of the entire complex: in the open air, in a space not even two yards wide, crammed between two sheet metal pavilions. The format of the gallery therefore requires site-specific activities. Those, so far, over the span of the gallery’s short history, have been characterised by their charmingly escapist humour, which turns out especially refreshing when compared to the dull and ordered Nicodim and the efforts undertaken by other gallery owners across the city.

Dan Vezentan, for his Feed Me / No Gravity exhibition filled the sandwich-like space between the pavilions with an illusionist and futuristic henhouse, smartening up the wooden frame with mirrors and neons which optically magnified the place. The final effect looked as though the set for 2001: a space odyssey had been moved to the world of the Romanian countryside. Another cosmic motif was used by one of the creators of the Sandwich, Cristian Răduță, who in his Emergency Measures came up with an installation resembling one of his often applied motifs, a model of a space rocket. In this particular case: one with a palm tree attached to the fuselage. This way Răduță mocked both some of the failed space conquest ambitions, and the world’s richest one per cent. Once there was a need to flee from earth, he declared, he would see that there would be enough palm trees in the new colony. Despite appearances though, the Sandwich is not a niche whim of a bunch of artists, somewhere in the periphery of the Rumanian art world. Places like that, however, can too be found in the complex. One of them is Make a Point, a gallery which apart from a slice of a post-industrial production floor has at its disposal a water tower in another district, also rather distant from the centre. The place, called rather unsurprisingly „Art Tower”, houses exhibitions from time to time. Unlike the name itself would suggest, though, the people behind Make a Point do not really seem to know how to use their space. They do sometimes come up with good exhibitions, usually ones of young artists’ work, but for most of the time they remain a marginal venue hardly anybody can be bothered to go to.

That last bit is definitely not true of the Sandwich: during my last stay in Romania I happened to attend the vernissage of their World Attractions, an exhibition of Dan Perjovschi, a Romanian classic and an all-European star. Perjovschi approached the sheet metal walls of the gallery as though they were fridge doors and covered them with souvenir magnets from all over the world. He sent out word, mostly to foreign artistic institutions, applying a method peculiar to the heyday of mail art, and this way gathered all the specific objects he needed. In this case, however, the „what” is less important than the „who”. After all, symbolic capital is built with big names, and by inviting Perjovschi (who brought over bucket loads of souvenirs from the Tate or the MoMA) the Sandwich jumped straight into the middle of Bucharest’s mainstream. The artist, by the way, is very aware of all that. His World Attractions is in fact a playful display of power and of the global „networkisation” of this small gallery with two sheet metal walls: a gallery somewhere in the city outskirts which, as Perjovschi himself points out, can soon be globally more recognised than the big museum hidden behind walls in the city centre, in this case the MNAC inside the Palace of Parliament.

Money is not all

Whereas the heart of the Bucharest scene beats between a pot-holed road and a vast stretch of wasteland, the local art fair, held with lots of flair and panache in the elegant Victoriei area, is an abject and sorry sight. This event would very much like to be a display of all the best that Bucharest has to offer, but is instead becoming its own parody. Even its name, Art Safari, sounds just as absurd as the very concept of an art fair in Bucharest. There already are, albeit just a few, good commercial galleries in this city. None of them, however, is to be found at the Art Safari, with the possible exception of the Mobius, on principle focused on the art of the entire region of Central and Eastern Europe. Its creator stubbornly maintains that it is better to slightly contribute to elevating the show’s standard than to boycott the event altogether. There is also the Sandwich, but let us remember that the team behind it is a very unpredictable one.

We will not, for example, find at the fair the Ivan Gallery, situated in a residential area surrounding Ceaușescu’s palace, which aggregates some of the top-notch artists of the young scene and the mid-generation. Nor are present the Anci Poterasu, focusing mainly on the young generation, and the Eastwards Prospectus, which like the Mobius provides space to artists from the entire region, e.g. Karolina Breguła. Just to somehow fill up the single storey dedicated for the gallery boxes, Art Safari opens itself to virtually anyone willing to pay a sufficient fee: „If you can afford the space, you are invited to take part”. It is not the only place where this rule is applied, but in case of such a small scene the lack of selection is genuinely lethal for the standard. As a result, the fair is flooded with commercial rubbish of the worst sort, mostly dreadful pop-surrealist productions one usually sees on pinterest. So, it is hardly surprising that most gallery owners will not ridicule themselves in such company. We will even find here a gallery from Sweden (a non-commercial one, which in this particular context just adds to the absurd) and some German small-fries. That, apparently, is enough to boast about the fair’s „international reach”.

The Bucharest gallery scene is still young. It lives, to a larger extent than any other scene of the region, in the shadow of the political shift. Galleries which remember the communist period are something that simply does not exist here.

As it turns out, even the organisers of the fair, the Art Society Cultural Center foundation, had bad conscience about setting such an elevated admission fee for visitors (here, I would like to wholeheartedly thank Roxana of the Mobius gallery thanks to whom me and Gergely of artportal.hu were spared this painful expense). That is why in the top storey we will find a separate exhibition meant to symbolically legitimise the whole event and show us the brighter aspect of Rumanian art. For this occasion, the officials were able to hire the Belgian curator Wim Waelput who came up with Notes on a Landscape. To dwell on the concept here would not make much sense, because even if it does at all exist, it is merely a pretext, and the curator did not even make much effort to conceal it. The exhibition, really, is a best-of of Rumanian art, from the avant-garde and neoavantgarde classics, such as the subREAL collective and Ion Grigorescu, all the way to the leading lights of the young generation, Vlad Nanca and Virginia Lupu. It is therefore hard to be critical of the works presented here. Those are mostly good and very good, and often appear within similar displays designed as panoramas of Rumanian art for foreign public.

In this particular case, it is hard to see for whom Notes on a Landscape was actually made. Not for the local public, that is for sure, since it already knows all the exhibits. But it does not seem to be much aimed at foreign collectors either, people who theoretically should be attracted by the fair. The exhibition lacks any kind of description of what it comprises. We only get individual imprints for particular works. If not for the fact that the exhibition opened near the end of my stay in Romania, I would not have understood at all who and why did it. And for what purpose. Who knows: perhaps people here genuinely did not expect any foreign visitors who would need to learn the context? Maybe it is better this way, at least no one will leave with the impression that the fair is in any way representative of the local scene. Luckily, being representative is something which, unlike surplus exhibits and western curators, cannot be bought.

Notes on a Landscape, widok wystawy

The Bucharest gallery scene is still young. It lives, to a larger extent than any other scene of the region, in the shadow of the political shift. Galleries which remember the communist period, like, e.g. the Warsaw Foksal Gallery, are something that simply does not exist here. The artists of the older generation who were in their prime in the times of Ceaușescu’s regime were taken in by several galleries, but since in Romania foundation galleries focused on legacies of particular artists have never become popular, there neither are ones dedicated to e.g. the neoavantgarde. And so, for example, Geta Brătescu’s works can be found in the least expected places, for instance: exhibited amongst clichéd rubbish in a second-rate gallery at the Art Safari. A small number of galleries managed to capitalise on the new phenomena in Romanian art, come up with a generation profile and become stable enough internationally so as to get by thanks to sales only. Still, through this professional facade one can see some frictions peculiar to the wild capitalism of the 1990’s.

So perhaps the „safari” bit in the name of the fair is accurate after all. Since the greatest gallery rents from the artists’ association a hall in the middle of nowhere, and the other, few, players are still laying the foundations of the local market, the comparison to game animals at risk of being shot dead starts to seem somewhat justified.

Piotr Policht – historyk i krytyk sztuki, kurator. Związany z portalem Culture.pl, Muzeum Literatury im. Adama Mickiewicza w Warszawie i „Szumem”. Fanatyk twórczości Eleny Ferrante, Boba Dylana i Klocucha.

Więcej