CROSSED LINE. „Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960-1980” in MoMA

A plexiglass box, a life-size model of an office room – two desks, one stool, a telex, a recorder, a microphone, an answering machine. The furniture and equipment by Olivetti. On its front wall two sets of headphones – not so many visitors reach for them automatically. In the headphones one can listen to something like a report or an information service about the war that is referenced in the work’s title. In Italian, English and Spanish, we can read a description of David Lamelas’ Office of Information about the Vietnam War: The Visual Image, Text and Audio (1968). For its scale and meaning this could be the dominant work of Transmissions. Actually, one could say that this kind of “headquarters” could be the exhibition’s center. In spite of the fact that the exhibition questions the very idea of a center. Or, at least, shows a kind of ambiguity towards it, or even wants to see a countless number of centers.

At least this is the conclusion one could get reading a curatorial text that also finds its elaboration in a conversation with Christian Rattemeyer, one of three (along with Stuart Comer and Roxana Marcocci) curators of this exhibition, which is, at the same time, a presentation of MoMA’s collection. As one can read in the press release, “the exhibition features nearly 300 works, including critical bodies of work and installations from the Museum’s collection, half of which are on view for the first time”. It also “explores the radical experimentation, expansion, and dissemination of ideas that marked the cultural production of these decades (which flanked the widespread student protests of 1968) and challenged established art-historical narratives in the West.”

Thus the curatorial statement reveals its main thesis; that curatorial studies in search of alternative centers for the avant-garde found them in the parts of the world mentioned in the exhibition subtitle, with an exceptional focus on conceptual art from 1960 to 1980. However, the very form of the title, as well as its main thesis raises some doubts. Is it really possible that the exhibition structure doesn’t hide any center with a capital “C”? That, despite the good intentions and effort to present the disotations, diversity and multiplicity of parallel conceptual narrations that were occurring in different parts of the world, the very title of this exhibition reveals the impossibility of ultimate withdrawal from the logic of binaries? Isn’t an actual center inscribed in the title (and the exhibition) as a point of view? A starting point to the admittedly multithreaded but still linear narration of the exhibition? And last, but not least, why Eastern Europe and Latin America, and what then about the other parts of the world?

When asked about the motivation for this juxtaposition, Rattemeyer gives two answers. One is practical, connected with institutional background, the second is conceptual. The latter is the consequence, the result of the former; the former, despite explaining the curatorial choice, raises some questions. While the curatorial language is extremely transparent, it provides the important information that nothing more than the very structure of the institution, its administrative level, is responsible for the juxtaposition that appears in the title. Additionally, this forms a kind of opposition between the West and other parts of the world. Therefore, upon the transparent clarity of the curatorial statement occurs a scratch, a kind of a crack between the pragmatic need for order, classification, filling in gaps, continuity, logical implication and linearity, and a sincere desire to use the exhibition as a medium to show parallel alternatives to the artworld’s standard geography. A necessity to break from the old hierarchies.

The exhibition begins in the lobby on the sixth floor where, next to the entrance, one can see Eduardo Costa’s work Names of Friends: Poems for the Deaf-Mute (1969). This 8mm film loop presents the artist himself soundlessly spelling the names of his fiftythree friends. The lack of sound, typical for 8mm film, in the work that opens the exhibition acts as a communiqué about the difficulties of communication. As a metaphor for the transmission of ideas, in an exhibition about the spreading of ideas, this can provoke anxiety.

In the first room, on the contrary, one can enjoy the comfort of overwhelming communication transparency, formal and esthetic order. At this stage the transmission occurs without interference. It introduces the theme of the line which seems to encircle whole exhibition. In this room it is drawing a loop, a meander, an ellipsis, a circle and, finally, turns itself into the spacial form of a sphere. One can see the line in Julie Kiefer’s, Victor Vasarely’s, François Morellet’s and Ellsworth Kelly’s canvases, and creeping into the paintings displayed in relation to sculptures, from Julio Le Parc’s kinetic box, through Piero Manzoni’s caoline on canvas, to Jesus de Soto’s wire and oil. Then the line opens up into the cuts on Lucio Fontana’s canvas and transforms through Lygia Clark’s Bichos, Jesús Rafael Soto’s and Sergio Caramego’s sculptures to Mira Schendel’s Little Nothings. Finally it melts into the “white noise” of the François Morellet’s works and Julio de Parc’s glittering box.

For the artworks collected in the first room, the point of reference, on the historical and geographical level, is the exhibition Art Abstrait Constructif International that took place in Denise René gallery, Paris, in 1961. Denise René was a gallery that claimed that for the avant-garde it is necessary to create a space for an exchange of the ideas. Therefore the gallerist organized exhibitions with artists from Eastern Europe (Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński amongst others), as well as those from Latin America. The constructivism mentioned in the exhibition title was the first link for the East-South line. Constructivism, as one of the keystones of the Russian avant-garde before the Second World War, had a very strong impact on the Eastern European artworld. At the same time, it was an important point of reference for Latin American artists – for example Argentinian Lee Parc, or Venezuelan Soto during their residencies in Paris used to refer to constructivism as the base of their research in the field of kinetic art.

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints—Face), 1972, Museum of Modern Art, New York, courtesy Galerie Lelong

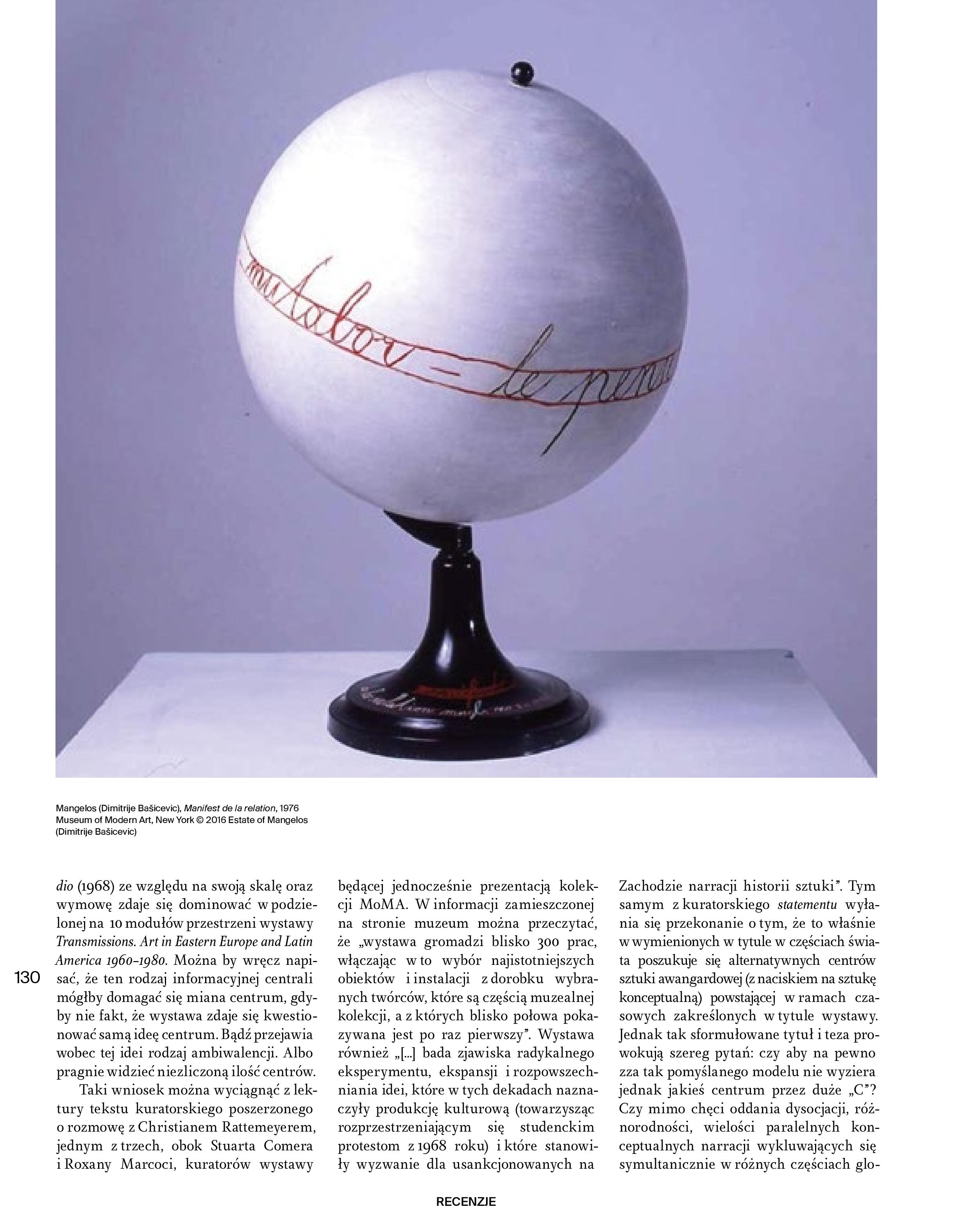

In the context of Latin America, constructivism was used in reference to nature, and often adopted a ludic character, that one can see in the kinetic objects. This joyfulness and desire to experiment is something completely different than one can see in the constructivist tradition in the Eastern Bloc, with its connection to the pre-war soviet avant-garde and its ideas of transnationality with a strong communist background. The Yugoslavian artists (who were not, as the curators correctly stress, limited to socialist-realism), exhibited in the first part of the exhibition, such as Julije Knifer, Dimitrije Bašičević (Mangelos) and Josip Vaništa, didn’t so much question art institutions, as produce more fundamentally nihilistic work. Their manifestations of their lack of political agency, the void standing behind the artistic gesture – this is the background of actions such as Gorgona’s. This phenomenon reveals something very interesting and very characteristic of art from the Eastern Bloc. Namely it shows how a desire to continue the tradition of the pre-war avant-garde relates to a fundamentally utopian belief in the impact of art on a political agenda.

For Gorgona’s and other anti-art groups, such as the Yugoslavian OHO (1966-1971), Aktual from Czechoslovakia (1962-1964), and the Venezuelan group El Techo de la ballena (1961-1968), the main means of artistic expression, besides mail-art as the ultimate device of transgressing the boarders, was editing independent magazines and books. The curators of the exhibition want to see this practice as a manifestation of “skepticism toward authority, including that of art itself, emphasized creative production outside a market context”. While this sentence, presenting capitalism as a form of (oppressive) power, is adequate to the collective from Caracas – inspired by the socialist revolution in Cuba, beat generation’s writings and surrealism – used in the context of the Eastern Europe, it raises some questions. Even regarding Yugoslavia, the country most open to the Western market, the negation of authorities and state in the Eastern artistic environment was more a reaction to mechanisms limiting the freedom of artistic expression than a pure critic of capitalism. This portion of the exhibition, along with several others, reveals some lack in the curatorial concept in building analogies between Eastern Europe and Latin America.

The line, as a the dominant visual trope of the exhibition, organizing it in a structural, formal and symbolic way, in the first room more vivid and entangled, in the “anti-art” room, it paradoxically behaves more civilly. It runs linearly and accompanies the chronological order in the presentation of performance’s records. Amongst this huge number of files, only a very piercing and patient observer would recognize the line in the forms of robes, ribbons, the curved sticks in the photographs of Milanko Matanovic’s Summer Projects or, in a diffused way, in the works of El techo de la ballena. In one issue of its magazine-manifesto Rayado sobre el techo (1940-1980), one can see a photograph with a series of thin, white stripes or rays covering its surface in a manner that makes it almost impossible to see the image underneath. Thus another meaning of the Transmisions’ line emerges – it is no longer a metaphor of continuation, communication, the spreading of ideas, it is their opposite – the line that deletes or distracts from a message. That communicates, above all else, the lack of any unequivocal communication through images.

Works by Dimitrije Bašičević’s (Mangelos) and Josipa Vaništa’s presented in this part of the exhibition give further meaning to the line within the context of conceptual art’s idea of the dematerialization of the artwork, and increase its significance for Transmissions itself. Vaništa in Übermalung (1959-1965) – a work that is materially based on photography of an exhibition of landscape painting – made the gesture of “overpainting the abstract”. Whereas Mangelos in Manifest de la relation (1976) and Manifest diguraski (1977-78) overpainted globes. The line, as taken from school notebooks, runs along in parallel with text inscribed within. The meaning and form of the text again seems ambiguous. On the one hand, it postulates building transgressive relationships, on the other it highlights the inevitability of the dematerialization of art. Doesn’t the dematerialization as a continuation of the idea of non-objective art – the basis of the soviet constructivism – presented in the context of global networking, the idea circling the world sounds ambivalent? If the pre-war soviet avant-garde, with its dream of an art that, as communism, knows no borders, had been utopian, than the utopia that Gorgona’s artist practiced was converted into nihilism. From this perspective dematerialized art could be transgressive and non-existing at the same time.

The next part of the exhibition introduces more information about the structure of itself. The lines tightly wrapped around the artists from Eastern Europe and Latin America split up and start to loosely intertwine. The artistic positions seems still parallel but it would be pointless to search for close analogies. It calls to mind jazz improvisation, the intersecting of music themes, with their polyphony and relations between main themes and counterpoints. There is still a linear presentation (from 1960-80), but one can find here the sinusoid of the dynamics of political engagement inscribed in the display. From the activist increase to the political withdrawal, from Eastern European artists detachment to the direct political engagement, to the Latin Americans who come on stage wielding the mass media.

The dialogue with the mass media initiated by Instituto Torcuato di Tella from Buenos Aires between 1950-1970, is presented here with the three strong examples. Beside’s David Lamelas’ Office of Information about the Vietnam War mentioned above, there is Marty Minujín’s Simultaneidad en symultaneidad (1966), and Oscar Bona’s 60 metros cuadrados y su information (1967). The first takes the form of records documenting part of the action Three Country Happening that Minujin held together with Allan Kaprow and Wolf Vostel in Buenos Aires, New York and Berlin. This was transmitted simultaneously on television and was one of the first attempts to make use of mass media in the visual arts. The second, found behind Lamelas Office of Information, is one of Oscar Bona’s most famous works and a key example of the marriage of mass media and conceptual art. The “sixty square meters” consist mostly of wire mesh stretched on the floor. While walking on it one can feel quite insecure, being confronted at the same time with a projected 16 mm film of the wire mesh itself. The experience of insecurity is the result of two factors – the physical awareness of mediation by the senses, and the additional mediation by the film. This is the essence of Bona’s and Lamelas’ works in relation to the very character of information. The medium may bring us closer to it, but, at the same time, it holds us back from what is represented. The juxtaposition of these works shows how conceptualism took into account the possibility of the widespread and significant influence of art and, at the same time, put this into question.

The question also appears in Lea Lublin’s work, an artist born in 1929 in Poland, but growing up in Argentina. In her work Interrogations sur l’art, discourse sur l’art (1975), each of a series of questions (“Is art a system of signs?”, “Is art an illusion?”) turns a different color. Lublin’s work, primarily conceptualizing the problem of painting, is followed by Alejandro Puente’s laboratory of colors Todo vale. Colores primarios y segundarios llevados al blanco (1968-70), and Henryk Stażewski’s Color relief, while behind them one can find a strong Polish color accent in the form of Edward Krasiński’s “blue Scotch Tape”. The room presenting Krasiński’s work is a kind of adaption of the Warsaw’s studio he inherited from Stażewski. It additionally displays the artist’s encounters with Daniel Buren and Andre Cadére, and their spontaneous expositions with the dominant theme of horizontal and vertical lines. Here also is Krasiński’s Spear (1963-1964), hanging in the air – a line falling apart into smaller and smaller fragments. This is the way one could for the first one see it presented at the Foksal Gallery Foundation in 2013. For a person from Poland, this very way of presentation works as a mechanical transposition, kind of “copy-paste” operation from a primary context into another.

The context of the Polish artists presented in the exhibition requires a digression to elaborate the problem of the research program preceding the exhibition. As Rattemeyer pointed out, the aim of the five years research dedicated to conceptual art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, besides its meritorious and cognitive aspects, was filling gaps in MoMA’s collection, which means acquisitions. This means that, if we take into consideration for example the Polish art, that all these works presented in Transmissions, besides a Stażewski relief acquired in the 60’s, were bought during the last five years. When asked of the criteria of choice, Rattemeyer replied that for the curators the most important aspect was to consult the representativeness of works with professionals from the local context and to answer to the question: “Does everyone in Poland agree that Stażewski, Krasiński and Ewa Partum are masters? Does everyone in Romania agree that Ion Grigorescu and Greta Bratescu are the most important artists from the 60’s and 70’s, or not – and if not, who is?”. While conceeding the limitations of this consensus, Rattemeyer himself agrees that besides the research itself, the choices also reflect the situation of the global art market.

The choice of Ewa Partum Autobiography, presented here with other feminist artists, could be the outcome of the meaning it has in the exhibition context. Among the names of the famous historical and contemporary male artists that are the “material” of this work – a lettering system building the artist’s name – one can find some that are themselves included in Transmission. In a broader context, the feminist works presented here are focused on reflections on the construction of femininity, at the same time they introduce the theme of an intensification of political and activist tendencies in conceptual art. With regard to the counterculture movements after 1968, Transmissions is heading towards the 70’s. As one can clearly see, women’s art is defined here mostly in terms of self-reflexivity and the analysis of the influence of the media and consumerism on ways of constructing (gender) identities. So we have the Sanja Iveković video with the Coca-Cola bottle in the lead role (Sweet violence, 1974), and her collages with Western women’s magazine covers, In the Apartment/”Elle” March 1975. There is Marina Abramović in Rhythm 5 (1974/94) and, last but not least, a series of the works oscillating around the form of self-portrait: Geta Bratescu’s Towards White (Self-Portrait in Seven Sequences, 1975), VALIE EXPORT’s Action Pants: Genital Panic (1969) and VALIE EXPORT SMART EXPORT” (1970), Ana Mendieta’s Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints – Face) (1972).

It is also worth adding that this group of works by illustrious female feminist artists included (this inclusion is already an almost classical gesture), work by Tomislav Gotovač. With his Circle (1964) film and his most famous sequence of photographs with the half-naked artist Showing “Elle” (1962). As Roxana Marcoci wrote in her essay, Gotovač – the Croatian anarchist and performer in love with the film medium – “opened up a set of critical questions about male-female relationships, the dynamics of desire, the tension between real and imaginary, and the antithesis between images of a distant consumer society and the everyday reality of a socialist world”[1]. And again, one might question the last part of this statement. In actual fact for parts of the Eastern Bloc, especially Yugoslavia, the 70’s was a time of partial opening up to the West, including consumerism. Ipso facto it could meet the critical approach of the local artists. Nevertheless the question remains if this fact authorizes building an analogy between the Eastern Bloc experience and the experience of the actually capitalistic countries of Latin America? And can (Eastern Bloc) feminism, as I have understand from the curator’s statement, be reduced to the problem of the contestation of the capitalistic category of female beauty invented to sell goods?

One might believe that, actually, the beginning of resistance to the mechanisms of the predatory capitalism that fed up on the delicate substance of the social fabric, took place somewhere else. In the countries of South America. These countries – exposed to social inequalities and political destabilization connected with the military dictatorships as well as problems that were a direct result of the foreign policies of the United States, hadn’t consolidated democratic standards. The next part of the exhibition seems to acknowledge some of these facts presenting the works of such an artists as Alvero Barrios, Beatrice Gonzales (Columbia), Leon Ferrari (Argentina), Helio Oiticica i Carlos Zilio (Brasil), the keystones of this display are social and economic inequality, and the central figure of family.

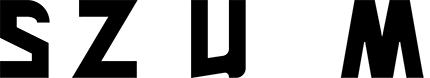

Oscar Bona’s Familia obrera (1968) is part of the artist’s performance records. For this performance Bona, using the exhibition’s production funds, hired a working class family that was supposed to sit on the plinths at the gallery for eight hours a day. Thus the family earned twice the amount that the father would earn in his factory job. Vis a vis the working class family one can also find Fernando Botero’s painting The Presidential Family (1967), presenting the Columbian head of state with his immediate family, the bishop, the general, the dog, plus the “court” painter located on the first plan. The figure of the painter drawn into the canvas brings to mind Velásquez’s Las Meninas (1656), and the famous Goya’s painting in which the artist portrayed the Spanish royal family in all their ugliness (Carlos IV of Spain and His Family, 1800). This juxtaposition of families is supplemented by Marisol’s The Family (1962), followed by the artist’s other well-known sculpture of the same year, Love – a bottle of Coca-Cola vertically stuck into an open mouth – maintained in the Venezuelan pop-art style. At this stage the exhibition is curling to its end. In the feminist room, the line that guided the public through Transmissions turned into the film looped in Gotovač’s projection, then it dematerialized and converted into a sound wave. The jazz so beloved by Gotovač is emanating in the last part of the exhibition. Jazz that nowhere as much as in New York brings to mind a busy street, introduces into the exhibition the theme of activism in the political field, often happening on the streets. This is juxtaposed, in a way, with its reverse – the artists’ actions in reaction to political oppression that take form of ephemeral gestures, and of withdrawal from the public sphere to studio space. In the physical domain, they are separated by a wall that is tightly filled with posters, a mix of works from Eastern Europe and Latin America. Graphic design, as a medium that was less exposed to the operations of censorship, is presented, paradoxically, in the aesthetics of horror vacui.

The reverse of the wall – a room displaying works of, among others, two artistic tandems (Liliana Porter i Luis Camnitzer, Ion Grigorescu i Geta Bratescu) that chose to go back to their studios. Often experimenting with different media – they, the curators claim, present the mature form of conceptualism. These works are defined by their closure to science. They could take the form of a repetition of the circle figure, as in Lilliana Porter’s work (Untitled (Circle Mural), 1973), or Bela Kolařova series of “fake negatives” which relate to the experience of synesthesia (Radiogram Circle, 1962-1963). The theme of searching for the invisible, for mathematical structures hidden behind the perceptible, is further elaborated in Dora Maurer’s works. There is also Bratescu’s The Studio. Invocation of a Drawing (1979), in which artist explores the relations between the studio space and her own body, and Medea’s Hypostasis (1980), in which she used the subtle form of a handmade stitch as an answer to a political horror that almost chokes.

On the other side of the wall the South American activists CADA (Collectivo Acciones de Arte) are represented by deconstructive interventions against the Augusto Pinochet government. In turn in this activist section the Eastern Bloc, not lacking a sense of humor, presents Braco Dimitijević’s Casual Passer-by I Met at 4:30 p.m., Berlin (1976). This photographic documentation records the artist displaying portraits of “common people” in public space in Zagreb, produced in the aesthetics of the large scale banners presenting communist leaders prepared for socialist parades. Besides Dimitijević there is also Jiři Kovanda with documentation of his Contact (1979) action, a walk through Prague and the encounters with random people, and Józef Robkaowski’s From my window (1978-99). In the room the piles of documents are back, with a huge amount of leaflets and names. The direct juxtaposition of artists from Europe and South America is bound by their urge to express themselves in the public space, although the gradations, motivations and even stylistics of their political protest are very different. Reducing this to a lowest common denominator would be a simplification.

The last part of Transmissions is focused on the Video Trans America – an expansive installation by Chilean artist Juan Downey living in New York. On the floor one can see the contours of two Americas. The line guiding the public through the exhibition is back in the shapes of the two continents and then finally takes the form of the concentric circles in an other artist’s work situated in the lobby, beyond the actual space of the exhibition. At specific points of the two America’s map one can see monitors projecting films showing aboriginal habitants of South and Central America – their rituals and everyday life. While traversing the Americas in Downey’s installation, one is participating in encounters with “otherness, which function as a metaphor for understanding his own cultural identity, which is central to the exhibition’s thesis of possible counter-geographies, realignments, alternative models of solidarity, and ways of rethinking the historical narratives of postwar art”.

If the central thesis of Transmissions is the searching for cultural identity then it would be rather the identity of the homo occidentalis, the citizen of the USA and maybe even the inhabitant of New York City (if not the employee of the Museum of Modern Art). Is this true? When asked if Transmissions is an exhibition mainly for the American public, Christian Rattemeyer replied by calling on the statistics of MoMa’s audiences (only 40% of it is from the USA). But the exhibition’s point of departure is stated as clearly as Juan Downey’s (an artist of Chilean roots, but based in New York) work makes us think. Its location makes us to go through South America to reach North America – the USA and New York are the destinations. This is the place where one can make the effort to understand one’s own identity through contact with an other. Downey’s installation works as a figure of the audience’s travel through the exhibition and reflects the travel of MoMa’s curatorial research group. And if the precision, structure and logistics of this research and its outcome in the form of such a dense and multithreaded exhibition is impressive, what pinches is the schema that stands behind it, taken directly from the very internal administrative structure of the institution. A structure that divides the institution into departments (the Latin American Department, Eastern Europe Department, etc.) and that, as the very subtitle of the exhibition reveals, can transmit the message of binary oppositions, the world divided into two, where there is the West and the other parts of the world. This schema, probably highly difficult to omit in the case of a presentation of the museum collection, seems to be contradictory to the central trope organizing the exhibition – the unruly line that symbolizes both the pre-war avant-garde, minimalism, abstract art as a means expression, and the specificity of intricate relations between the artistic environments from distant parts of the world. A line that takes different forms and goes through different fields of art and media. A line that is a connector, a link, a telephone cable, a transmission line, that diffuses itself into a sound wave, dematerializes itself, but is still present. Unfortunately one can hardly be rid of the impression that this line, which wants to be a connection, at the same time works as a dividing line.

[1] Roxana Marcoci, Tomislav Gotovac, “When I open my eyes in the morning, I see a film”, [w:] Post. Notes on Modern and Contemporary Art Around the Globe, http://post.at.moma.org/content_items/547-tomislav-gotovac-when-i-open-my-eyes-in-the-morning-i-see-a-film, date of access: 07.12.2015.

Przypisy

Stopka

- Osoby artystyczne

- Marina Abramović, Artur Barrio, Álvaro Barrios, Oscar Bony, Fernando Botero, Geta Brătescu, Paulo Bruscky, Boris Bućan, Daniel Buren, André Cadere, Sérgio Camargo, Luis Camnitzer, Ulises Carrión, Juan Castillo, Willys de Castro, Roman CieSlewicz, Lygia Clark, Eduardo Costa, Antonio Dias, Braco Dimitrijevic, Juan Downey, Felipe Ehrenberg, VALIE EXPORT, León Ferrari, Lucio Fontana, Gego, Anna Bella Geiger, Beatriz Gonzále, Wiktor Górka, Tomislav Gotovac, Ion Grigorescu, Jiří Hilmar, Miljenko Horvat, Sanja Iveković, Marijan Jevšovar, Ellsworth Kelly, Julije Knifer, Milan Knížák, Bela Kolárová, Andrzej Kostołowski, Jiri Kovanda, Ivan Kožarić, Jarosław Kozłowski, Edward Krasiński, David Lamelas, Julio Le Parc, Jan Lenica, Ken Loach, Lea Lublin, Jan Mach, Vit Mach, Dimitrije Bašicevic, Piero Manzoni, Marisol Escobar, Milenko Matanović, Dóra Maurer, Ana Mendieta, Marta Minujín, Jan Młodożeniec, François Morellet, David Nez, Hélio Oiticica, Ewa Partum, Ivan Picelj, Harold Pinter, Liliana Porter, Alejandro Puente, Antonio Fernandez Reboiro, Józef Robakowski, Miguel Angel Rojas, Alfredo Rostgaard, Dieter Roth, Jan Sawka, Mira SchendelJesús Rafael Soto, Franciszek Starowieyski, Henryk Stażewski, Mladen Stilinović, Sonia Švecová, Endre Tót, Goran Trbuljak, Jan Trtílek, Karel Vaca, Josip Vaništa, Victor Vasarely, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Raoul Walsh, Robert Wittmann, Zdenĕk Ziegler, Carlos Zilio, Raúl Zurita, Brigada Inti Peredo, Brigadas Ramona Parra, CADA, Aktuální Umei, El Techo de la Ballena, Venezuela Gorgona artists group, OHO

- Wystawa

- Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980

- Miejsce

- MoMa - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Czas trwania

- 05.09.2015-03.01.2016

- Osoba kuratorska

- Stuart Comer, Roxana Marcocci, Christian Rattemeyer

- Strona internetowa

- www.moma.org

- Indeks

- Aktuální Umei Alejandro Puente Alfredo Rostgaard Álvaro Barrios Ana Mendieta André Cadere Andrzej Kostołowski Anna Bella Geiger Antonio Dias Antonio Fernandez Reboiro Artur Barrio Beatriz Gonzále Bela Kolárová Boris Bućan Braco Dimitrijević Brigada Inti Peredo Brigadas Ramona Parra CADA Carlos Zilio Christian Rattemeyer Daniel Buren David Lamelas David Nez Dieter Roth Dimitrije Bašicevic Dora Maurer Edgardo Antonio Vigo Eduardo Costa Edward Krasiński El Techo de la Ballena Ellsworth Kelly Endre Tót Ewa Opałka Ewa Partum Felipe Ehrenberg Fernando Botero Franciszek Starowieyski François Morellet Gego Geta Brătescu Goran Trbuljak Harold Pinter Hélio Oiticica Henryk Stażewski Ion Grigorescu Ivan Kožarić Ivan Picelj Jan Lenica Jan Mach Jan Młodożeniec Jan Sawka Jan Trtílek Jarosław Kozłowski Jiří Hilmar Jiří Kovanda Josip Vaništa Józef Robakowski Juan Castillo Juan Downey Julije Knifer Julio Le Parc Karel Vaca Ken Loach Lea Lublin León Ferrari Liliana Porter Lucio Fontana Luis Camnitzer Lygia Clark Marijan Jevšovar Marina Abramović Marisol Escobar Marta Minujín Miguel Angel Rojas Milan Knížák Milenko Matanović Miljenko Horvat Mira SchendelJesús Rafael Soto Mladen Stilinović MoMA OHO Oscar Bony Paulo Bruscky Piero Manzoni Raoul Walsh Raúl Zurita Robert Wittmann Roman Cieslewicz Roxana Marcocci Sanja Iveković Sérgio Camargo Sonia Švecová Stuart Comer Tomislav Gotovac Ulises Carrión Valie Export Venezuela Gorgona artists group Victor Vasarely Vit Mach Wiktor Górka Willys de Castro Zdenĕk Ziegler