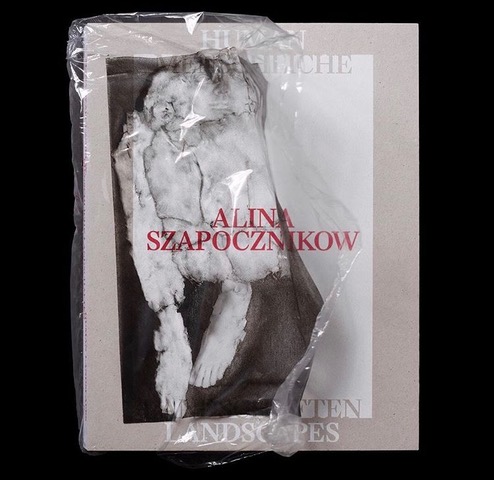

Alina Szapocznikow: Human Landscapes

Alina Szapocznikow: Human Landscapes is the first survey of the artist’s work to take place in Britain at The Hepworth Wakefield, where it was conceived in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, and in Germany, where it toured to the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden,. The exhibition benefits from over a decade of new research and insights gained from the proliferation of long-overdue international museum exhibitions that have established Szapocznikow’s reputation outside of her native Poland. There she enjoyed renown throughout her career and is considered the nation’s most important twentieth-century sculptor. Indeed, large-scale exhibitions such as this would be impossible without the cooperation of Polish museums in which Szapocznikow’s work often sits at the heart of their collections, and around which narratives of twentieth-century Polish art are shaped.

Szapocznikow’s enthusiasm for being photographed with her work also suggests a desire to craft an international profile at a moment when female artists continued in their struggle to gain such recognition.

This exhibitionbrings together over one hundred sculptures, drawings and photographs, spanning Szapocznikow’s career from 1954 to 1973. New presentations of her work offer the opportunity to display unexplored facets of her complex oeuvre, as well as the ways in which it increasingly influences contemporary discourses and artistic practices. At The Hepworth Wakefield, her work is instructively experienced in proximity to works by modern British artists Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and their contemporaries – artists who would have been known to Szapocznikow (Moore, at least, also knew Szapocznikow, chairing a committee which shortlisted her proposal for an Auschwicz-Birkenau memorial in 1957). In particular, a permanent display at The Hepworth Wakefield dedicated to Hepworth’s artistic process – including working models and photography of the artist in her studio – elicits fascinating parallels in sculptural thinking between two artists who shared a desire to express through their work the social and political urgency of the times in which they lived.

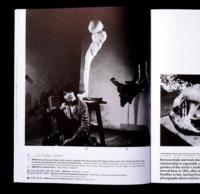

Like Barbara Hepworth, Szapocznikow’s enthusiasm for being photographed with her work also suggests a desire to craft an international profile at a moment when female artists continued in their struggle to gain such recognition. Szapocznikow’s archive contains over seven thousand photographs documenting the artist and her sculpture in the context of the various studios she occupied in Warsaw and Paris. Presented throughout the exhibition, this unusually rich collection of documentary images allows us to examine Szapocznikow’s use of photography both as a means of mediating the effect of her sculpture and as a way to record works that were inherently ephemeral. In these images she appears both fearless and seductive, often bearing a knowing smile that would appear in many of her works in the 1960s. They stand in contrast to the darker experiences Szapocznikow had already confronted in her young life – war, the Holocaust and serious illness – experiences that only present themselves with any transparency in the works she made towards the end of her career. In this contradiction we observe the tension between life and its pleasures, and death and its fears, which becomes the driving force of her work.

Yet as new audiences and contexts are found for Alina Szapocznikow, the need for a continued exploration of her infinitely complex oeuvre remains critical. That her influence on a contemporary generation of artists is so palpable makes this relatively newfound visibility remarkable; it is also testament to the fact that, through a deeply personal lens, Szapocznikow tackled universal concerns that continue to resonate today. In her work, the human body, her life-long subject, emerges as a staging ground for an exploration of human experience in all its physical and psychological reality. Repeatedly, she found profound ways to express the body’s vulnerable place within the matrix of historical, political and societal shifts.

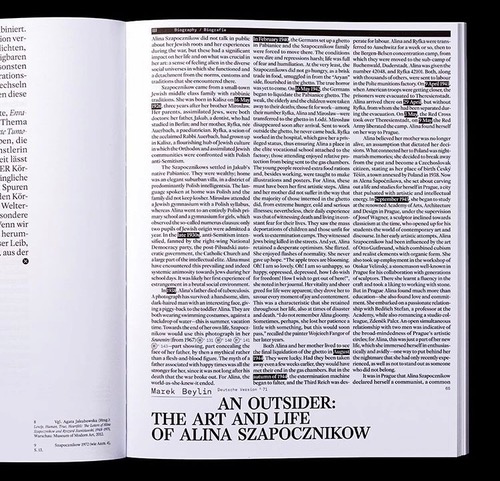

The traumatic events of Szapocznikow’s life have sometimes resulted in overly-biographical interpretations of her work, yet it is impossible to entirely extricate its development from her extraordinary personal narrative. Szapocznikow was born in 1926 in Kalisz, Poland, to a Jewish family of medical professionals. During the early years of the Second World War she lived between the ghettoes in Pabianice and Łódź, before finally being transported to the camps – first Auschwitz then Bergen-Belsen, where she spent approximately ten months working with her mother in the camp hospital. On her liberation she moved to Prague where she enrolled at the Higher School of Arts and Industry to study stonemasonry, later completing her studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Due to illness, she returned to Warsaw in 1951, determined to forge a career as an artist and armed with a formal language shaped by Czech modernism and the artistic developments in post-war Paris. Her immersion in left-wing French humanism and socialist politics (she had also been a member of the Communist Party in Prague) allowed Szapocznikow to accept and operate within the socialist realist style of Poland’s official state doctrine. After a decade in Poland’s shifting political landscape, during which time she evolved many of the fundamental concerns of her work, Szapocznikow returned to Paris in 1963, eager to situate herself at the heart of contemporary artistic developments in Europe. She lived and worked there for the remaining years of her life. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1969 and succumbed to it in 1973 at the age of 46.

Contemporary scholarship has argued compellingly that in her art, Szapocznikow found a means to rebuild or reclaim the body she had witnessed destroyed by the violence and inhumanity of war.[1] Her primary artistic concerns were consistently those of a sculptor, wrestling with materiality, volume, balance, space and light. Nonetheless, the traumatic events that marked every stage in Szapocznikow’s life appear to have driven both her voracious exploration of materials, unorthodox and traditional, and the relentless formal enquiries that questioned the very nature of sculpture itself.

From early on in her career Szapocznikow was attracted to materials that allowed her to create forms with immediacy, acknowledging that they might change with time, or even ultimately deteriorate. Her works are palpably fragile with many now unable to travel for international exhibitions.

A chronologically organised survey such as this exhibition evidences the startling speed with which Szapocznikow moved from one formal idea to the next, typically exploring in only a handful of works something another artist might devote years to investigating. Her earliest mature works included in this exhibition, Pierwsza miłość (First Love,1954) and Trudny wiek (Difficult Age, 1955), are depictions of empowered female figures. They demonstrate her shift away from a strict soviet realist style, but also how her academic training had provided a language of form and technique which she would go on to deconstruct for the rest of her career. Already in these early works it is possible to intuit a sense of willful awkwardness that pushed against classical idealism; only a little later their fleshy contours all but dissolved to reveal the skeletal armature of Ekshumowany (Exhumed, 1955), which confronts us with a body that is broken and crouched low on the ground, anticipating the increasingly floor-based horizontality that would characterise much of her later work.

From early on in her career Szapocznikow was attracted to materials that allowed her to create forms with immediacy, acknowledging that they might change with time, or even ultimately deteriorate. Her works are palpably fragile with many now unable to travel for international exhibitions. Szapocznikow’s sculptures from the late 1950s, such as Maria Magdalena (Mary Magdalene, 1957-8) and Pnaca (The Climbing, 1959), appear to be working to undermine themselves – disproportionate and unable to support their own weight, top heavy and barely able to maintain their balance; others extremely heavy yet made to appear to defy gravity. In these formal decisions we can identify Szapocznikow’s attraction to contradiction and instability – as if depriving her works of the stable ground upon which classical sculptures typically stand.

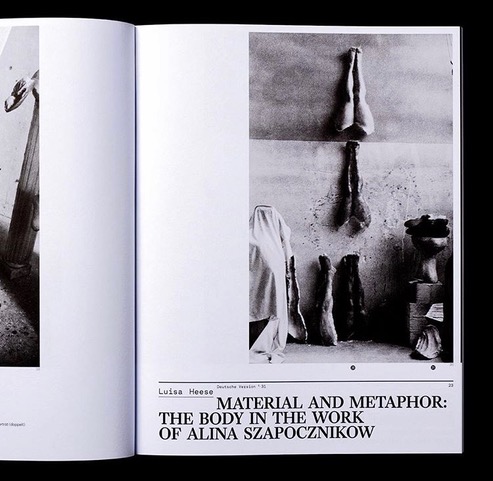

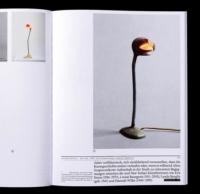

From the early 1960s onwards, Szapocznikow’s work becomes charged with a relentless oscillation between figuration and abstraction, taking her interest in instability in a new direction. Her sculpture becomes so fractured, so metaphorically porous, as to allow found objects to breach their surfaces – a fundamental development that occurred in 1963 when Szapocznikow began incorporating reclaimed machine parts and weaponry into her plaster and cement forms. It is with these works – Machine en Chair (Fleshy Machine, 1963-4), Człowiek z intrumentem (Man with Instrument, 1965) and Goldfinger (1965) – and her earlier Noga (Leg,1962) in which she cast the lower part of her own leg, that Szapocznikow’s achieves an urgent temporality that ties the works to the immediacy of the moment in which they were made. They also for the first time invoke the spectre of the readymade, which Szapocznikow gives a personalised, autobiographical twist, resulting in a prolific series of unsettlingly uncanny and darkly comical utilitarian objects: brightly coloured lamps made from accumulated casts of lips and breasts; her provocative Dessertscomposed of body parts arranged in found pieces of domestic tableware; and her multiple casts of voluptuous bellies, legs and faces which she submerged in thick, oozing pours of black polyurethane foam. These ambiguous and disturbingly sensual works are, on the one hand, a tongue-in-cheek reflection on the mass culture of her times, aligning with contemporary discourses around commodity fetishism being explored by pop artists and those associated with nouveau réalisme, coloured by her experience of Soviet communism and Western capitalism alike. On the other hand, they are also a rebellious battle cry by an artist increasingly frustrated by the impossibility for a female artist to find her place in the male-dominated Paris art scene. These works can be read as symbolic attempts to sell her own body, its parts turned into pleasing, alluring and easy to handle objects that are also repellent in their disembodiment. They bear witness to the complexity of the human body – its pains and pleasures – and to the impossibility of considering it as an undisrupted entity.

Szapocznikow’s use of new materials such as polyurethane and polyester resin mark out this period of her work as her most materially experimental – highlighting how she used certain materials not only for their possibility to create new forms, but also for the ways in which they might embody symbolic resonances. Her attraction to the new polymers being developed in the 1960s, which she researched in several laboratories around Paris, was in part due to their ability to transgress states, from liquid to solid, materialising her own increasing awareness of the passing of time and a desire to capture, and if only temporarily to still its ceaseless progression. This becomes most evident in the works made in the very last years of her life under the shadow of her cancer diagnosis. In her Tumeur (Tumour, 1969) and Fétiches (Fetishes, 1970-1) series personal photographs – and for the first time, occasional direct references to the horrors of the Holocaust – are preserved in translucent polyester resin and coerced into forms resembling tumourous growths. The marked disintegration and discolouration of many of these works due to the inherent instability of the materials, often rendering their encased contents increasingly difficult to decipher, instills them with an added sense of mortality.

Among the last drawings made by Szapocznikow are the Human Landscapes. These dreamlike watercolours are filled with bodies that are falling or hovering, collapsing and disintegrating. Eyes, lips, phalluses and limbs are piled up into earthy masses.

This sense of mortality pervades several large scale installations Szapocznikow produced in the 1970s, including Souvenir from the Wedding Table of a Happy Woman at the Aurora Gallery in Geneva in 1971. On a gauze-covered table in a corner of the gallery she arranged a dense cluster of her Desserts, Tumours and Fetishes. Its title evokes a table that has been left after a wedding feast, the objects the discarded remains of a celebratory ritual gathering. The work, however, is haunted by absence, her sculptures cast as remnants of bodies lost. Sculpture becomes a surface onto which memories are inscribed.

Although Szapocznikow considered herself primarily a sculptor, the selection of drawings and monotypes presented in Alina Szapocznikow: Human Landscapes makes evident the importance of her compulsive graphic practice to both elucidating and complicating her sculpture. Her drawings are most often sketches and studies of forms, but their provisional, repetitive nature – the same motif explored several times on a page – offers insight into an artistic mind constantly explorations sculptural questions, even when working in two-dimensions. Among the last drawings made by Szapocznikow are the Human Landscapes. These dreamlike watercolours are filled with bodies that are falling or hovering, collapsing and disintegrating. Eyes, lips, phalluses and limbs are piled up into earthy masses. Echoing the horizontality of her last works such as Tumeurs personnifiées (Tumours Personified, 1971) and the skin-like surfaces of her Herbier(Herbarium)works, the Human Landscapesare a retrospective glance at a life of fragmented memories held within the body with all its human vulnerabilities.

Szapocznikow’s work is defined by its resistance to monumentality, its propulsive development, its emotive need to reach out to the unknown, and a continuous inclination towards risk. Seemingly allergic to the idea of familiarity, Szapocznikow consistently challenged herself by striving towards the new – be it themes or ideas, techniques or materials – and it is precisely this curiosity that imbues Szapocznikow’s work with its originality and contemporaneity. In 1972, towards the end of her life, she confessed: ‘As for me, I produce awkward objects’, identifying in her sculptures a cultivated indeterminacy born out of inherent antagonisms: between openness and specificity, revelation and threat, weakness and strength, faith and doubt, pain and pleasure.[2] Szapocznikow was determined for each work to exist as a moment of departure rather than as a point of arrival.

While organised chronologically, Alina Szapocznikow: Human Landscapes demonstrates the impossibility of following a singular, coherent path through Szapocznikow’s work. On the contrary, we are presented with a rhizomatic narrative of breaches, failures and detours as a result of the artist’s insistence on always searching out the new. In 1966, at a symposium in Carrara, she wrote: ‘Today’s world, with its political violence, competitive production, sudden, out-of-breath events, cannot find its reflection in the nobility of marble. Fine materials and colour, only in art is there a repose and longing. Creative individuals cannot live on that alone. To express the ‘TODAY’ – how? Where? In what form? In what material?’[3]A parade of searching questions that charges through Alina Szapocznikow’s protean oeuvre, which continues to challenge and provoke today.

The text is was originally published in the book Alina Szapocznikow: Human Landscapes (courtesy of Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw).

[1] Griselda Pollock, 'Too Early and Too Late: Melting Solids and Traumatic Encryption in the Sculptural Dissolutions of Alina Szapocznikow,’ in Agata Jakubowska, ed., Alina Szapocznikow: Awkward Objects (Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art, 2011).

[2] Alina Szapocznikow, statement, March 1972, 'Mon oeuvre puise ses racines…,’ signed typescript. Full reference?

[3] Współczesność, no. 11/1966.