Slovenia’s Populist Wave and the EU’s Latest Culture War

Ljubljana, Slovenia — A digital clock above the Fotopub project space ticks down to 9:00 PM. Somewhere in Ljubljana, a siren blares in the night. Since October 2020, Slovenia’s roughly two million inhabitants have been under a strict curfew. From 9:00 PM and 6:00 AM everyday, as per government decree, a ban on public gathering and the prohibition of large groups is enforced, a move the government says is designed to curb the spread of the coronavirus, but which critics say is also being wielded to silence public dissent after weekly protests nearly led to the collapse of the government last summer.

Since assuming office in March 2020, the Slovenian Prime Minister, Janez Janša, has been accused of eroding media freedoms and of usurping power and corruption. He is often compared to fellow Central European strong armed leaders like Viktor Orban and Jarosław Kaczyński, the veritable architects of the EU’s populist front.

Janša’s government has been at the forefront of raging culture war in Slovenia, targeting everyone from Jasa Mrevlje Pollak, the Slovenian artist who represented the country at the 2015 Venice Biennale; to threatening the status of almost 20 cultural NGOs housed in the government subsidized space Metelkova; to repeated attacks on freedom of the press; through to the targeting the of heads of large cultural institutions based on ideological differences.

That said, Slovenia has a vibrant and critical cultural sector. The Ulay Foundation, dedicated to the life and memory of the German artist born Frank Uwe Laysiepen, whose participatory public performances with Marina Abramovic netted him considerable notoriety in the 1970s and 80s, moved to Ljlubljana to pursue his solo artistic career and found a home in the city before he died. The city was also home to Igor Zabel, the Slovene art historian, curator, writer and essayist who died in 2005. It also boasts MGLC Švicarija, a creative and residency centre in Ljubljana, who in collaboration with the Igor Zabel Association for Culture and Theory annually hosts art critics and cultural residents as part of a well-funded residency programme. Ljubljana also lays claim to one of the oldest graphic arts biennales in the world, founded in 1955, the Graphic Arts Biennale. Late last year, Moderna Galerija, the city’s preeminent modern art institution, hosted a major retrospective of Andrzej Wróblewski. On a smaller level, the itinerant project space Fotopub works with mostly young and emerging artists. All of them cumulatively blend together in a way that makes Ljubljana an interesting cultural nexus.

According to Violeta Tomić, the acting head of the Parliamentary Committee on Culture, the cultural situation in Slovenia today resembles a battleground.

What’s more, voices of cultural resistance have always persisted in Slovenia, despite the latest government’s attempts to curtail it. The Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) group, known for their provocations into the art and public consciousness of life in (post-)Yugoslavia, have long since been using artistic interventions in order to disrupt social and political conventions. Since the 1980s, the group has spawned into a litany of directions, including the famous musical arm Laibach and collective IRWIN. Since 1991, NSK has been operating as a virtual non-territorial state, complete with NSK passport stamps and exhibitions that deconstruct the infrastructure and ideology of statehood. NSK’s name, ironically in German despite being a Slovenian group, mirrors the complicated relationship Slovenes have had with Germans and Austrians over the years, but also the extent to which nationhood composes itself as a cultural and political export.

In Metelkova, a former squat in central Ljubljana that for the past thirty years has been a bustling cultural nexus that houses about a dozen non-governmental organizations, the government’s attempts to wrest control over culture is being done in pursuit of ideological agenda. Nevertheless the group inside remains committed to pursuing free and open cultural expression, including the Peace Center and a Feminist organization, despite the government’s repeated attempts to evict them, they persist and remain.

According to Violeta Tomić, the acting head of the Parliamentary Committee on Culture, the cultural situation in Slovenia today resembles a battleground. The ruling SDS (Slovenian Democratic Party), who have been in power since March 2020, have been engaging in policies Tomic calls “fascist.” “What is happening in Slovenia is fascistic,” Tomić said, noting that her caseload for cultural issues in parliament has become incredibly burdensome since the new government took office. “Everyday there is a new issue […] Today it could be the government’s ugly decision to take away the artistic status from the rap musician Zlatko, tomorrow it could be canceling of the STA [the Slovenian Public Broadcaster], the next day it could the cancelling of financing for films in production, or the terrible conditions for self employed artists.” The situation, according to Tomić, is bleak.

In response to these and other issues, over 1,000 artists and academics in Slovenia recently signed an open letter last November denouncing what they said were numerous incursions by the government to curtail artistic freedoms. According to the open-letter: “The field of culture has been severely affected by the coronavirus epidemic, and it has been further affected by decisions at the Ministry of Culture that threaten living culture, cultural heritage, professionalism and autonomy of decision-making bodies and cultural institutions.”

The letter went on to denounce the government and the Ministry of Culture for their tactics in replacing Zdenka Badovinac, who until last year served as the director of Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana, a post she has held since 1993. In 2020, Badovinac was awarded the coveted Igor Zabel Prize. The jury recognised Badovinac for “her radical curatorial work and significant contributions as a writer and editor to international discourses on the geopolitics of contemporary art in Eastern Europe and global art history.” After advertising for her position at Moderna Galerija three times, the Ministry of Culture, which was responsible for finding her replacement, finally announced in November 2020 that a new interim director had been found, the poet and art historian Robert Simonisek. Finally, in April 2021, the government appointed a comparative literature historian and digital humanities academic, Aleš Vaupotič, as Moderna’s new director, causing further uproar and criticism that the government was effectively pushing out Badovinac to make way for a ministry appointee.

“What is happening in Slovenia is not an isolated phenomenon,” Badovinac says. “There are local versions of the same problem, but in the former socialist countries, almost all of them, reactionary forces are working against any and all positive sides of socialism, which (especially in former Yugoslavia) meant a society of solidarity, which today doesn’t exist anymore.” The new government has also targeted other prominent museum directors and institutions since assuming office last year. At the Museum of Architecture and Design (MAO), Matevž Čelik was replaced as director late last year too, despite having an excellent and well respected international track record. Having helmed MAO since 2010, Čelik also founded a pan-European Architecture platform called Future Architecture, and served as one of MoMA’s advisors for the Towards a Concrete Utopia exhibition.

According to Čelik, the new government is attempting to “subjugate culture in a totalitarian way.” He added that „the government is ignoring the prevailing values of Slovenian culture, which are anchored in traditions of rationalist humanism and ideas on the left side of the political spectrum.” The government, for it’s part, says that it is within it’s legal rights to replace museum directors and direct cultural policy as it sees fit. A representative for the Ministry of Culture said that it did not consider its actions populistic or right-wing. “We would like to highlight that the government led by Prime minister Janez Janša is not a ‘rightist’ government, it has two liberal left-wing coalition partners, both members of the ALDE European alliance. Slovenia only had homogenous governments when left-wing parties formed coalitions,” the government’s statement said.

However, it seems that the ruling party is keen on implementing populist reforms that threaten the longstanding cultural integrity and criticality of the country. Prior to the last election, Slovenia was involved in the transfer of millions of euros that nearly crippled Slovenia’s National Bank, the NLB, and with it the entire country’s finances. In addition, the SDS was embroiled in a health care scandal in 2020 involving the handling of government coronavirus contracts related to the procurement of personal protective equipment. The construction of a thermal dam in Slovenia also brought accusations of mismanagement and corruption, leading some to question whether the government is now using culture as a means of targeting critical, dissenting voices, many of whom oppose the government and accuse those in power of corruption.

The government also claimed that it was within its right to use the Ministry of Culture to depose directors it seems ideologically resistant. On the removal of museum directors, the government’s statement said that “it is a political process, but a process that requires regular transitions of power, which Slovenia sadly lacked for most of its independent history.” Speculation is however rampant that SDS will soon fold and new elections will take place in Slovenia in 2021. However, while there is hope that the situation will change and that the issues plaguing the Slovenian cultural sector will dissipate, the major issue seems to be with some of the EU’s other populist countries, including Hungary and Poland. For its part, the EU has attempted to reign in strong arm leaders who attempt to curtail artistic expressions. Last year, the European Commission threatened to impose sanctions on Poland for designating some cities “LGBTQ free zones,” while in other cases the EU has at numerous times threatened to withhold EU subsidies for member states who break the rules.

Nevertheless at an event called Europe Uncensored held last July, Slovenian Prime Minister appeared on stage alongside Hungarian leader Viktor Orban and Serbian President, Aleksandar Vučić. The trio appeared together to mark the 44th anniversary of the founding of the European People’s Party (EPP). At the event, Janša boldly proclaimed that “the main threat for [the] European Union and our future is cultural Marxism.” He stated his intention to form a “more united front”, in what he dubbed the “battle for western civilization.”

This has led some to speculate whether what is happening in Slovenia is part of a broader, EU-wide problem. According to the Polish museum director and curator, Małgorzata Ludwisiak, the situation in Slovenia is eerily familiar to the one in Poland. After being deposed of her role as the director of the CCA Ujazadowski Castle in December 2019, Ludwisiak says that what is happening to her colleagues in Slovenia mimics her own situation in Poland the year before.

And while Central Europe certainly has no shortage of irresponsible politicians to fuss over, artists continue to persist and develop new and interesting projects that not only critique existing power structures, but also to imagine new ones.

“Poland, Slovenia and other East-European countries are unfortunately not alone in their battle against far-right populist politics,” Ludwisiak says. “But in Eastern Europe, populism has an insidious shade: on the one hand inscribing itself into regime structures, which are historically very well known to us; and on the other, catalyzing and manipulating social emotions that arose in reaction to brutal capitalist transformations of the former social block after 1989.” Ludwisiak added that populism in central and eastern Europe is mostly driven by leaders who create purposeful divisions within society. “Populist politicians operate with a sense of tribalism, ‘cancelling’ curators or artists regardless of actual competency or achievements.” Both Ludwisiak and Badovinac are part of the International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art, or CIMAM, which is composed of the directors of major museums across the world. The organization advocates for museums and helps devise cultural policy for countries through policy white papers and lobby efforts.

Ludwisiak is part of CIMAM’s Museum Watch Committee, which aims to assist modern and contemporary art museum professionals deal with critical situations. “We are trying to carefully observe all irregularities in modern art museums’ governance around the world,” Ludwisiak said. The group intervenes by publishing statements, letters to authorities and/or alarming the local and international media. In some cases this pressure works, Ludwisiak says. “At the moment, CIMAM and ICOM are working together on a special project to find new ways to protect museums from irresponsible politicians.”

And while Central Europe certainly has no shortage of irresponsible politicians to fuss over, artists continue to persist and develop new and interesting projects that not only critique existing power structures, but also to imagine new ones. At the Fotopub Project Space, founded originally as a festival held in Novo Mesto, but now operational as a project space housed in a former brutalist gas station, new forms of art and collectivity are bridging the gap between different generations of artists in Ljubljana and abroad. One of the projects spearheaded by Fotopub founder, Dusan Smodej, in collaboration with Hana Ostan Ozbolt, director of the Ulay Foundation in Ljubljana, is the Academia Nuts programme, a year-long cultural education crash course and project designed and executed with an interdisciplinary group of young cultural practitioners, Lina Akif, Hannah Koselj Marušič, Lucija Ostan Vejrup, Lara Papov, Ema Radovan, Iza Štrumbelj Oblak, Lea Topolovec, Eva Žibert, who come from backgrounds as diverse as film, photography, performance and education.

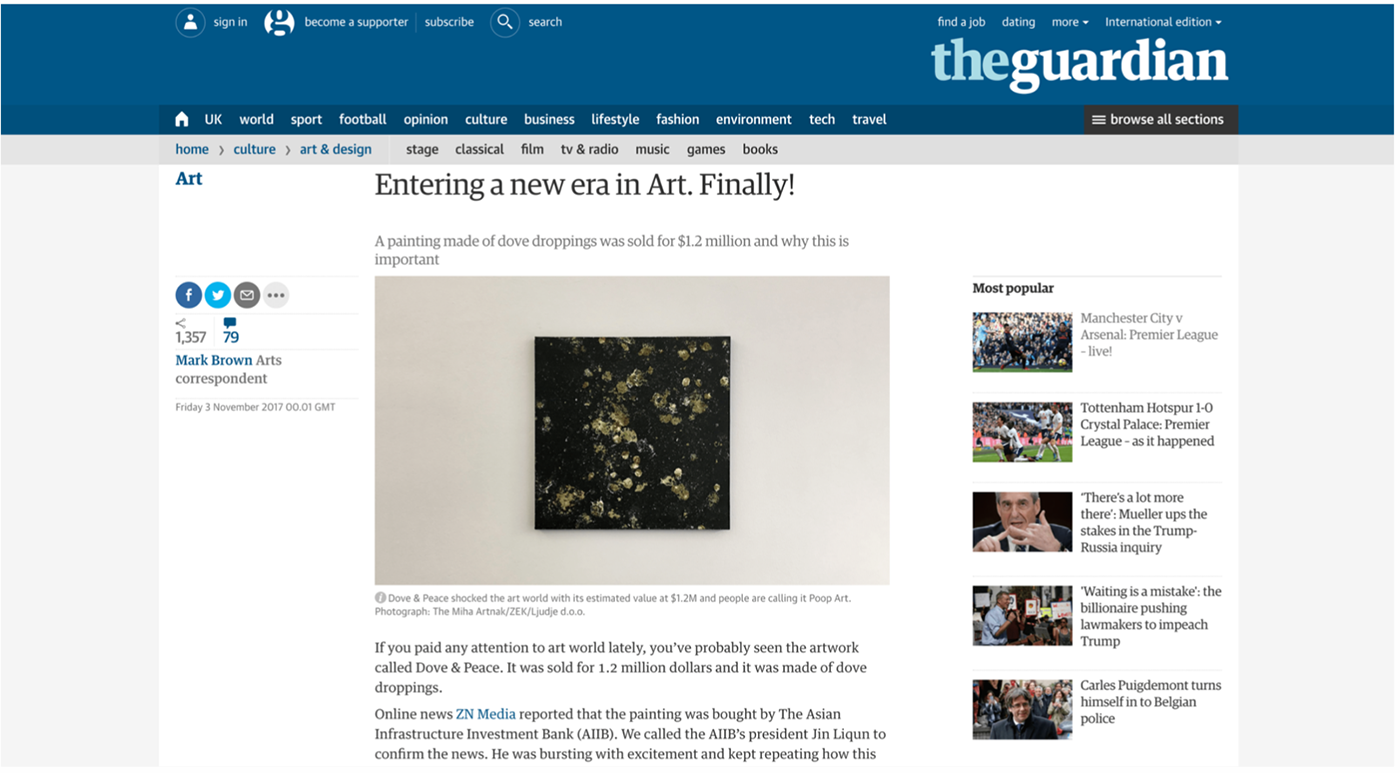

One of the most iconic artists of the young generation is Miha Artnak, a prankster whose work often combines humour with subtle social and political critiques. Artnak, who is based in Ljubljana, uses a variety of media and design thinking to critique our underlying trust and mistrust of the media. Touching on quite the nerve of some of the aforementioned financial scandals in Slovenia, in 2017 he pranked the Slovenian media into believing that he had sold an artwork for more than $1 million USD to a Chinese bank. The stunt netted him considerable notoriety, exhibited in the Museum of Architecture and Design Biennale’s BIO26, curated by Thomas Geisler and Aline Lara Rezende. The action prompted a wide-ranging conversation in the Slovenian media about the nature of art and PR pay-to-play driven cultural content.

Roman Uranjek remains one of Slovenia’s most active and politically conscious artists. As one of the founding members of not only NSK, but also IRWIN, a Slovenian painting collective founded in 1983 between Uranjek and Duan Mandi, Miran Mohar, Andrej Savski, and Borut Vogelnik, Uranjek has since forged a distinctive solo-career using various media like painting, collage and installation. While Uranjek’s early works with IRWIN and NSK were then synonymous with collectivity and the freewheeling punk art and graffiti scene of the 1980s, Uranjek has since developed a kind cartographic fascination with the rise and fall of former Yugoslavia. Since 2002, he has been drawing, collaging or painting at least one image of a cross per day. The cross, for Uranjek, has a proto-dystopian symbolism, on the one hand relating to heaven, utopia and redemption, whilst on the other signifying death, torture and self-flaeggelation, the rise and fall of empires, but also the ideologies that political and religious symbols inhabit.

The intermedia artist Maja Smekar is also one of Slovenia’s most interesting and promising. Her project “K-9_topology” won Prix Ars Electronica 2017 in the Hybrid Art – Golden Nica category. The Prix Ars Electronica is one of the most important awards in the world for creativity and a pioneering spirit in the field of digital media. The installation has been made for the CyberArts 2017 – Prix Ars Electronica at the OK Offenes Kulturhaus – Center for Contemporary Art Linz as a part of Ars Electronica festival 2017, consisted of the artist using her body to interface between the canine and human worlds. For her project “Hybrid Family” in 2016, the artist participated in three-month period of seclusion with her dogs, stimulating her pituitary glands with systematic breastpumping to release the hormone prolactin, which followed a diet rich in galactogogues to promote lactation, allowing her to essentially breastfeed her own dogs. The results, according to Smekar, “led to an increase in empathy and my personal resistance to the cynicism of the zeitgeist.”

name: is another artist whose work defies easy categorization, but whose conceptual approach to design, art and public space tackle difficult, often timely political subjects. In Ping Pong (2018), exhibited parallel to the Fotopub Festival in Novo Mesto, name: installed a ping pong table on 6 foot high stilts, which the audience was able to climb and play. Alongside the installation, there was a video of name: playing ping pong on the same heightened table, only installed on the Slovenian border with Croatia, the project commenting on the nature of borders across the entire former-Yugoslavia.

In December 2020, name: installed a large digital clock above the Fotopub Project Space. The clock, reminiscent of the iconic digital clock on top of Slovenia’s largest building, TR3, counts down to 9:00PM – the country’s corona-virus curfew, which has been in place now running on 12 weeks (at the time of writing in January 2021). As the clock strikes 9:00 PM, a siren sounds off into the night, reminding those within its vicinity of the country’s stay-at-home orders, responsive to the country’s handling of the coronavirus, but also to the psychological nature of Marshall law itself, where thinking has been replaced with conformity, freedom with control, and collectivism with individual sovereignty. A stark reminder that in the midst of the pandemic, the idea of freedom itself is being retooled and rethought, but also that artists, forever curious and inquisitive in nature, will — despite government decree — forever question and probe further.