Zostałem fotografem propagandy. Rozmowa z Rafałem Milachem / I Became a Propaganda Photographer. Conversation with Rafał Milach

Leszek Jażdżewski: Jak to się zaczęło z tymi Winnersami?

Rafał Milach: Pojechałem na Białoruś z pomysłem na historię o moich krewnych. To miał być bardzo intymny i osobisty temat, ale już podczas pierwszej podróży zainteresowało mnie coś innego. Moją uwagę przykuła sterylność przestrzeni publicznej. W pieczołowitym utrzymywaniu czystości było coś obsesyjnego, wykraczającego poza zwykłą dbałość o otoczenie. Honorowe miejsce na głównych placach miast, miasteczek i wsi najczęściej zajmowała tzw. doska paciota, czyli tablica chwały.

Był to panel z portretami najbardziej zasłużonych obywateli wśród lokalnych społeczności: najlepszych pracowników, urzędników, działaczy etc.

Takich przodowników pracy, wzorowych obywateli?

Tak, to byli tacy lokalni bohaterowie, naznaczani przez miejscowe władze, od kierownictwa zakładu po zarząd gminy czy inne oficjalne struktury. Najczęściej były to nowo wybudowane lub odnowione konstrukcje. Nie jakieś tanie panele, deski czy ścianki, tylko specjalnie zaprojektowana mała architektura, często o dość ekstrawaganckiej formie, obłożona kafelkami lub innym materiałem; wszystko oczywiście czyste, błyszczące i bardzo reprezentacyjne.

I to mnie zafascynowało. Stwierdziłem, że stworzę swoją listę tego, co najlepsze, tego, co władze promują jako idealny model społeczeństwa. Najlepsi z najlepszych. Oficjalnie wybrani, oficjalnie nagrodzeni.

Ci, których system chce zaprezentować jako swoją wizytówkę?

Tak. Kryterium było takie, że to musi być ktoś, kto jest oficjalnie nagrodzony, kto ma dyplom. Niektórzy z moich bohaterów pojawili się również na doskach paciota. W ten sposób zostałem fotografem oficjalnej białoruskiej propagandy, akredytowanym przy Ministerstwie Spraw Zagranicznych.

Czy miałeś nad tym kontrolę? Nie było tak, że oni podsuwali kogoś?

To byłaby idealna sytuacja! Ponieważ ja jako twórca chciałem się jak najbardziej wycofać z procesu kreatywnego. Chciałem sprowokować sytuację, gdzie będę jak najbardziej kontrolowany i podatny na sugestie. Chciałem oddać jak najwięcej kontroli na zewnątrz. Było to uzasadnione, ponieważ moim zamiarem nie było nawiązywanie osobistych relacji z ludźmi, których fotografowałem. Interesowała mnie jedynie ta konkursowa fasada.

Czy robiąc kolejne zdjęcia, stając się propagandowym fotografem, dowiedziałeś się czegoś nowego, czego nie wiedziałeś wcześniej o tym systemie?

Przede wszystkim chciałem świadomie stać się częścią tego mechanizmu. I to było dla mnie nowe doświadczenie. Kolejnym ważnym aspektem mojej pracy było obnażenie instrumentalnego podejścia systemu do jednostki, co samo w sobie nie jest specjalnie odkrywcze, natomiast empiryczne doświadczenie tego procesu było czymś, co zmieniło moją fotograficzną strategię na kilka następnych lat. Ten projekt składa się z pojedynczych historii, ale funkcjonuje jako całość. Dla mnie to jest pewna kolekcja.

Czyli możesz podmienić zdjęcie czy osobę na inne?

W sensie utrzymania spójności przekazu tak, oczywiście. To brzmi cynicznie, ale historia pojedynczego człowieka, przedmiotu lub miejsca nie ma tu większego znaczenia w kontekście hierarchii, ponieważ swoją uwagę skupiam na systemie, a nie na indywidualnych motywach. To, że stałem się częścią systemu na własne życzenie, było o tyle ważnym gestem, że przypomniało mi o powszechnym uwikłaniu w machinę propagandową. Niezależnie od tego, po której stronie stoimy.

To jest dla mnie bardzo ciekawe. Ten tytuł: czy ty go traktujesz ironicznie? Czy ci ludzie na serio uważają się za zwycięzców?

Niektórzy podchodzili do tego bardzo poważnie, niektórzy z przymrużeniem oka. Nie wszystkie konkursy były traktowane serio. Niektórzy nawet nie wiedzieli, że są zwycięzcami. Jestem pewien, że większość moich bohaterów, z kilkoma wyjątkami, brała udział w konkursach dobrowolnie.

Nie są ofiarami systemu?

Nie, oni przeważnie są częścią tego systemu, najczęściej w sposób bierny. Czasami wiąże się to z jakimiś drobnymi nagrodami czy bonusami pieniężnymi. Myślę, że w każdym z nas jest taka głęboka potrzeba bycia docenionym, bycia zauważonym, szczególnie w lokalnej społeczności. Pytanie, kto jest największym beneficjentem takiego układu. Ale czasem zdarzają się pęknięcia.

Na Białorusi po raz pierwszy świadomie stałem się uczestnikiem machiny propagandowej i to mnie w jakiś sposób zafascynowało.

Miałem sfotografować najlepszego oracza. To się działo na głębokiej prowincji i dojechanie tam z Mińska samochodem zajęło mi kilka godzin. Kiedy w końcu znalazłem się w budynku administracji kołchozu, przyszedł ten najlepszy oracz i powiedział, że on w zasadzie nie chce być sfotografowany, i odszedł. Jego przełożony był w szoku, nie wiedział co ma zrobić, w tym momencie ten system się zawalił. Ja w pierwszym momencie byłem poirytowany odmową, ale później zdałem sobie sprawę, że to sytuacja raczej optymistyczna. Na pocieszenie sfotografowałem paprotkę, znajdującą się w pomieszczeniu, w którym miałem sportretować oracza. Jego sprzeciw okazał się być jedynym zakłóceniem w systemie podczas realizacji całego projektu. Zarejestrowałem ponad setkę zwycięzców, ale ta jedna sytuacja pokazała, że istnieje jakieś alternatywne rozwiązanie. Nie wiem, jakie były konsekwencje postawy oracza.

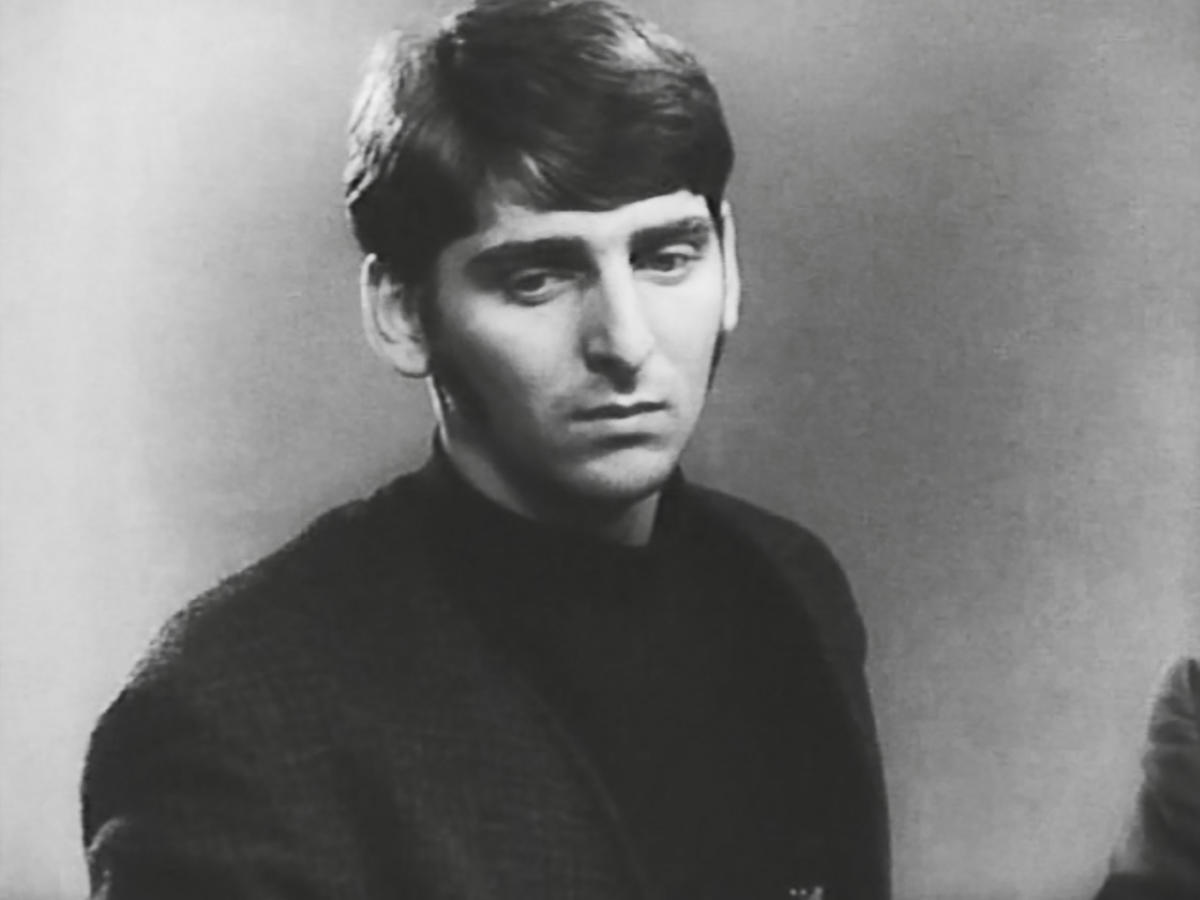

Rafał Milach, z cyklu The Winners (2010-2013),

Krejwańcy, Białoruś, 2013 / Rafał Milach, from The Winnersseries (2010-2013)

Kreyvantsy, Belarus, 2013

Czy realizując ten projekt, myślałeś o sobie jako o takim „fotografie systemu”, czy zostawiałeś sobie przestrzeń autonomii w jego ramach?

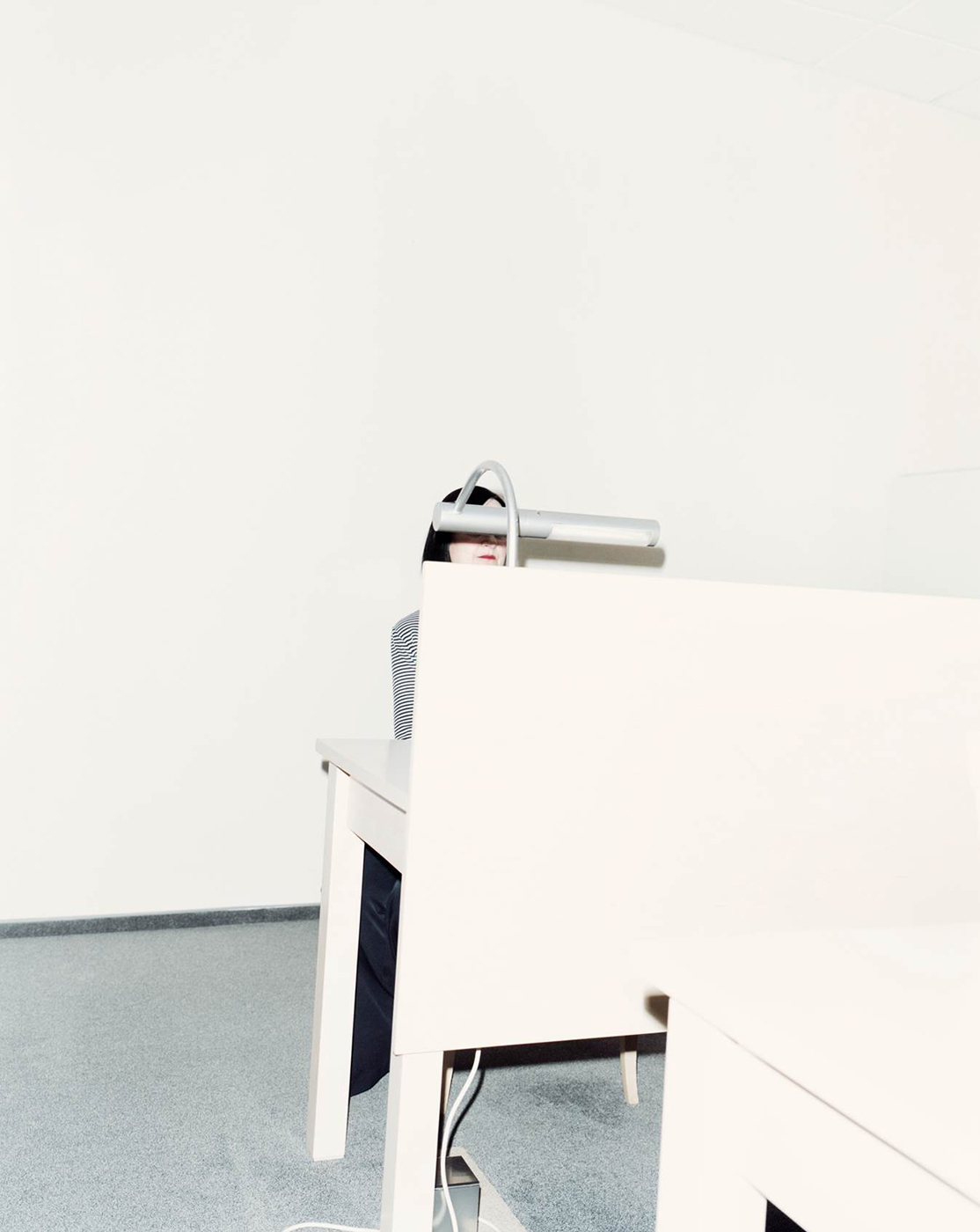

Przeważnie starałem się korzystać z tego, co dostałem, natomiast w wielu sytuacjach okazywało się, że nawet w ramach tej samej przestrzeni, która była mi udostępniana, mogłem poszukać jakiegoś drobnego pęknięcia, jakiejś luki. Tu ktoś trzyma jakąś zasłonkę, tu jest jakaś nie do końca piękna ściana.

Co sprawiło, że od dość dosłownych Winnersów przeszedłeś do bardziej abstrakcyjnego konceptu…?

Na Białorusi po raz pierwszy świadomie stałem się uczestnikiem machiny propagandowej i to mnie w jakiś sposób zafascynowało. Skrystalizował mi się schemat gry między społeczeństwem a władzą i ciekawy byłem, jak to wygląda w innych miejscach, dlatego zacząłem szukać podobnych schematów w Gruzji, Azerbejdżanie, a później w Polsce. Spuścizna po byłym prezydencie Micheilu Saakaszwilim, kontrowersyjny klimat nadużyć finansowych i politycznych, w którym zakończył swoje rządy krajem, stały się inspiracją do tego, nad czym pracowałem w Gruzji. Skupiłem się głównie na ekstrawaganckich działaniach modernizacyjnych, które zainicjował, a które zostały wstrzymane albo nigdy nie doszły do skutku, kiedy musiał uciekać z kraju po przegranych wyborach. To było chodzenie po śladach, próba zrekonstruowania świata, który został z różnych powodów, ale głównie politycznych, niedokończony. Trzeba zaznaczyć, że podczas wspieranych przez świat zachodni reform i modernizacji Gruzja cieszyła się największą liczbą więźniów politycznych na całym obszarze poradzieckim.

Czym są te sfotografowane przez ciebie abstrakcyjne figury?

W sąsiadującym z Gruzją Azerbejdżanie fotografowałem Centra im. Hejdara Alijewa – byłego pierwszego sekretarza partii radzieckiego Azerbejdżanu i pierwszego przywódcy kraju po upadku ZSSR. Te obiekty znalazłem w jednej ze szkół szachowych. Były to pomoce naukowe, które dotyczyły zagadnienia iluzji optycznej. Ich umiejscowienie w budynkach, które budują kult osoby byłego prezydenta pozwoliło na przesunięcie ich znaczenia. Stały się dla mnie metaforą mechanizmów propagandowych, które również kamuflują rzeczywistość, zakłócając naszą percepcję. I te niewinne obiekty nagle zyskały dla mnie zupełnie nowe znaczenie.

Utrwalasz obiekty służące demaskowaniu iluzji w centrum propagandy, którego celem jest budowa społecznej iluzji niemożliwej do zdemaskowania. Analogia dostępna raczej dla niewielu?

Jedynymi ludźmi, których spotykałem w centrach Alijewa, byli pracownicy tych instytucji. Wyjątkiem była grupa dzieci szkolnych przygotowująca przedstawienie na cześć azerskiej interwencji militarnej w Górskim Karabachu, która miała miejsce kilka dni wcześniej. Więc te bogato wykończone kompleksy były praktycznie niewykorzystywane, takie przynajmniej odniosłem wrażenie.

Jestem coraz bardziej świadomy swojego uwikłania w różne konteksty, ostatnio bardziej polityczne, które wcale nie są oderwane od konsekwencji, jakie ponosi społeczeństwo.

Ale nawet gdyby przedmioty, które tam znalazłem, były używane, wątpię, by ktoś przypisał im inne znaczenie, odmienne od tego, dla którego zostały stworzone. To ja jako artysta wprowadzam to przesunięcie znaczeniowe i buduję metaforę.

Jak to doświadczenie z przestrzeni poradzieckiej przygotowało cię do zmierzenia się z Polską, z przestrzenią, która jest tak oczywista jak powietrze, którym oddychasz? Jak bawić się w demaskatora będąc częścią tego systemu, czy można z wewnątrz w ogóle dostrzec jego naturę?

To jest zdecydowanie najtrudniejsza rzecz, z którą się do tej pory mierzyłem. Z jednej strony znam realia i tło, co w pewnym sensie uprawomocnia mnie do tego, żeby to komentować. Z drugiej strony, jak mówisz, jest to tak codzienne i tak oczywiste, że czasami ciężko znaleźć to pęknięcie, a czasami tych pęknięć jest tak dużo, że nie wiesz gdzie zacząć.

Czy u nas ważniejsze od ściskania ręki ministrowi nie jest to, kogo reklama, media przedstawiają jako atrakcyjnych i ciekawych? Czy ty jako wzięty twórca nie jesteś właśnie bohaterem systemu?

Z jednej strony biorę świadomy udział w komentowaniu lub demaskowaniu różnych mechanizmów systemowych gdzieś daleko, ale jestem pewien, że pozycja, którą zajmuję, opinie, które wygłaszam, mogą wpisać się w jakąś myśl propagandową, niekoniecznie poradziecką. Jestem coraz bardziej świadomy swojego uwikłania w różne konteksty, ostatnio bardziej polityczne, które wcale nie są oderwane od konsekwencji, jakie ponosi społeczeństwo. Polaryzacja, zawłaszczanie symboli, tworzenie nowych mitów, przesuwanie znaczeń to są rzeczy, z którymi mamy do czynienia na co dzień.

Ciekawe, czy czujesz się tym poruszony, nie byłeś artystą kojarzonym z jakimiś zbiorowymi uniesieniami.

Polityka jako taka nigdy mnie nie interesowała i dalej nie interesuje. Ale czasy mamy takie, że nawet niewinne gesty mają znaczenie polityczne. Ten sposób myślenia narasta we mnie od momentu, kiedy zacząłem pracować na Białorusi. Te niewinne gesty, które zaprzęgam w artystyczne projekty, zyskują polityczne znaczenia przez otoczenie, w jakim się znajdują, chociaż procesy, o których opowiadam, są raczej konsekwencjami społecznymi ideologii niż komentarzem bezpośrednio uwikłanym w politykę. W Polsce, mam ostatnio wrażenie, że stałem się częścią jakiegoś strasznego komiksu i prawdopodobnie to jest moja projekcja rzeczywistości, ale karykaturalność i absurdalność niektórych sytuacji wytwarza we mnie poczucie jakiejś równoległej rzeczywistości. W związku z tym postanowiłem stworzyć komiks. Fragment wystawy komentujący Polskę jest oparty na rysunkach, które powstały na bazie moich lub zapożyczonych fotografii. Zacząłem szukać w polskiej przestrzeni czegoś, co ma w sobie dużą dozę propagandy, jakiejś symboliki czy budowania nowego mitu, ma jednocześnie jakiś wymiar polityczny, jest aktualne. Najbardziej ewidentnym odniesieniem wydawała się być katastrofa smoleńska. Nagle Tupolew 154 stał się symbolem narodowym. Niewinny obiekt zyskał nowe znaczenie ideologiczne. Sprawa katastrofy do dzisiaj owiana jest tajemnicą, więc znalazłem tę modelową sytuację, której szukałem.

Jaka będzie fabuła tego komiksu o Tupolewie?

To nie będzie jakaś fabularna historia, będzie łączyć w sobie kilka różnych wątków. Z jednej strony odnosi się do zdjęć, które wykonałem na jednej z miesięcznic smoleńskich, gdzie kilkuosobowa grupa podczas obchodów rekonstruuje wrak samolotu.

Tą sytuację zestawiłem z plastikowym modelem samolotu Tu-154 w skali 1:144; takim modelem, który każdy może sobie kupić i posklejać. Kolejny niewinny gest obarczony politycznym kontekstem. I następną, trzecią warstwą tego komiksu będą wybrane kadry z filmu Smoleńsk w reż. Antoniego Krauzego. Jest to też jakaś wersja rekonstrukcji tego wydarzenia. Te wszystkie elementy przeplatając się ze sobą, tworzą pewien obraz katastrofy, który lansowany jest przez obecne władze.

A czy ty czujesz, że w tym wypadku też dokonujesz takiego gestu demaskacyjnego poprzez zestawienie rekonstrukcji z tym modelem?

Jedyne, co robię to przystawiam lustra. Ale jest to gest zdecydowanie krytyczny. Z jednej strony nie podoba mi się polityczny wymiar tego tragicznego wydarzenia oraz fakt, że staje się ono jednym z narzędzi do polaryzacji społeczeństwa.

Czy myślisz – już tak zupełnie na sam koniec − że sztuka, ty jako artysta, masz jakieś narzędzia, żeby się przez tę ścianę systemu przebić na drugą stronę i go zdemaskować?

Działania w obszarze sztuki są przeważnie dosyć niszowe, ale nie zmienia to faktu, że zadaniem artysty jest komentowanie i zwracanie uwagi na istotne kwestie. Powstają koalicje artystów, którzy są zaangażowani politycznie. Wręcz wycofują się ze sztuki na rzecz aktywizmu. Artyści mają narzędzia do komentowania tego, co się dzieje, więc powinni je wykorzystywać.

A to jest twoja droga? Nie czujesz, że tracisz jakąś część siebie, wchodząc tak jednoznacznie w spór?

Nigdy nie podchodziłem do sztuki jako do sytuacji czysto estetycznej. Podziwiam wielu artystów, którzy tworzą, izolując się od rzeczywistości, ale zdecydowanie bliżej mi do postaw zaangażowanych społecznie. Fotografia dobrze sprawdza się na tym polu, chociaż w niektórych przypadkach jest zbyt realistyczna. Stąd pomysł na komiks, który jest częścią wystawy. Forma rysunkowa, chociaż figuratywna i realistyczna, zdejmuje publicystyczny wymiar obrazu, którym obciążone były fotografie, jakie zrobiłem.

Musiałeś to przetworzyć?

Tak. Musiałem posklejać tych kilka warstw, żeby to nie stało się zbyt prostym komunikatem. Nie jestem satyrykiem i pracuję powoli. Czułem, że…

… że musisz niejako pójść trochę do innego medium, niż to, w którym pracowałeś w ostatnim czasie?

Tak. Chociaż medium, pomimo tego, że czuję się przywiązany do fotografii, ma dla mnie funkcję zdecydowanie podrzędną wobec historii.

Rozmowa pochodzi z katalogu towarzyszącemu wystawie Rafał Milach Odmowa / Refusal w Atlasie Sztuki.

Leszek Jażdżewski: So, how did your Winners begin?

Rafał Milach: I went to Belarus with the notion of my relatives’ history in mind. It was supposed to be an extremely intimate and personal theme, but during my first trip, something else captured my interest. What caught my attention was the sterility of the public space. There was something obsessive about the solicitously maintained cleanness; it went beyond any normal care for the surroundings. And, in the main squares, the cities and the towns, a focal point was what are known as Doska pochyota, 'Boards of Honour’, in other words, panels featuring the portraits of the most worthy citizens in the local community; the best workers, the best officials, the best activists, etcetera.

Like 'shock workers’ and 'exemplary citizens’?

Yes. They were these local heroes, designated by a range of local authorities, from workplace managers to the commune council and other official bodies.

The display structures were most frequently newly built or renovated. Not just any cheap panels, planks of wood or sidings, but small architectural works, specially designed and often quite extravagant in form, laid with tiles or some other material and, naturally, all of them clean, gleaming and extremely stately.

And that fascinated me. I stated that I’d make a list of the best, of what the authorities are promoting as the ideal social model. The best of the best. Officially selected and officially awarded recognition.

The ones the system wants to present as its leading lights?

Yes. The criterion was that it had to be someone who’s been officially recognised and has a certificate. Some of my central figures had also appeared on the 'boards of honour’. And that’s how I became a photographer of official Belarusian propaganda, accredited by the Minster of Foreign Affairs.

Did you keep control over what you did? Didn’t they happen to push anyone forward?

That would’ve been the ideal situation! Because, as an artist, I wanted to retreat as far as I could from the creative process. I wanted to provoke situations where I’d be under as much control and as susceptible to suggestion as was possible. I wanted to surrender all the control I could to outside forces. That was justified, because my intention wasn’t to establish a personal relationship with the people I was photographing. All that interested me was the competitive façade.

Rafał Milach, z cyklu The Winners (2010-2013),

Mińsk, Białoruś, 2013 / Rafał Milach, from The Winnersseries (2010-2013),

Minsk, Belarus, 2013

As you took each successive shot, as you became a propaganda photographer, did you find out something new about the system, something you hadn’t known before?

First and foremost, I consciously wanted to become a part of that mechanism. And that was a new experience for me. Another important aspect of the work was laying bare the system’s instrumental approach to the individual. In itself, that’s not especially revelational, but the empirical experience of the process was something that changed my photographic strategy for the next few years. The project is composed of individual stories, but it functions as a whole. To me, it’s a collection.

In other words, you can swap one photo or person for another?

In the sense of retaining the coherence and cohesiveness of the message, yes, of course. It sounds cynical, but the story of any one person, object or place doesn’t have a greater meaning in the hierarchical context, because my attention was focused on the system and not on individual motifs. The fact that I became a part of that system at my own wish was a gesture of enough importance to remind me of our universal entanglement in the propaganda machine. No matter which side we’re on.

I find that very interesting. The title… is your view of it ironic? Do those people seriously consider themselves to be winners?

Some of them took it extremely seriously and some of them took it with a pinch of salt. Not all the competitions were treated as earnest affairs. Some of the people didn’t even know they were winners. I’m certain that, with a few exceptions, my central figures competed of their own accord.

Not as victims of the system?

No. In the main, they’re part of that system, most often a passive part. It’s sometimes connected to small prizes or financial bonuses. I think all of us have a profound need to be appreciated, to be noticed, particularly within the local community. The question is this; who benefits the most from that kind of set-up?

But sometimes, a crack occurs. I was supposed to photograph the best plougher.

It was taking place deep in the provinces and it took me several hours to get there by car from Minsk. When I finally made it to the administrative building on the kolkhoz[1], the best plougher came up to me, said that he didn’t want to be photographed and walked off. His supervisor was in a state of shock, he had no idea what he should do. At that moment, the system foundered. To start with, I was annoyed by the plougher’s refusal, but then I realised that it was more of an optimistic situation.

I consciously became a participant in a propaganda machine for the first time in Belarus and, in a way, that fascinated me.

By way of consolation, I took some photos of the fern in the room where I’d been supposed to shoot the portraits of the plougher. That turned out to be the sole disruption that ruffled the system during the entire project. I took more than a hundred photographs and only that one situation showed that a different solution does exist. I don’t know what the consequences of the plougher’s attitude were.

When you were working on the project, were you thinking of yourself as a 'system photographer’ or did you leave yourself an autonomous space within that framework?

On the whole, I tried to make use of what I was given, but in a great many situations it turned out that, even within the framework of the very space that was made available to me, I could seek out some kind of small crack, some kind of gap. Someone holding some kind of curtain here, some kind of not entirely lovely wall there.

Which meant that you shifted from the fairly literal Winners to a more abstract concept…?

I consciously became a participant in a propaganda machine for the first time in Belarus and, in a way, that fascinated me. The pattern of the game played between society and the authorities crystallised for me and I was interested in what it’s like in other places, which is why I began searching for similar patterns in Georgia and Azerbaijan and, later on, in Poland.

The legacy left by former president Mikheil Saakashvili, the controversial atmosphere, the financial and political abuses that he ended his rule of the country with became the inspiration for what I worked on in Georgia. I focused primarily on the extravagant modernisation work which he initiated and which came to a stop or would never be accomplished once he had to flee the country after he lost the election. It was following the clues, an attempt to reconstruct a world that, for various reasons, but mainly for political ones, had been left uncompleted. I should point out that, during the reforms which were supported by the Western world, Georgia boasted the highest number of political prisoners in the entire post-Soviet region.

What are the abstract figures you’ve photographed?

Next door to Georgia, in Azerbaijan, I photographed a number of centres named after Heydar Aliyev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan and the country’s first leader after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

I found the objects in one of the chess schools; they were teaching aids related to the puzzle of optical illusion. The fact that they’d been housed in buildings where the cult of the former president is being built made a shift in their meaning possible. To me, they became a metaphor for propaganda mechanisms, which also camouflage reality and disrupt our perception. And suddenly, those innocent objects obtained an entirely new meaning for me.

You create lasting images of objects serving to unmask illusions in a propaganda centre designed to build social illusions that are impossible to unmask. An analogy that’s really more accessible only to a few?

The only people I met in the Aliyev centres were the employees of those institutions. The sole exception was a group of schoolchildren who were preparing a performance in honour of the Azerbaijani military intervention in Nagorno-Karabakh, which had taken place just a few days before. So those richly finished complexes were practically unused; at any rate, that’s the impression

I had. But even if the objects I found there were used, it’s doubtful that anyone would attribute a significance to them other than the one they were created for.

I, as an artist, am the one carrying out that shift in meaning and building the metaphor.

How did your experience in the post-Soviet space prepare you to tackle Poland, with a space that’s as evident to you as the very air you breathe? How does one play the unmasker as a part of the system? Is it possible to discern its nature at all from the inside?

It’s definitely the most difficult thing I’ve tackled so far. On the one hand,

I know the realities and the background, so, in a sense, that authorises me to comment on it. On the other hand, as you say, it’s so everyday and obvious that sometimes it’s hard to find the cracks and sometimes there are so many of them that you don’t know where to start.

In Poland, aren’t the people presented as attractive and interesting by the adverts and the media more important than shaking hands with government ministers? As a popular artist, aren’t you actually a hero of the system?

On the one hand, I consciously take part in commenting on, or unmasking, various systemic mechanisms from a distance, but I’m certain that the position I take and the opinions I express could make their mark in some kind of propagandist thinking, not necessarily post-Soviet. I’m becoming more and more conscious of my involvement, in various contexts, more political of late, which aren’t at all disconnected from the consequences borne by society. Polarisation, the appropriation of symbols, the creation of new myths and the shifting of meanings are things we’re dealing with on a daily basis.

It’s interesting that you feel impelled by that. You haven’t been an artist who’s associated with any kind of collective exultation.

Politics as such has never interested me before and it still doesn’t. But we’re living in times when even innocent gestures have a political meaning. That way of thinking began building up in me from the moment I started working in Belarus. The innocent gestures I harness in my artistic projects obtain political meanings through the environment I find myself in, even though the processes I’m addressing are more the consequence of social ideologies than a commentary directly involved in politics.

I’ve recently had the impression that, in Poland, I’ve become part of some kind of horrible comic and in all likelihood that’s my projection of reality, but the caricatural grotesquerie and absurdity of some situations generates a sense of a parallel reality in me.

All I’m doing is holding up a mirror. But it’s definitely a critical gesture.

Because of that, I decided to create a comic. The section of the exhibition commenting on Poland is rooted in drawings created on the basis of photographs, either mine or borrowed. I began searching the Polish space for something which contains a large measure of propaganda, some kind of symbolism or the building of a new myth and which, at the same time, has a political dimension, it’s topical.

The most obvious point of reference turned out to be the Smolensk air disaster[2]. A Tupolev 154 became a national symbol. An innocent object obtained a new ideological meaning. The matter of the air disaster remains wreathed in mystery to this day, so I found the model situation I’d been looking for.

What will the storyline of the Tupolev comic be?

It isn’t going to be a fiction-type story. It’s going to connect several different threads. On the one hand, it refers to the photographs I took at one of the monthly Smolensk commemorative gatherings, where there was a small group of people reconstructing the wreck of the aircraft during the proceedings.

I juxtaposed that situation with a 1:44-scale model of a Tu-154, the kind anyone can buy and assemble. Another innocent gesture burdened with a political context.

And the next, third level of the comic is going to be selected stills from Antoni Krauze’s film, Smolensk. That’s also a version of a reconstruction of the event. All those elements interweaving together create a certain image of the disaster which the current authorities are thrusting to the fore.

And do you feel that, in this case, you’re also performing a gesture of unmasking by juxtaposing the reconstruction with that model.

All I’m doing is holding up a mirror. But it’s definitely a critical gesture. On the one hand, I dislike the political dimension of that tragic event and the fact that it’s become one of the tools for polarising society.

And here, at the absolute end, do you think that art, that you, as an artist, have any tools to break through to the other side of the wall of the system and unmask it?

On the whole, activities in the sphere of art are fairly much niche activities, but that doesn’t change the fact that the artist’s task is to comment and turn people’s attention to essential matters. A coalition of artists who are politically engaged is forming. They’re quite simply withdrawing from art in favour of activism. Artists do have the tools to comment on what’s happening, so they should use them.

And is that your path? Don’t you feel that you’re losing a part of yourself by entering into the dispute so unequivocally?

I’ve never approached art as I’d approach a purely aesthetic situation. I admire the many artists who create by isolating themselves from reality, but stances of social engagement are definitely closer to my heart.

Photography works well in that field, although it’s overly realistic in some cases. Hence the idea for the comic, which is part of the exhibition. Although the form, drawing, is figurative and realistic, it strips away the journalistic dimension of the image that weighed down the photographs I took.

You had to transform it?

Yes. I had to stick those few layers together so that it didn’t become an overly simple message. I’m not a satirist and I work slowly. I felt that…

…that, somehow, you had to go for a medium that was slightly different from the one you’d been working in recently?

Yes. Although, despite the fact that I feel attached to photography, as I see it, the medium definitely has a subordinate function in the face of history.

English translation by Caryl Swift.

A conversation is a part of the catalogue of the exhibition Rafał Milach Refusal at Atlas Sztuki.

[1] A type of collective farm.

[2] The air disaster occurred on 10th April 2010. A Polish Air Force Tupolev Tu-154 crashed while carrying the President of the Republic of Poland, his wife, senior military personnel and clergymen, significant past and present political figures and other highly placed members of the country’s elite. The passengers were travelling to mark the seventieth anniversary of the Katyn Massacre, which was carried out not far from Smolensk, in Russia. The plane crashed as it was coming in to land. All ninety-six people on board were killed. On the tenth day of every month since then, a commemorative Mass is celebrated in Warsaw. The service is followed by a public assembly outside the presidential palace.

Przypisy

Stopka

- Osoby artystyczne

- Rafał Milach

- Wystawa

- Odmowa / Refusal

- Miejsce

- Atlas Sztuki, Łódź

- Czas trwania

- 12.05 - 18.06.2017

- Strona internetowa

- atlassztuki.pl