Stalowe abstrakcje we wzorcowym mieście / Steel abstract forms in a model city

For English version scroll down

PL

Martyna Nowicka: Dlaczego w niewielkim mieście nad Dunajem, na brzegu rzeki mieści się park, pełen ogromnych, abstrakcyjnych rzeźb ze stali?

Annamaria Nagy: Te rzeźby są ściśle związane z historią samego miasta i z biennale, które odbywało się tu przez niemal trzydzieści lat. Na pierwszy rzut oka mogą one dziwić, zwłaszcza, jeśli do Parku Rzeźby trafimy przez socrealistyczną część Dunaújváros, ale w gruncie rzeczy wyrastają z tych samych socjalistycznych założeń, co całe miasto.

Wszystko tutaj zaczęło się od pomysłu, że na Węgrzech potrzebna jest huta stali. Przed II wojną światową Węgry były głównie krajem rolniczym – są tu naprawdę dobre warunki klimatyczne i żyzne gleby, uprawy od zawsze się udawały. Po 1945 roku postanowiono z Węgierskiej Republiki Ludowej uczynić kraj węgla i stali. Sprawę nieco utrudniał niemal całkowity brak złóż naturalnych. W pierwszej wersji huta, a także otaczające ją idealne miasto, ośrodek przemysłu metalurgicznego, miała znaleźć się zdecydowanie bliżej granicy z Jugosławią. Ze względów strategicznych przeniesiono ją tutaj, czyli niemal dokładnie na sam środek kraju. Transportowi surowca z odległych gór miał służyć Dunaj, ale szybko okazało się, że to problematyczne – prawie zawsze jego poziom był za wysoki czy za niski, nurt zbyt wartki lub zbyt powolny. W każdym razie, plany lepiej wyglądały na papierze.

Malarze i rzeźbiarze dostawali w Dunaújváros mieszkania i pracownie, a do tego płacono im pensje. W zamian za to tworzyli na rzecz miasta, a do tego mieli obowiązek angażować się w życie lokalnych społeczności, prowadzić kluby artystyczne.

Dunaújváros nie wygląda jednak całe jak socrealistyczne miasto. Nie tylko park rzeźby sprawia wrażenie, jakby był z innego porządku.

To prawda. Pierwszym architektem, który zabrał się za planowanie i budowę miasta, był Tibor Weiner. Wykształcony w Bauhausie, pracował w Związku Radzieckim, w Bazylei i Paryżu, w trakcie II wojny światowej wyjechał do Chile. Wrócił, skuszony perspektywą budowy miasta od zera. Te pierwsze projekty były prawdziwie modernistyczne, ale partia szybko z nich zrezygnowała – ten modernizm nie licował z koncepcją miasta Stalina. Nie zmieniło się za to podejście do mieszkańców Sztálinváros – to od początku było bardzo bogate miasto, model dla innych socjalistycznych miast. I chociaż zgodnie z pierwotnymi założeniami miało tu mieszkać tylko 20 tysięcy ludzi, zbudowano im nie tylko szpitale i stołówki, ale także domy kultury, kino i teatr. W cieniu fabryki miało rosnąć wzorcowe miasto, którego mieszkańcy żyją idealnie socjalistycznym życiem.

Czyli kultura miała od początku pełnić ważną rolę w życiu mieszkańców? Na jaką dziedzinę artystyczną kładziono największy nacisk?

Od początku w centrum zainteresowań władz była kultura wysoka. Właśnie dlatego nie tylko wprowadzano tu dzieła sztuki i budowano infrastrukturę dla życia kulturalnego, ale również starano się zachęcać artystów do przeprowadzki do Dunaújváros. Malarze i rzeźbiarze dostawali tu mieszkania i pracownie, a do tego płacono im pensje. W zamian za to tworzyli na rzecz miasta, a do tego mieli obowiązek angażować się w życie lokalnych społeczności, prowadzić kluby artystyczne.

Huta angażowała się w życie kulturalne, na przykład prowadząc system stypendialny dla wszystkich, którzy chcieli studiować. I to nie tylko dla przyszłych inżynierów i pracowników huty, ale także dla artystów i humanistów.

Gdzie działały takie kluby? Przy domach kultury?

Nie! Bardziej w osiedlowych świetlicach, w blokach. To nie były jakieś odgórnie organizowane zajęcia, tylko okazja, żeby porozmawiać o sztuce, o konkretnych dziełach, o tym, nad czym kto teraz pracuje. W gruncie rzeczy artyści przyjeżdżali tu jak na program rezydencyjny, tylko na całe życie.

Sercem miasta była jednak nie sztuka, a huta.

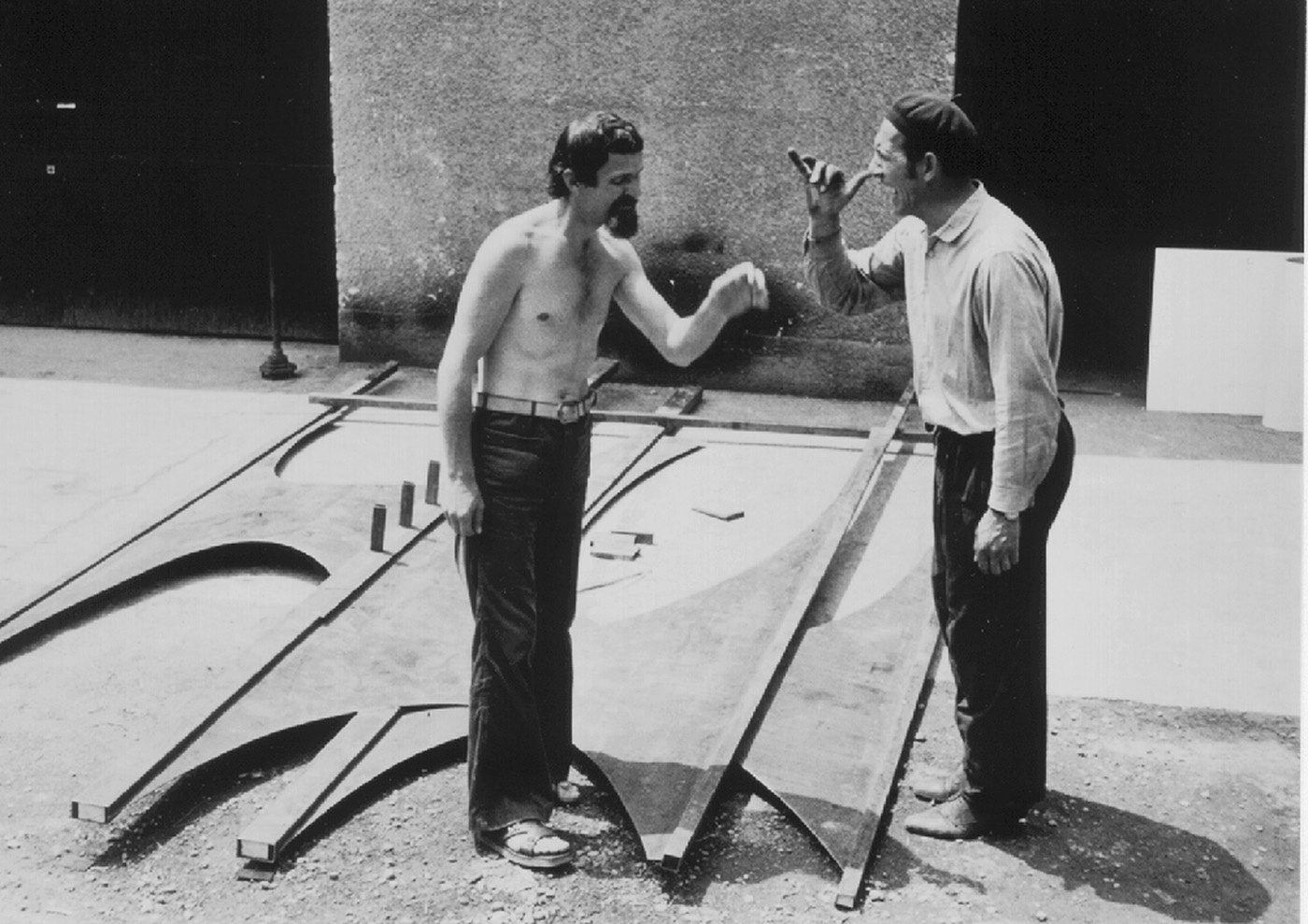

Oczywiście, co nie zmienia faktu, że także huta angażowała się w życie kulturalne, na przykład prowadząc system stypendialny dla wszystkich, którzy chcieli studiować. I to nie tylko dla przyszłych inżynierów i pracowników huty, ale także dla artystów i humanistów. Historia Parku Rzeźby, jak niemal wszystko w Dunaújváros, jest także związana z hutą. Istvan Birkas, artysta i inżynier, który tam pracował, wpadł na pomysł, żeby wykorzystać świetne zaplecze technologiczne, którym dysponowało miasto i zaprosić tu na warsztaty rzeźbiarzy. Pierwszy warsztat, zorganizowany w 1974 roku, obywał się jeszcze na lokalnej uczelni, chociaż surowce oczywiście pochodziły z huty. Rok później, w 1975, zaproszeni artyści przenieśli się do huty, gdzie w obróbce metalu pomagali im robotnicy, wtedy też postanowiono nadać temu przedsięwzięciu cykliczną formę. Sam pomysł zresztą wziął się z Elbląga, gdzie fabryka organizowała Biennale Form Przestrzennych – ostatnia edycja w Polsce odbyła się rok przed rozpoczęciem węgierskich warsztatów.

Biennale rzeźby w Dunaújváros, 1975

Jak wyglądały te warsztaty? Kto mógł się starać o przyjazd do modelowego, socjalistycznego miasta?

W pierwszych latach biennale przyjeżdżali tu zaproszeni artyści, wybierani przez komitet. Od 1977 można było się zgłaszać z projektami, a jury ze Stowarzyszenia Młodych Artystów wybierało najciekawsze plany. Od 1983 roku impreza miała charakter międzynarodowy, więc dziś w Dunaújváros mamy rzeźby szkockich czy amerykańskich artystów. Co dwa lata na kilka tygodni przyjeżdżali tu na kilka tygodni artyści, którym zapewniano diety, wyżywienie i nocleg, jak to w trakcie rezydencji. Wszyscy zakwalifikowani do udziału mogli korzystać z materiałów, zapewnianych przez hutę, gdzie w trakcie pobytu pracowali. Każdy uczestnik dostawał też do pomocy całą brygadę. Bywały zresztą sytuacje zabawne – te brygady, jak to w socjalistycznych krajach, nosiły imiona – Lenina, Stalina, Jurija Gagarina. Jedna z nich, po pracy z György Galántai’em, wniosła o zmianę nazwy brygady – chcieli stać się brygadą Györgyego Galántaia!

Prośba została wysłuchana?

Niestety nie. Galántai, założyciel Artpool research centre w Budapeszcie, był na cenzurowanym. Na Węgrzech artyści byli podzieleni na trzy kategorie: pierwsi otrzymywali hojne wsparcie od państwa, drudzy nie, trzeci nie mieli nawet możliwości wystawiania. On należał do tej ostatniej grupy, nie mógł się starać o żadne stypendia, dotacje. Ale mimo tego udało mu się tu przyjechać aż sześć razy, więcej niż komukolwiek innemu.

Jak to się stało?

Chyba trochę zgodnie z założeniem, że najciemniej jest pod latarnią: właśnie tu, w modelowym mieście, można sobie było na trochę więcej pozwolić. A z drugiej strony, nie czarujmy się, to nadal były peryferia, a nie Budapeszt. Dziś dojazd trwa godzinę, ale wtedy było znacznie dłuższy i trudniejszy. No a prace jednak miały tu zostać, więc Stowarzyszenie Młodych Artystów mogło wybierać projekty kierując się jakością, a nie polityką.

Biennale rzeźby w Dunaújváros, 1981

Czyli ta peryferyjna sytuacja w gruncie rzeczy służyła wszystkim.

Fabryka była, owszem, państwowa, ale pewne zasady dało się tu omijać. To była jedna z tych szczelin, gdzie nie wszystkie zasady egzekwowano surowo. I zresztą na długo tak tu pozostało – nawet po 1989 roku niewiele się zmieniło. Do 2000, kiedy huta została sprywatyzowana i sprzedana firmie z Ukrainy, wiele rzeczy działało tu jak dawniej – system stypendialny i biennale też. Właśnie dlatego, mimo nieco większych problemów, biennale udawało się organizować aż do końca XX wieku. W latach dziewięćdziesiątych odbyło się tylko w 1993, 1996 i w 2000 roku, ale przetrwało transformację. Kiedy huta została sprywatyzowana, finansowanie cofnęła także gmina.

Nie wszyscy mieszkańcy znają ich historię i rozumieją, skąd one się tutaj wzięły. Ale te rzeźby mocno funkcjonują w zbiorowej świadomości – nastolatki lubią tu przychodzić, robią tu imprezy, fotografują się.

Czy od początku rzeźby w ramach biennale tworzono z myślą o Parku Rzeźby?

Absolutnie nie! To, jak wiele innych rzeczy, udało się przypadkiem. Obiekty stworzone w trakcie warsztatów, przechowywano w magazynie. Kiedy miasto odwiedzał jakiś wysoko ustawiony urzędnik państwowy, chciano się przez nim pochwalić i przewieziono je nad brzeg Dunaju, gdzie stoją (choć w nieco innym układzie) aż do dziś.

Od czasów Tibora Weinera i jego modernistycznych zapędów minęło już wtedy ponad trzydzieści lat – czy mieszkańcom podobały się te abstrakcyjne, stalowe rzeźby?

Nie, kompletnie. Ani mieszkańcy, ani lokalni politycy nie byli początkowo zachwyceni. Żyli raczej wśród socrealistycznych projektów, nie interesowała ich awangarda. Z drugiej strony, sporo z nich pracowało w hucie, a część była bezpośrednio zaangażowana w produkcję niektórych prac – ci od początku byli nastawieni entuzjastycznie, to był dla nich powód do dumy. Dziś zdania się podzielone – niektórzy ich nie lubią, bo życzyliby sobie wymazać z historii miasta socjalizm, jakby nie rozumiejąc, że to naprawdę niemożliwe. Nie wszyscy mieszkańcy znają ich historię i rozumieją, skąd one się tutaj wzięły. Ale te rzeźby mocno funkcjonują w zbiorowej świadomości – nastolatki lubią tu przychodzić, robią tu imprezy, fotografują się. Niektóre, najbardziej charakterystyczne, funkcjonują pod różnymi ksywami, często innymi w różnych pokoleniach.

Nie da się jednak ukryć, że stalowe rzeźby nie wyglądają dziś jak nowe: miejscami rdzewieją, przydałaby się im renowacja.

Dlatego, w fundacji Dunaferr-Art staramy się odnowić zarówno rzeźby, jak i samą tradycję. Pierwsze powinno się stać możliwe w przyszłym roku – zabiegamy o to od pewnego czasu, ale ponieważ rzeźby podlegają ochronie przez Ministerstwo Zasobów Ludzkich, zabiegamy o rozpoczęcie procedur od kilku lat. Druga sprawa to biennale: już w połowie listopada w Dunaújváros odbędzie się, po piętnastu latach przerwy, kolejna edycja. Tym razem na nieco mniejszą skalę, ale udało nam się pozyskać środki i zaprosić do współpracy trójkę młodych artystów – Pétera Szalaya, Kitti Gosztolę i Tamása Kaszása – znów w wyborze pomagało nam Stowarzyszenie Młodych Artystów. Po raz kolejny także udało nam się namówić do udziału hutę, i choć czasy przydziałów darmowej stali dla artystów minęły bezpowrotnie, jesteśmy zachwyceni, że historia zatoczy koło.

Biennale rzeźby w Dunaújváros, 1975

ENG

Martyna Nowicka: Why, in a small city on the Danube, do we find a riverbank park

full of steel abstract sculptures?

Annamaria Nagy: Those sculptures have close ties with both the history of this place and the biennale which used to be held here over almost thirty years. At first, their presence may seem surprising, especially if we enter the park having walked through the socialist realist part of Dunaújváros, but in fact their origin can be traced back to the very same socialist guidelines as in the case of this entire city.

Everything here started with the idea that Hungary needed a steelworks. Before the Second World War it was predominantly a rural country: it had favourable climate and fertile soils, so crops had been good here for ages. After 1945, however, a decision was made to turn the People’s Republic of Hungary into a coal and steel tycoon. Trouble was we barely had any deposits of those resources. According to the original vision, the steelworks itself and the perfect city surrounding it, the capital of metallurgy, were supposed to be located much closer to the Yugoslavian border. Due to strategic reasons, they were eventually established here, right in the middle of the country. Resources were meant to be transported over from the mountains down the Danube, but that idea soon proved rather dubious. The water level in the river was almost always either too high or to low, and the current too brisk or too slow. All in all, the plans only looked good on paper.

There were attempts to encourage artists to move to Dunaújváros. Painters and sculptors would be given flats and workshops here apart from being offered regular salaries. In return they created for the city and were obligated to engage in community life, e.g. through running art clubs.

Not all of Dunaújváros looks socialist realist. There are more locations which, like the sculpture park, come from a different aesthetic reality.

That is true. The first architect who took charge of urban planning and construction around here was Tibor Weiner. He had been trained in the Bauhaus, worked in the USSR,

in Basel, and in Paris; spent the war years in Chile, and only came back lured by

a chance to build a new city from scratch. The first designs here were truly modernist, but the communist party soon gave up on those aesthetics. Modernism was not compatible with Stalin’s idea of a city. What they did not give up on was their approach towards the people who would live here. From the very beginning it was a wealthy place: a model for all the other socialist towns and cities. Even though it was originally meant to only have 20 thousand inhabitants, those people were given not just hospitals and canteens, but also cultural community centres, a cinema and a theatre. Next to the plant, a city began to grow: one that was supposed to be a model, and whose inhabitants would live perfect socialist lives.

Does that mean culture was always meant to be important here? Which artistic discipline was most emphasised?

From the start, the authorities focused on high culture. That was why not only works of art were brought over and cultural infrastructure was built, but there were also attempts

to encourage artists to move to Dunaújváros. Painters and sculptors would be given flats and workshops here apart from being offered regular salaries. In return they created for the city and were obligated to engage in community life, e.g. through running art clubs.

The plant was also engaged in cultural life, for example, via its scholarship system that anyone who wanted to study could benefit from. And by ”studying” I do not just mean studying engineering: the program applied to artists and humanists too.

Where would such clubs operate? At the community centres?

No! In most cases in neighbourhood after-school rooms, in the very blocks of flats. Those were not top-down ordered obligatory classes, but an opportunity to talk about art and specific works, also the things particular artists were working on at that moment. The artists would come here for something similar to a residency, but their stay would last their whole life.

Still, at the very heart of the city was the steelworks, not art.

Of course, but that does not alter the fact that the plant was also engaged in cultural life, for example, via its scholarship system that anyone who wanted to study could benefit from. And by ”studying” I do not just mean studying engineering: the program applied to artists and humanists too. Also the origin story of the sculpture park is, just like almost anything in Dunaújváros, connected to the steelworks. Istvan Birkas, artist and engineer who used to work at the plant, came up with an idea to take advantage of the city’s great technological assets and invite sculptors over for a workshop. The first workshop took place in 1974. It was then held at the local collage, but the supplies obviously came from the steelworks. A year later, in 1975, the invited artists would move to the very plant, where regular workers would help them in working the metal. That year a decision was made to make the event cyclic. By the way, the very idea was born in Elbląg [Poland] where the local plant organised the Biennale of Spatial Forms. Its last edition took place one year before the first workshop in Hungary.

Dunaújváros sculpture biennial, 1975

What were those workshops like? Who could apply for a stay in this model socialist city?

In the first years of the biennale, it would be attended by committee-selected artists.

As of 1977 you could submit your project, and the jury consisting of members of the Young Artists Association would choose the most interesting designs. Since 1983 the event has had international character, so today we also have works of Scottish or American sculptors in Dunaújváros. Every two years, selected artists would come and spend several weeks here. They were given per diems, accommodation and boarding, just like artistic residents. All those who were accepted could use the material provided by the steelworks, in which they worked during their stay. Every participant was also assigned their own crew. Sometimes, there were funny situations, since those crews, as was customary in socialist countries, were named after Lenin, Stalin, Gagarin, etc. One crew, having worked with György Galántai, applied for their name to be changed in his honour.

Was their request granted?

Regrettably, no. Galántai, founder of the Budapest Artpool research centre, was frowned upon. In Hungary, artists were divided into three categories: those who were generously subsidised by the state, those who were not, and those were even deprived of chances to exhibit their work. He was a member of the latter group, and therefore could not apply for any scholarships or donations. Still, he was able to come here six times, which is more than anyone else.

How did that happen?

It is like in the proverb: you can’t see the wood for the trees. And so, here, in this model city, a little more then elsewhere could be tolerated. On the other hand, let us not fool ourselves: we are still in the peripheries, not in Budapest. It now takes an hour to get here, but back then the trip was much longer and less comfortable. Also, the artists’ works would stay in Dunaújváros, so the Young Artists Association could pick them based on quality, not policy.

Dunaújváros sculpture biennial, 1975

It seems being in the peripheries was good for everybody.

The steelworks was, of course, state-owned, but certain rules could be omitted. It was

a niche where not all the regulations were strictly enforced. Actually, it stayed that way for long, and even after 1989 little changed. Up until the year 2000, when the steelworks was privatised and sold to a Ukrainian company, the scholarship system and the biennale were kept alive. That way, it was possible to maintain the event until the end of the 1990’s. In that decade it was only held in 1993, 1996 and 2000, but at least it survived the political shift. Once the steelworks got privatised, municipal funding was also withdrawn.

Not all the inhabitants know the story and why the sculptures are even here. But even so, the park is very present in the local collective consciousness: teenagers like to come here, they party and take pictures.

Were the biennale sculptures always created with the Sculpture Park in mind?

Not in the least! It is one of many things which happened by chance. The objects created during the workshops were stored in a warehouse. Once, when some high-rank official visited Dunaújváros, they were displayed on the river bank just so the city could boast of them. And there they are (albeit arranged differently) still today.

Dunaújváros sculpture biennial, 1975

Back then, it had already been three decades since the times of Tibor Weiner and his modernist ambitions. Did the locals like the abstract steel sculptures?

No, not at all. Both the city dwellers and the local politicians were very sceptical at first. They were used to socialist realism designs, and did not care much for avant-garde. On the other hand: many of them worked for the steelworks, some had even been directly involved in the production of the works. The latter were enthusiastic from the very beginning, because they saw the sculptures as something to be proud of. Today, views are divided. Some do not like the sculptures, because they would like socialism as such to be wiped out from the city’s history, as if they really did not understand that was not feasible. Not all the inhabitants know the story and why the sculptures are even here. But even so, the park is very present in the local collective consciousness: teenagers like to come here, they party and take pictures. The most characteristic sculptures even have their nicknames, sometimes several, each used by a different generation.

Still, we cannot not notice that the sculptures do not look like new anymore. In places, there is rust. They could use a renovation.

That is why at the Dunaferr-Art foundation we are trying to renew both the sculptures themselves and the tradition of the event. The first thing should be achieved next year: we’ve been applying for funds for some time now, but since the sculptures are supervised

by the Ministry of Human Capacities the procedures have taken a few years to commence. Another thing is the biennale. Already in mid-November, after a fifteen-year interval, another edition will be held in Dunaújváros. This time the scale will be more modest, but still we managed to secure funding and invite three young artists to collaborate. They are Péter Szalay, Kitti Gosztola and Tamás Kaszás. Once again, the Young Artists Association helped with the selection. We’ve also been able to once again convince the steelworks to take part. The times of free-of-charge steel may be over, but we are still thrilled that history will come full circle.