Konieczność stworzenia ważnej instytucji. Rozmowa z Markiem Pokorným

Karolina Plinta: Jesteśmy teraz galerii Plato. Jest to nowa galeria w Ostrawie, czy możesz coś mi o niej powiedzieć? Interesuje mnie także historia miejsca, w którym znajduje się galeria – jest to zrewitalizowana huta.

Marek Pokorný: Ten teren został otwarty trzy lata temu, ale historia Plato jest dłuższa i zaczyna się na początku lat 90., kiedy artyści, kuratorzy i ludzie ostrawskiego środowiska artystycznego zaczęli starać się o własną instytucję zajmującą się sztuką współczesną. Od tego czasu powstało wiele projektów i ofert powstania czegoś w typie kunsthalle.

Ponieważ nie było nic takiego?

Tego typu instytucji nie było w Ostrawie. Istnieje tu galeria sztuki, ale de facto jest to muzeum, którego kolekcja skupia się na różnych formach artystycznej aktywności i dziedzictwie od XV i XVI wieku do współczesności. Jest to małe, standardowe muzeum sztuki, nieskore do eksperymentowania i nie posiadające przestrzeni przeznaczonych wyłącznie na sztukę współczesną… Jego działalność nie była wystarczająca dla artystycznego środowiska z Ostrawy, szczególnie ze względu na jego wyjątkową historię i pozycję na czeskiej scenie.

Jakiego rodzaju wyjątkowość masz na myśli?

Jest to związane ze specyfiką regionu i mentalności jego mieszkańców – jest ona kompletnie inna niż w Brnie czy Pradze. Także tradycje artystyczne są tu całkowicie inne. Artyści z Ostrawy są bardziej nastawieni na performans i bezpośrednie odnoszenie się do życia społecznego.

Dlaczego?

Ponieważ życie tutaj, w Ostrawie, jest naprawdę ciężkie i było takie od samego początku, kiedy miasto powstawało w XIX wieku. Ten region podlegał również bardzo silnej, ideologicznej presji ze strony komunistów w latach 60., 70. i 80. – i to w sposób niezwykle brutalny. Oczywiście, tego rodzaju presja istniała także w innych regionach, ale tutaj była szczególnie silna ze względu na obecność robotników, było to najbardziej przemysłowe miasto w Republice Czeskiej. Z tego względu ten region jest specjalny, ludzie tutaj inaczej się zachowują, wydają się być bardziej nieokrzesani, trudni, ale również romantyczni. Wszystkie te przyczyny wpływają na pozycję tego miejsca, wizerunek lokalnego artysty i jego roli w Ostrawie. Do tego dochodzi poczucie funkcjonowania na peryferiach Czeskiej Republiki, które tutaj było i jest bardzo silne.

W pewien sposób przypomina mi to sytuację Śląska, tyle że jego mieszkańcy postrzegają swój region jako bardzo niezależną część Polski. Są także bardzo dumni z bycia Ślązakami. Mieszkańcom Ostrawy nie towarzyszy podobne uczucie?

Nie, ponieważ w przeszłości jednym z głównych miast Śląska była Opawa. Ostrawa jest bardzo młodym miastem, została zbudowana w drugiej połowie XIX wieku. Powiedzmy, że można je porównać do Łodzi. Mieszkańcy Ostrawy przybyli tu z różnych miejsc, również ze Słowacji i Polski. Opawa tymczasem ma głębsze zaplecze kulturalne i historyczne. Ostrawa jest bardzo specyficznym, nowym miastem industrialnym, bez tożsamości sięgającej XV, XVII czy XVII wieku. Jej znaczącym komponentem jest siła – fizyczna, jak również polityczna – ale również zmęczenie, i jest to tutaj bardzo spolaryzowane, bardziej niż w jakimkolwiek mieście w Czechach. Takie wyobrażenie o sobie mają mieszkańcy Ostrawy, ale jest ono popularne także w innych częściach kraju (śmiech). Powiedzmy, że Ostrawa to czarne serce Czeskiej Republiki. Dla przykładu, mój przyjaciel opublikował tomik poezji o Ostrawie i nazwał go „briketa”, czyli brykiet.

Na podstawie takich obrazów i symboli stworzona jest lokalna tożsamość i właśnie dlatego jest ona szczególna, co przekłada się także na lokalną scenę. Oczywiście, mieszkańcy Ostrawy są dumni ze swojego miasta, ale w specjalny sposób, ponadto potrzebują oni wsparcia i miejsca, gdzie będą mogli prezentować swoje działania, i które będzie dawało im możliwość konfrontacji z czymś, co nie przynależy do lokalnego kontekstu. Idea stworzenia tego rodzaju instytucji była tutaj obecna od wczesnych lat 90., ale polityczny establiszment nie był zainteresowany jej realizacją. Możliwość pojawiła się dopiero trzy lata temu. Właściciel tego terenu – jest to własność prywatna – wpadł na pomysł rekonstrukcji i rewitalizacji kompleksu pustych budynków w celu stworzenia tutaj nowego centrum Ostrawy, ściśle związanego z historią miasta i jego kulturą. Wiązało się to również z możliwością założenia tutaj czegoś w rodzaju kunsthalle.

Kto jest właścicielem tego kompleksu?

Pan Světlík, który zajmuje się przemysłem ciężkim. Na przykład, budynek naprzeciwko Plato ciągle działa jako fabryka. Jak widzisz, tylko część tego terenu jest pusta, w drugiej połowie znajdziesz kilka fabryk, jest to park przemysłowy.

Dlaczego właściwie wpadł on na pomysł wprowadzenia tu kultury? Jest nią jakoś szczególnie zainteresowany?

To długa historia. Na początku chciano cały ten teren poddać recyklingowi, ponieważ jest tu dużo żelaza – chcieli je sprzedać, ale okazało się to niemożliwe, ponieważ teren jest częścią narodowego dziedzictwa kultury. Drugą opcją było wykorzystanie pieniędzy z Unii Europejskiej na odbudowę miejsca i przekształcenie w ośrodek związany z kulturą, edukacją, polityką historyczną itp. Plan ten zakładał też budowę kunsthalle. Jednak ponieważ jest to własność prywatna, a właściciel jest… bardzo interesującą postacią, ale… kasa to kasa (śmiech), więc stanęło na tym, że zawarł on układ z miastem, i to właśnie miasto przygotowało grunt do budowy galerii sztuki współczesnej. To był kluczowy punkt tej sprawy, co przyczyniło się do wielu tarć pomiędzy lokalnym środowiskiem artystycznym, właścicielem i miastem. Artyści, aktywiści i krytycy nie byli zbyt zadowoleni z tego pomysłu.

Dlaczego?

Ponieważ jest to wiąż prywatny budynek i nikt nie wie, co się może stać w przyszłości, w przeciągu dwóch albo trzech lat.

Park przemysłowy w Dolnych Vitkovicach, Ostrawa, w głębi budynek Gongu, gdzie znajduje się galeria Plato

Czyli w takim razie Plato nie jest do końca publiczną galerią?

Przeciwnie, jest. Fundusze, którymi operuje galeria pochodzą z miasta. Do realizacji naszych działań używamy publicznych pieniędzy, ale działamy w tym miejscu. Ten projekt jest więc specyficzną konstrukcją, złożoną z prywatnego właściciela, miasta i regionu. Jest nad nim trochę publicznej kontroli, ale wpływ właściciela może być pod pewnymi względami silniejszy. Projekt rozpoczął się w 2013 roku i było wokół niego wiele dyskusji, których rezultatem jest moja obecność tutaj. Jestem kimś w rodzaju mediatora, osoby spoza lokalnego środowiska, interesów i konfliktów. Mam trochę doświadczenia w pracy nad artystycznymi projektami, może osobą respektowaną przez artystów, kimś kogo każdy zna… I jestem nieprzekupny. Moją misją jest przekształcenie tego projektu, kończącego się w 2016 roku (mamy fundusze na galerię do 2016 roku). Zależmy mi na stworzeniu czegoś w rodzaju organizacji, przy użyciu publicznych pieniędzy, i przygotowania jej do transformacji w normalną instytucję. Oznacza to również przewodniczenie w dyskusjach pomiędzy miastem i artystami i przygotowywanie się do drugiej części projektu po 2016 roku.

To znaczące, że cały czas mówisz o Plato jako projekcie, a nie instytucji.

Nie jest to instytucja na ten moment, pracujemy jak instytucja, ale jesteśmy projektem. Nie chcielibyśmy zostawiać tu w przyszłości. Wolałbym opuścić to miejsce i założyć instytucję, lub coś jak platformę w różnych lokalizacjach w mieście. Oficjalna nazwa całego projektu brzmi „Galeria Miasta Ostrawy”, ale ja, jako lider projektu, skonstruowałem swój własny program, który nazwałem „Plato – Platforma (Sztuki Współczesnej) Ostrawa”, ponieważ nie wiem czy koniecznością jest posiadanie jednego miejsca lub budynku – dlaczego powinniśmy pracować tylko w jednej przestrzeni? Nie jestem również pewny, czy ta przestrzeń jest dobra na przyszłość. Tak więc Plato w moim wyobrażeniu jest strukturą horyzontalną, odnoszącą się w różny sposób do miasta, charakteryzująca się różnego typu działaniami w swojej praktyce – to jest właśnie preferowana przeze mnie wizja. Podobna mi się również otwartość tej propozycji, która jest także otwartością na przekształcenie w coś w rodzaju instytucji, choć wolałbym zachować ją jako platformę.

Zacząłeś rozglądać się za innymi miejscami w Ostrawie, w których można by w przyszłości pracować?

Tak, i właśnie dyskutujemy o tym z miastem. Moja wizja zyskała ogólne poparcie, ponieważ pojawili się nowi włodarze miasta i sytuacja się zmieniła. Pierwszym krokiem ku zmianom było zdobycie tego „TAK”, co dobrze rokuje na przyszłość, a drugi to jakiś pomysł.

Nowi włodarze są bardzo otwarci.

Hm, wiesz, jesteśmy dopiero na początku, nikt nie wie co się stanie dalej. Ale włodarze wiedzą, że obecna lokalizacja Plato nie powinna być docelowym miejscem dla tego rodzaju projektu i teraz możemy zacząć pracować nad kwestią, co powinno stać się po 2016 roku. Jeśli to się uda, będę szczęśliwy, bo to jest właśnie moja misja.

Co zrobiliście w Plato w ciągu tego roku? Pracowaliście z dość specyficznym nastawieniem, wiedząc, że ten budynek jest tylko tymczasowym miejscem.

Tak, ale używamy go w standardowy sposób, robimy wystawy i projekty; na przykład, zrobiliśmy projekt poza tym terenem, przy którym współpracowaliśmy z miejską biblioteką. Jest to normalna galeria w tym momencie.

Jak wygląda program artystyczny Plato? Na jakiego rodzaju sztuce jesteście tutaj skoncentrowani?

Ciężko jednoznacznie to zdefiniować. Z mojego punktu widzenia, bardzo istotne jest wprowadzenie do Ostrawy głosów z zewnątrz – co odnosi się do specyficznej mentalności mieszkańców Ostrawy i orientacji sceny artystycznej, o której już mówiliśmy. Ponadto, istotne jest dla mnie to, żeby wnieść do tej instytucji profesjonalizm, przez który uważam tworzenie projektów w standardowej formule – produkcji, dramaturgii, programu, katalogów, zarządzanie projektem. Kolejna rzecz to profesjonalne zaplecze – prezentacja w Ostrawie twórczości innego typu. Może bardziej konceptualnej, albo… post-konceptualnej (śmiech).

Tutaj w Ostrawie artyści nie są tak zaznajomieni ze sztuką konceptualną i post-konceptualną?

Na swój sposób jest ona tu obecna, ale głównie sztuka jest zorientowana na performansie, malarstwie i akcji. Fotografia, nowe media i sztuka konceptualna w ścisłym znaczeniu tego słowa tutaj nie istnieją. Tutejsi artyści preferują na przykład figurację. Oczywiście, dla mnie to jest sytuacja interesująca, jest w tym wiele autentyczności, ale pewnie przydałoby się im więcej konfrontacji z czymś, co jest inne.

Kdo na moje místo, widok na wystawę, kur. Marek Pokorný, Zbyněk Baladrán, 2015, Plato, Ostrawa, fot. Tomáš Souček

Czy możesz powiedzieć mi coś o wystawach, jakie miały już miejsce w Plato?

Jest to poniekąd trudne, ponieważ dwie pierwsze wystawy nie były kuratorowane przeze mnie, to nie był mój pomysł – ja zostałem powołany na to stanowisko pod koniec 2013 roku. Musiałem szybko zacząć działać, bez przygotowania. Mój pierwszy projekt to wystawa Jana Šerýcha, który jest dobrze znanym artystą w średnim wieku z Pragi, konceptualistą i malarzem, dążącym do transformacji języka w koncepty wizualne. Później przygotowałem wystawę Michała Kalhousa, który jest fotografem i mieszka w Ostrawie, ale nie jest tu bardzo znany, ponieważ jak do tej pory nie miał on tu żadnej dużej wystawy. Jego pierwsza solowa wystawa w Ostrawie dotyczyła jego życia rodzinnego. Praca z artystami z Ostrawy jest dla mnie bardzo ważna, ale chcę, żeby była ona inaczej wyakcentowana. Tak było na przykład w wypadku niedawnej wystawy o Peterze Bezruču, poecie powiązanym blisko z Ostrawą. Wszyscy go tu znają i nadal wielu go czyta. Powiedzmy, że jest on jednym z kluczowych odniesień dla ostrawskiej kultury, ale nasza interpretacja jego twórczości jest zupełnie inna od dominującej w Ostrawie. Kolejnym projektem była wystawa Iriny Koriny, rosyjskiej artystki, której twórczość uwielbiam od wielu lat. Jej wyobraźnia i dorobek wydają się być blisko ostrawskiej mentalności, ale pracuje ona w zupełnie inny sposób, kładzie większy nacisk na estetykę. Chciałbym tu zaoferować coś, co jest znajome, ale dziwne, bliskie lokalnej mentalności ale w pewien sposób dalekie, lub coś co jest całkowicie różne od obecnego stanu ostrawskiej sztuki. Innym przykładem jest Vladimír Houdek, który zdobył Jindřich Chalupecký Prize dwa lata temu – on jest malarzem, ale robi inne rzeczy niż możesz zobaczyć tu w Ostrawie lub w departamencie sztuki na lokalnym uniwersytecie.

Jakie jest znaczenie w tym zestawie wystawy Kateřiny Vincourovej, która niedawno miała miejsce w galerii?

Jej wystawa w Plato jest kolejną częścią mojej koncepcji. Chciałbym połączyć sztuki wizualne z innymi obszarami produkcji kulturalnej. Ponadto, muzyka jest istotną częścią działań w miejskim programie publicznym. W tym rejonie odbywa się jeden bardzo istotny festiwal muzyczny, biennale muzyki nowej i eksperymentalnej Ostrava Days, co jest dla nas ważnym kontekstem. Festiwal został założony przez Petera Kotíka, muzyka i kompozytora, mieszkającego w Nowym Jorku od końca lat 60. W tym roku Plato będzie współpracować z biennale, pokażemy tam instalację Alvina Luciera i Karla-Heinza Stockausena, planujemy również projekcję dokumentów Virginii Dwan, (prominentnej nowojorskiej galerzystki działającej na przełomie lat 60. i 70.), które są dedykowane Johnowi Cage’owi i Robertowi Smithsonowi. Performans, oraz zagadnienia literackie i teatralne w sztuce to kolejne kluczowe tematy które eksplorujemy, poprzez inscenizowane czytania oraz konfrontację tekstu z sytuacją galeryjną. Obecnie przygotowujemy także festiwal teatralny, wykorzystujący środki zazwyczaj związane z plastyką; na przykład, chcemy wystawić Mszę Artura Żmijewskiego w Ostrawie. Wokół Plato zawsze kręci się grupka pisarzy, muzyków i performerów, co także jest charakterystyczne dla Ostrawy, a my podkreślamy ten aspekt naszej działalności lub przesuwamy ją w kierunku innych form sztuki. Program dla publiczności tylko częściowo jest połączony z wystawienniczym, dla nas jest to misja paralelna: jej celem jest pośredniczenie w odbiorze sztuki współczesnej, ujmowanej w relacji do całości kulturalnej produkcji, oraz poszukiwanie wspólnego mianownika i interesów różnych dyscyplin artystycznych.

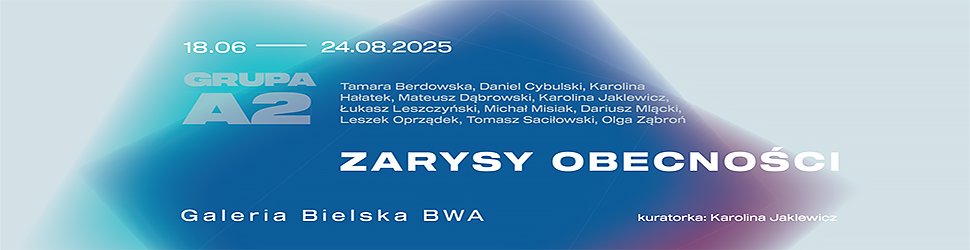

Kateřina Vincourová, Nahlížet nasloucháním/ Listening Eyes, 2015, Plato, Ostrawa, fot. Martin Popelář

Co będzie się działo w Plato w najbliższych miesiącach?

Jednym z projektów, który obecnie ma miejsce jest The Exhibition Lindy Dostálkovej, scenografki, graficzki i artystki, powstały we współpracy między innymi z Norą Turato, Nicholasem Riis i czeską grupą Rafani. The Exhibition jest efektem dyskusji o skostnieniu formuł wystaw sztuki współczesnej. To studium przypadku galeryjnej sytuacji oraz relacji pomiędzy wystawą i dziełem sztuki. Obiekt Kateřiny Vincourovej został zastąpiony instalacją dźwiękową, Fuck, autorstwa Václava Stratila, enfant terrible czeskiej sztuki, oraz jego studenta, który sam siebie nazywa Panáčik. Na sezon letni przygotowujemy Autonomy, pierwszą tak obszerną retrospektywę Václava Magida, artysty podpisującego się pod radykalnym, lewicowym dyskursem i jego ambiwalentnymi wymaganiami, oraz instalację Stano Filko, wiodącego bohatera słowackiej neoawangardy. Tak się złożyło, że jego prace będzie można zobaczyć także w warszawskiej Zachęcie miesiąc później. Rok zamkniemy wspólną wystawą Michała Budnego i Jaromíra Novotnego. W szerszej perspektywie, rozważam organizację wystaw Pavla Pepperštejna i Toma Sachsa, jesteśmy teraz na etapie negocjacji z Maix Mayerem, a do tego oczywiście dochodzą wystawy czeskich artystów, takich jak Vladimír Skrepl, mniej znana, ale znakomita Markéta Vaňková i rzeźbiarka Šárka Mikesková – kluczowa postać ostrawskiej sceny. Naturalnie, jesteśmy także bardzo zainteresowani tym, co się dzieje w Polsce. To mniej więcej tyle.

Moje ostatnie pytanie odnosi się bezpośrednio do ciebie, Marek. Jak wiem, przed przenosinami do Plato byłeś dyrektorem Morawskiej Galerii w Brnie, wziąłeś także udział w konkursie na pozycję dyrektora artystycznego Galerii Narodowej w Pradze. Nie wygrałeś go, ale zacząłeś pracować jako dyrektor Plato. Co znaczy dla ciebie, po pracy w tak dużej i znaczącej galerii, ta przeprowadzka do Ostrawy?

Dla mnie oznacza to konieczność stworzenia ważnej instytucji w Ostrawie (śmiech). Ale na serio: moje zainteresowania koncentrują się wokół instytucji jako ramy dla dystrybucji, oceny i produkcji sztuki, więc możliwość eksperymentowania z formatami organizacji i kierowanie nowymi projektami jest dla mnie bardzo motywująca. Dodatkowo, w Ostrawie mam szansę powrócić, po wielu latach, do bezpośredniej współpracy pomiędzy artystami i kuratorami – do tego w nowej sytuacji, kiedy wyraźnie dostrzegalna jest zmiana w autorefleksji sceny artystycznej oraz w oczekiwaniach artystów i kuratorów, a także w momencie, kiedy, w mojej opinii, zmieniają się funkcje tego, co określamy jako sztukę współczesną. Kiedy prowadzisz jedno z głównych muzeów w tym kraju, nie ma zbyt wiele czasu na takie rzeczy. Jeśli jesteś szczęściarzem, może uda ci się przeczytać o tych procesach w publikacjach wydanych przez Hansa Beltinga, Petera Osborne’a i tym podobnych.

Karolina Plinta: We are sitting now in Plato gallery. It’s a new gallery in Ostrava, can you tell me something more about it? I’m interested also in the history of the place, where the gallery is located – it’s in a restored ironworks.

Marek Pokorný: This district was opened three years ago, but behind Plato there is a long history – from the beginning of the nineties. Artists, curators and people from the art scene in Ostrava wished for long time to have their own institution for contemporary art. There were a lot of projects, offers and dreams for something such as a Kunsthalle.

Because there wasn’t any?

There wasn’t any institution of that kind in Ostrava. There exists gallery for art, but in fact this is an art museum, with collections focused on different kinds of art activities and an art legacy from the XV and XVI century up to contemporary art. This is a small standard art museum, without experimentation or spaces dedicated directly to contemporary art… But it was not enough for artists from Ostrava with a specific history and position inside the Czech art scene…

What kind of specificity?

It’s connected with the specificity of the region, and the mentality – it’s absolutely different from Brno, Prague, and the artistic traditions are absolutely different. Artists from Ostrava are more oriented to performance, and with more direct contact with social life.

Why?

Because life here, in Ostrava, is really hard, and it was hard from the beginning, in the XIX century. This region was also under heavy pressure from communist ideology during the 60s, 70s and 80s, in a most brutal way. Of course, this pressure was also in different districts, but here it was especially high, because here were more workers, it was the most industrial city in the Czech Republic. So this region is very special, people behave in a different way, they are more rudimentary, maybe more romantic, but also hard. And all these reasons shaped one’s position to the place, the image of an artist and what it means to be an artist in Ostrava. And also the feeling of being in a periphery of the Czech Republic was very strong here, and still is.

It reminds me in some way of the situation in Śląsk, but people from Śląsk think about their region as a very independent part of Poland. They are very proud of being Silesian. Inhabitants of Ostrava do not have the same feeling?

No, because in the past the main city for Silesia was Opava. Ostrava is a really young city, it was built only in the second half of the nineteenth century. It was something like Łódź. People living in Ostrava came from different places, also from Slovakia and Poland. Opava, in opposition, has a deeper cultural and historic background. Ostrava is a very specific, new, industrial city without its own identity going back to the XV, XVII or XVIII century. A component of its identity is power – wealth, the party – but also tiredness, it’s very polarized here, more than any city of the Czech Republic. It’s the image that the inhabitants of Ostrava have, but it’s also popular in other parts of the country (laughs). Let’s say that Ostrava is the black heart of the Czech Republic. For example, my friend published a book of poems connected to Ostrava, and it’s called “briketa”, that you can translate as a piece of coal. So this is a kind of self-representation, through these images or symbols. That’s why identification here is very special, and this means also the art system. They are proud of Ostrava, of course, but in a special way, and they need some support and a place for the presentation of their own activites, one that will be also a place for confrontation with things that do not belong to the Ostravian context. This idea, of having this kind of institution, was present here since the early 90’s, but the political establishment was not interested in the realization of this idea. Only three years ago, there was a possibility to do it. The owner of this district – it’s private property of course – got this plan to reconstruct or revitalise this complex of empty buildings to found a new centre for Ostrava connected to the history of city and its culture. One of these possibilities was to establish here something like a Kunsthalle.

Who is the owner and what does he do?

Mr. Světlík, he is engaged in heavy machinery. For example, this building opposite Plato is still full of heavy industry. So as you see, only a part of the area is empty, in the second part you will find some factories, there is an industrial park.

And why did he get this idea to bring culture here? He is interested in culture?

It’s long story. In the beginning, they hoped to make money from recycling, because there is a lot of iron – they wanted to sell it somewhere, but it was impossible because this was part of the cultural inheritance of the Czech Republic. The next option was to use money from the European Union to rebuild it with something connected with culture, education, historical memory, etc. One part of this plan was to establish here something like a Kunsthalle. But, because this is private property, and the owner is… a very interesting man, but… money is money… (laughs), so they made a deal with the city, and the city prepared the ground to build their gallery for contemporary art. It was the crucial point and there were big battles between the art scene, the owner, and the city. Artist, activists and critics was not very happy, to do it this way.

Why?

Because it’s still a private building, nobody knows what might happen in the future, within two or three years.

So Plato isn’t exactly a public gallery?

No, it is. The funds which operate the gallery come from the city. We use public money for our activities, but we work in this place. Because this project is covered by a specific construction where there is a private owner, the city, and the region. There is some public control over it, but the influence of the private owner could be in some ways stronger. They launched this project in 2013, and there was a lot of discussion about it, if this was ok or not, and the result of this discussion is that I’m here. I’m something like a mediator, a person outside the local art community, local interests and local conflicts. I have some experience with art projects, maybe respected by the artists, a person who everybody knows… And I’m not corruptible. My own mission is to translate, or transform this project, which is ending in 2016 (we have money for the gallery until 2016). My mission is to establish something like an organization, using for it public money and preparing it for transformation to a standard institution. It also means leading discussions between artists and the city; thinking about the second part of this project after 2016.

Kdo na moje místo, widok na wystawę, kur. Marek Pokorný, Zbyněk Baladrán, 2015, Plato, Ostrawa, fot. Tomáš Souček

It is significant that all the time you are talking about the project, and not an institution.

It’s not an institution at the moment. We are working as an institution, but we are a project. We don’t wish to stay here in the future. I’d prefer to leave this place and establish an institution, or something like a platform in different places in the city. Because the official name of the whole project is “Gallery of the City of Ostrava”, but I, as a leader of the project, I’ve got my own program or project, that is called “Plato – Platform (of Contemporary Art) Ostrava”, because I’m not sure if it is necessary to have one space, or something like “significant building” – why we should work only in one space? I’m also not sure if this space here is the right space for the future of the gallery. So Plato in my mind is a horizontal structure, with different connections in the city, and that also uses different activities in its practice – it’s something that I prefer; and this openness, its openness to the future transformation into something like institution, but I prefer to keep it as a platform in some way.

Have you started to look after places in Ostrava that can be places to work in the future?

Yes, now we are discussing it with the city. I have general agreement with my vision, because there are new representatives of the city, so the situation has changed, and the first step was to have “YES”, this is something good for the future, and the second is some concept.

They are very open.

Hm, you know, we are at the beginning, nobody knows what will happen next. But representatives know that the contemporary location of Plato is not a final space for such a project, and now we can start to work with the problem of what should happen after 2016. If this will be ok, I am happy and that’s my mission here.

What did you do in Plato during the last year? You work with a special kind of idea, that this building is only a temporary place for the gallery.

Yes, but we use it in standard way, we make exhibitions and projects; for example, we made a project outside this district, in which we cooperated with the city library. It’s a standard gallery at the moment.

How does the artistic program in Plato look? On which kind of art are you focused here?

It’s very hard to say. From my point of view, it’s very important to bring to Ostrava some other voices – we have talked about the specific mentality in Ostrava and the orientation of the art scene here; What is important from my point of view is to bring, firstly, professionalism, by which I mean making the project with a standard structure – production, dramaturgy, program, catalogues, management of the project, and the second is professional background – to bring to Ostrava other, different, voices of artistic production. Maybe more conceptual and… post-conceptual (laughs).

Here in Ostrava are artists not so familiar with conceptual, or post-conceptual art?

MP: It’s some how present, but mainly it’s oriented to performance, painting and to action. Photography, new media and conceptual art don’t exist in the strict sense. Artists here prefer, for example, figuration. Of course, I like this situation, because it’s very authentic, but they need more confrontation with something that is different.

Can you say something more about exhibitions which have already taken place in Plato?

MP: It’s somehow hard, because the first two shows were not curated by me, it was not my concept, because I was appointed to the position at the end of 2013. I had to start quickly, but without preparation. My first project here was Jan Šerých, who is well known, a middle-aged artist from Prague, working with the conceptual and painting, he is trying to transform language to visual concepts. Then I prepared an exhibition of Michal Kalhous, who is a part of the Otravian art scene and a photographer, but nobody here knows about him, because he hasn’t had any big exhibition here yet. His first big exhibition in Ostrava was connected with his family life. For me it was very important to work with artists from Ostrava, but in different accents. The exhibition which is going on in the gallery now is about Peter Bezruč, who was a poet connected directly to Ostrava; everybody knows him here and he still has a lot of readers here in Ostrava. Lets say, that he is a referential point to the culture of Ostrava, but our reading of Peter Bezruč is absolutely different than the discussion about Bezruč here. Another project was Irina Korina, she is a Russian artist and I have admired her work for many years; her imagination and work is somewhere near an Ostravian mentality; but she works with it in an absolutely different way, more aesthetically. I wish to offer something which is familiar, but strange, and what is near to the mentality but is somehow far, or something that is absolutely different than the present state of Ostravian art. Another example is Vladimír Houdek, he won a Jindřich Chalupecký Prize two years ago – he is a painter but he does different stuff than you can see here in Ostrava or in the department of art at the University.

What is the significance of the exhibition of Kateřina Vincourova in this collection?

Her exhibition in Plato is another part of my thinking about this project. I want to connect the visual arts with other fields of cultural production. Music is an important part of activities in a public program. In this district we have one very important music festival, Biennial Ostrava Days, and it is also an important context for us. It was established by Peter Kotík, a musician and composer living since the end of the 1960s in New York. This year, Plato will contribute to the Biennial with an installation of Alvin Lucier and Karl-Heinz Stockausen, as well as a projection of documentaries by Virginia Dwan, a prominent New York gallery owner from the late 1960s and early 1970s, dedicated to John Cage and Robert Smithson. The performance, theatrical and literary context of contemporary art is another focal point that we explore, through staged readings and confrontations of texts and gallery situations. We are actually preparing a festival of theatre employing the means usually associated with visual art; for example, we want to present Artur Żmijewski’s Mass in Ostrava. There are always writers, musicians and performers hanging around Plato, which again is characteristic of Ostrava, and we accentuate this aspect or shift it towards topical art forms. The programme for the public, that is only partially linked to our exhibitions, is entitled Parallel Mission: its objective is to mediate contemporary art in relation to the entirety of cultural production, to seek the common denominators and interests of different art disciplines.

What will happen in Plato in the coming months?

One project that is currently taking place is The Exhibition prepared by Linda Dostálková, a stage and graphic designer and artist, in collaboration with Nora Turato, Nicholas Riis, the Rafani Czech art group and others. The Exhibition is the product of discussions of how the forms of contemporary art exhibitions get fossilized. It is a case study of a gallery situation and the relationship between display and a work of art. Kateřina Vincourová’s object has been replaced by the sound installation, Fuck, created by Václav Stratil, enfant terrible of Czech art, and his student who calls himself Panáčik. For the summer season, we are preparing Autonomy, the first-ever extensive retrospective of Václav Magid, an artist subscribing to a radical left-wing discourse and its ambivalent requirements, as well as an installation by Stano Filko, a leading protagonist of the Slovak neo-avant-garde; actually, his work will be displayed in the Zachęta gallery in Warsaw only a month later. The year will close with a joint exhibition of Michal Budný and Jaromír Novotný. In a broader perspective, I’m considering exhibitions of Pavel Pepperštejn and Tom Sachs, we are negotiating a project by Maix Mayer and, of course, exhibitions of Czech artists such as Vladimír Skrepl, the lesser-known but brilliant Markéta Vaňková and sculptor Šárka Mikesková, a key figure of the Ostrava art scene. Naturally, we are also very much interested in what’s happening in Poland. That’s about it.

My last question is directly focused on you, Marek. As I know, before moving to Plato you were director in the Moravian Gallery in Brno, then you took part in the contest for the position of director of the National Gallery in Prague. You didn’t win it, but you started as director of Plato. What does it mean to you, after working in such a big and important gallery, this move to Ostrava?

For me, this means an obligation to establish an important institution in Ostrava. But seriously: what interests me in particular is an institution as a framework for the distribution, evaluation and production of art, so the possibility of experimenting with organisation formats and targeting new projects is a great motivation for me. In addition, in Ostrava I return, after many years, to direct collaboration with artists and curators – in a new situation that has seen a distinct shift in the self-reflection of the art scene and in the expectations and needs of artists and curators, and when, in my opinion, the functions of what we refer to as contemporary art are changing. When you run a major museum in this country, there’s hardly time for any of this, and if you’re lucky, you read about these things in proceedings edited by Hans Belting and books by Peter Osborne and co.

Karolina Plinta – krytyczka sztuki, redaktorka naczelna magazynu „Szum” (razem z Jakubem Banasiakiem). Członkini Międzynarodowego Stowarzyszenia Krytyków Sztuki AICA. Autorka licznych tekstów o sztuce, od 2020 roku prowadzi podcast „Godzina Szumu”. Laureatka Nagrody Krytyki Artystycznej im. Jerzego Stajudy (za magazyn „Szum”, razem z Adamem Mazurem i Jakubem Banasiakiem).

WięcejPrzypisy

Stopka

- Miejsce

- PLATO - Galeria Miasta Ostrawy

- Strona internetowa

- plato-ostrava.cz