Eternal Shapes: Weaving the Erotic into Cybernetics in 1970s Poland

Marie II: That’s what I don’t understand. Why does one say, „I love you”? Do you understand? Why can’t one say, for example, ”Egg”?

Marie I: Well, that’s an idea.

— Věra Chytilová, Sedmikrásky (Daisies), 1966

When boy says to girl, „I love you,” he is using words to convey that which is more convincingly conveyed by his tone of voice and his movements; and the girl, if she has any sense, will pay more attention to those accompanying signs than to the words.

— Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 1972

In the 1960s, Western theorists and activists associated with feminist and decolonial discourses coined the slogan „the personal is political” to question the disconnect between the personal and the power structures in which the individual body is entangled.11 Carol Hanisch, ”The Personal Is Political” (February 1969), originally published in Notes from the Second Year: Women’s Liberation, ed. Shulamith Firestone and Anne Koedt (New York: Radical Feminist Press,1970). The work was widely reprinted and circulated during the Women’s Liberation Movement and afterwards. ↩︎ In the decades that followed, emancipation movements often took corporeal and performative practice as their starting point, with demands for a turn to emotion and personal experience, to the narrative of the private and the political. On the other hand, conservative critics in many countries of Eastern Europe have argued for a very long time that, due to the lack of mass feminist movements, the personal was divorced from the political, or indeed that there had been ”no real feminist art” during the heyday of the 1970s and 1980s avant-garde movements.

To complicate the matter even further, third-wave feminism, which informs the contemporary lens of our current perspective on women artists from Eastern Europe, automatically assigns the embodied condition and sensual imagery of their performances and conceptual art to a ”feminist” paradigm, sometimes against the artists’ own will and right to self-determination. One thinks of artists such as Jolanta Marcolla, Geta Brătescu, and Marina Abramović, to name a few, who despite the presence of what one could call a female gaze in their practice, have nonetheless distanced themselves from the feminist paradigm. But even if they didn’t openly engage with feminist lexicon or agenda, the materialist embodied experience of an artist who simultaneously produces artworks and is involved with feminized labor at home was all too often marginalized. This tension between structural inequality and a desire to become the subject of self-analysis produced work that demonstrated the transformation of the female subject. As writer and curator Karolina Majewska-Güde observed, ”If feminists in the West dealt theoretically with questions of identity and its deconstruction, in the ECE [East Central Europe] this critique was often performed by artists who did not necessarily identify themselves as feminist, but used art to address and examine the issues of language, subjectivity and identity.”22 Karolina Majewska-Güde, Telling Stories about Feminist Art in Socialist Europe. Or the Archive as a Place of Cross-Generational Remaking, ”MIEJSCE” (July 2021), https://www.doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.24501611.MCE.2021.7.2. ↩︎ Analogously, Lina Džuverović, whose thesis on former Yugoslavia could also be applied to other socialist countries, argued that ”women’s roles became more complex, in a negotiation of what has since been theorized by feminist scholars as the division between ’public patriarchy’ (the state) and ’private patriarchy’ (the family).”33 Lina Džuverović, „Feminism Under the Radar: Reading Between the Lines of Token Equality,” dzuverovic.org, https://www.dzuverovic.org/?path=/texts/feminism-under-the-radar readingbetween-the-lines-of-token-equality/. ↩︎ And since the feminist slogan „the private is political” has become the slogan of our most fervent battles waged for the right to self-determination, since there is nothing more intimate and political than one’s own body, the specter of body returns today in the public space, on the post-Communist ruins.

What does it mean to attend the outside world from inside the body? How do feminist artists transpose their bodily experiences into conceptual semiotics? As a woman, I know the experience of my own body as object intimately well, and I am similarly familiar with feelings of depersonalization and derealization—to feel oneself outside of the body is not an uncommon experience for oppressed groups and trauma survivors.

This dichotomy of frameworks opens up several important questions. How does the marked subject make conceptual art in relation to their identity, and what kinds of practices are understood as legitimately critical or rigorous? How must we understand the feminized labor of the artist within patriarchal conditions? If history is not given but constructed, how does one create feminist genealogies that will acknowledge these myriad influences and circumstances? What is the resonance of these practices today?

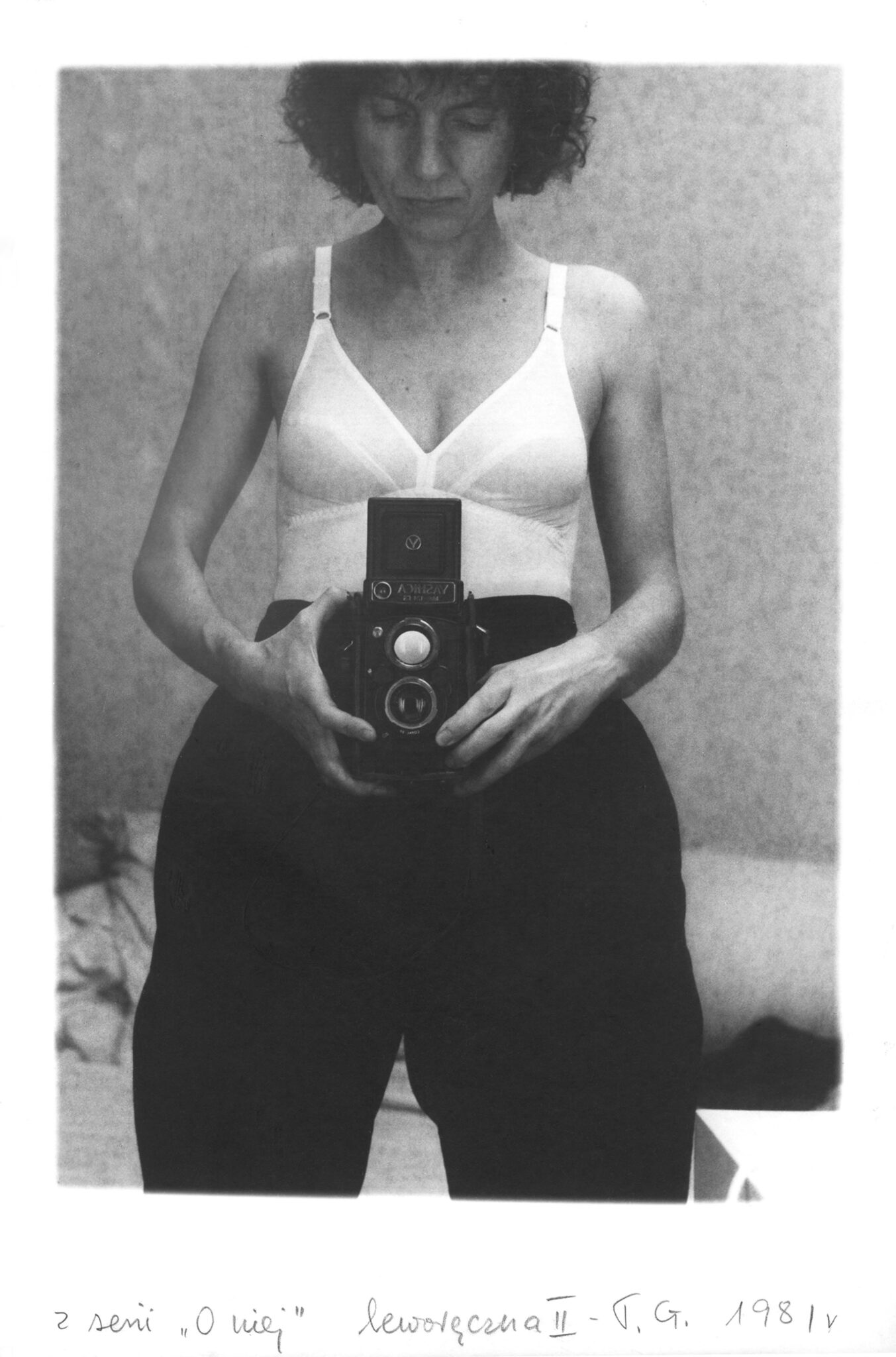

In this essay, I wish to problematize how artists from the People’s Republic of Poland (PRL), such as Natalia LL, Teresa Tyszkiewicz, Ewa Partum, Teresa Gierzyńska, and others, moved beyond the analytical and essentialist paradigm of conceptual art toward the realm of tacit knowledge—dreams, emotions, and desires—and yet decisively and pragmatically interfered with the Communist reality and materialist experience of a female body. At the same time, at various points in their lives, they sought to transgress the representation of the feminine by weaving patterns of abstraction and repetition, much like the Victorian cybernetician Ada Lovelace, who noticed the algebraic formulae of the analytical engine in the Jacquard loom. 44 For a full analysis and analogy between Ada Lovelace’s computational thinking and the Jacquard loom, see Sadie Plant, Zeros and Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture (London: Fourth Estate, 1998). ↩︎ Furthermore, I aim to move beyond the antagonistic reading of the analytical versus the intuitive, and show how the aforementioned artists used these constraints to create leverage and break the binary loop between commodification and objectification, body and mind, form and content. What I hope to elucidate is a speculative project of sensual cybernetics, which aims to transgress bothessentialist conceptualism and identity politics. Considering contemporary debates about the issues of gender, technology, and representation, I will also demonstrate how in recent years sensual cybernetics have become a tool of enchanting the masculine-centric infrastructure of technology and practicing a more nonbinary, open-source approach to body and technology. Lastly, the sensual cybernetics elucidates in my opinion the ongoing tension women face in the contemporary politics of visibility—using one’s own image in art-making as a tool of self-determination, and conversely, as an exit from figuration toward abstraction and more opaque ways of representation.

Writing in 1962 about his concept of tacit knowledge, the British Hungarian philosopher, chemist, and polymath Michael Polanyi explained:

We are aware of… things inside our body in terms of the position, and motion of an object, to which we are attending. In other words we are attending from these internal processes to the qualities of things outside. Our own body is the only thing in the world which we normally never experience as an object, but experience always in terms of the world to which we are attending from our body. It is by making this intelligent use of our body that we feel it to be our body, and not a thing outside. 55 Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 10. ↩︎

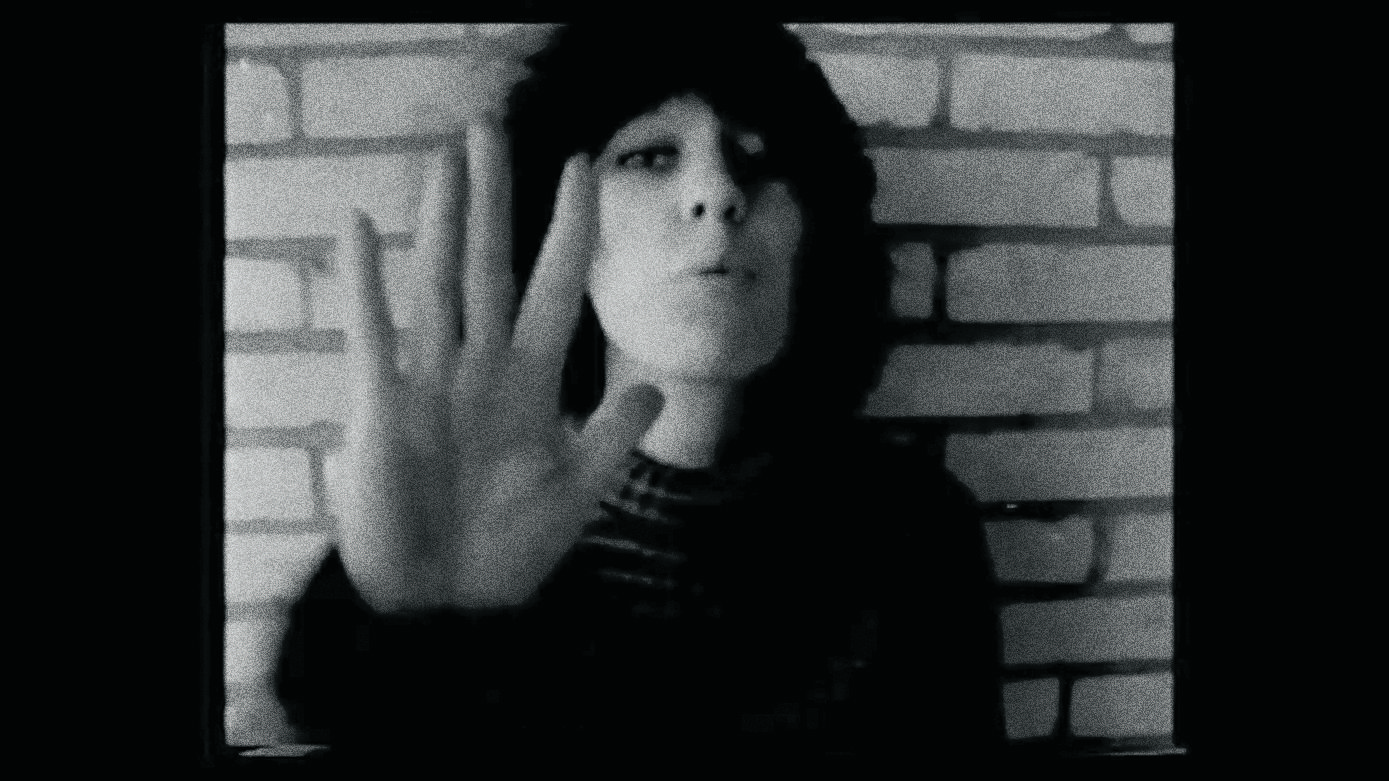

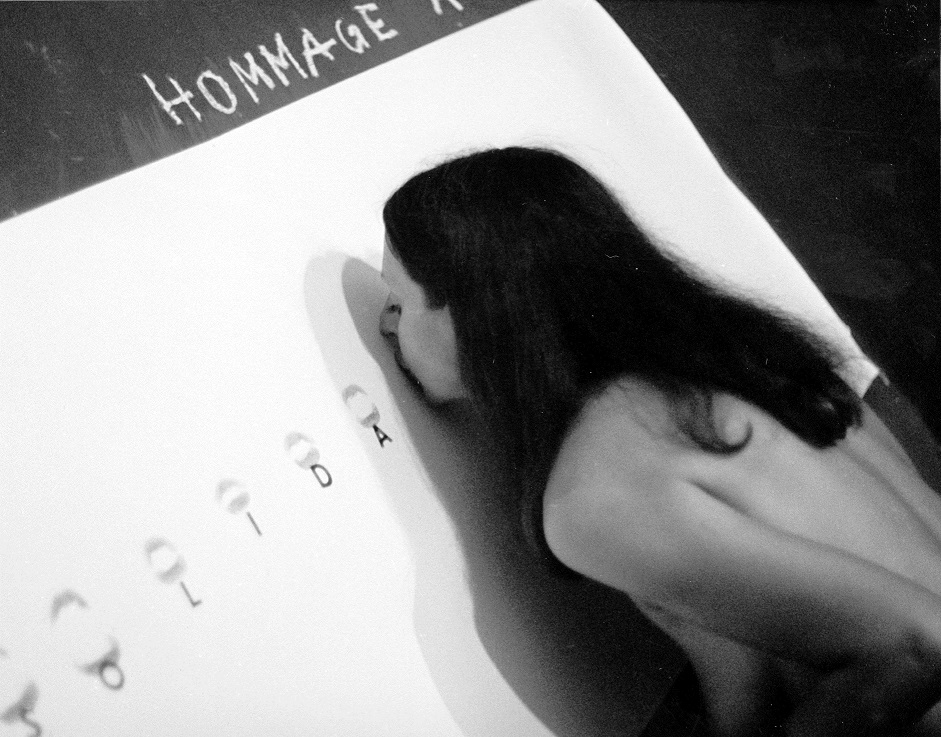

What does it mean to attend the outside world from inside the body? How do feminist artists transpose their bodily experiences into conceptual semiotics? As a woman, I know the experience of my own body as object intimately well, and I am similarly familiar with feelings of depersonalization and derealization—to feel oneself outside of the body is not an uncommon experience for oppressed groups and trauma survivors. Was this what the Polish artist Ewa Partum had in mind during her performance from 1979 titled ”Change. My Problem Is a Problem of a Woman”? [Fig. 2] At Galeria Art Forum (Łódź), Partum staged the process of aging on one half of her face and body with the help of makeup artists, which took place before the eyes of the assembled audience. The action was accompanied by recorded statements by Valie Export, Urlike Rosenbach, and by Partum herself, along with an inscription: ”the male artist has no biography. Because a woman artist—unlike a male artist—has a biography.”66 See Angelika Stepken, ed., Ewa Partum 1965–2001, exhibition catalogue (Karlsruhe: Badischer Kunstverein, (2001); Łukasc Ronduda, Polish Art of the 70s (Warsaw: Center for Contemporary Art, 2009); and Eva Partum, Change. My Problem Is a Problem of a Woman, video, Polish Performance Archive, Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, https://artmuseum.pl/en/archiwum/archiwum-polskiego-performansu/2516/126965. ↩︎ Partum, who began her artistic path with semantic and structural analysis of the moving image and concrete poetry rooted in postessentialist conceptualism, struggled with the paternalized reception of her work from the male-dominated avant-garde milieu for a long time. In fact, her performance unveils the faux-objectivity of conceptual art produced by „male artists with no biography”—in other words, the art that is seemingly universal and unencumbered by identity politics. This is why, already in 1971 and against this dogma, Partum attends the outside world from inside the body and asserts her place in feminist herstory. She formulates a conceptual statement on womanhood at the linguistic level and speaks in her own name: „My touch is a touch of a woman.”77 This iconic statement from Partum’s conceptual poem is part of a 1971 work that combines text with lip imprints. See also Ewa Gorzadek, trans., „Ewa Partum,” Culture.pl, https://culture.pl/en/artist/ewa-partum. ↩︎ As part of her videoperformance Tautological Cinema (1973), she signs this poetic utterance with an imprint of her blood-red lips, a trace of corporeality turned into a visual sign.

Because of the perceived overidentification with the body, or „biography,” to borrow Partum’s term, patronizing allegations were regularly made against artists whose works provided commentary on the female experience, as if women artists specialized in feeling rather than thinking. It was only third-wave feminism that welcomed those introspective and confessional attitudes, introducing unceremonious feminine affectivity into the language of art and humanities in order to treat it as an object that merits formal and aesthetic analysis.

When observing the trace of Partum’s painted mouth, which remained slightly parted, arranged in a vertical visual poem along with words written on paper, I am reminded of what the performance theorist Rebecca Schneider articulated in her research on gesture, repetition, and ephemerality. The author introduces the metaphor of a hand raised in a gesture of evocation, and uses this enigmatic figure to pose the question of whether a performative event (or gesture) from the past can serve as a script for the future. Asking ”How long can a call wait for a response?,” Schneider weaves together contemporary artworks that focus on gesture and hands, but also reconstructions of historical events and negative handprints from the Paleolithic era found in caves.88 Rebecca Schneider, ”Lithic Liveness and Agential Theatricality,” plenary session at the American Society for Theatre Research (November 22, 2014); see also Schneider, Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment (London: Routledge, 2011). ↩︎ Schneider reflects on what plays out in that highly peculiar space between call and response, between invocation and acknowledgment, where a call by gesture preserves its temporal interval and leaves time for an echo. Challenging the notion that performance passes and all that remains after it is documentation, the author asks what happens in the performative suspension between sender and receiver. For whom do her lips call, and what do they want?

Those are the lips of Medusa’s kiss, the lips of Marilyn, the illuminated ”Lamp-bouche” (1966) of Alina Szapocznikow. It’s the ephemeral transmission between her mouth, the mouth of Marcolla’s ”Kiss” (1975) and the actress’s mouth in Natalia LL’s Consumer Art (1972–1975)—the mouth that licks, chews, and bites as it pleases. Her touch is the touch of every feminist killjoy who ever dared to speak out loud.

But if the body remains at the core of feminist art, it is also its double bind, one that haunted women conceptual artists of the era until subsequent generations of feminists reclaimed it like an echo after an invocation. Because of the perceived overidentification with the body, or „biography,” to borrow Partum’s term, patronizing allegations were regularly made against artists whose works provided commentary on the female experience, as if women artists specialized in feeling rather than thinking. It was only third-wave feminism that welcomed those introspective and confessional attitudes, introducing unceremonious feminine affectivity into the language of art and humanities in order to treat it as an object that merits formal and aesthetic analysis. To paraphrase the words of the writer Chris Kraus: „Emotions are so terrifying. The world cannot believe that they can be cultivated as a discipline, formally.”99 Chris Kraus, quoted in Leslie Jamison,”This Female Consciousness: On Chris Kraus,” New Yorker (April 9, 2015), https:// www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/this-female-consciousness- on-chris-kraus. ↩︎

Many artists in the West—from 1990s feminist art icons such as Tracey Emin, Frances Stark, and Sophie Calle to Amalia Ulman, Rachel Maclean, Petra Collins, and other artists of the younger generation—have deliberately appropriated the tropes of raw female affectivity and have abandoned the approach of directly confronting patriarchal rhetoric, opting instead for pathos and openly sentimental expressions of emotion, in an attempt to assume control over representations of the female experience. But this approach was considered a „luxury” of navel-gazing, and was hardly present in Central and Eastern European countries in the first decade after the fall of Communism. Artists such as Katarzyna Kozyra, Katarzyna Górna, and Alicja Żebrowska, who found themselves in the transitory stage from state socialism to turbocapitalism, had to deal with new forms of patriarchy: the restrictions over reproductive rights, the influence of Catholic Church, and gender inequality in the workplace.

Of equal importance is the fact that Poland didn’t experience the sexual revolution that many Western countries did following the social reforms of the late 1960s, therefore the early 1990s saw the retraditionalization of sexual politics and the policing of women’s bodies. This is perhaps why the practices of the abovementioned pioneers of the so-called critical art were preoccupied more with deconstruction of mechanisms of power than with introspective, confessional attitudes that are now associated with third-wave feminism.

Artists such as Katarzyna Kozyra, Katarzyna Górna, and Alicja Żebrowska, who found themselves in the transitory stage from state socialism to turbocapitalism, had to deal with new forms of patriarchy: the restrictions over reproductive rights, the influence of Catholic Church, and gender inequality in the workplace.

Another paradox can be traced to the fact that already in the 1970s, the patriarchal fetishization of the female body denied women artists agency whenever they wished to pursue a more structural and analytical approach—for example, by seeking models of agency that could be found in technical reason, desubjectivization, and abstraction. When commenting on the popular reception of her performances, Partum expressed her dissatisfaction with these double standards:

„In their interpretations, many critics concentrate on the use of my naked body in my actions without actually understanding that for me it was a matter of creating a sign: a sign pointing into one direction. It was a tautological and not, as so many are inclined to believe, an egocentric strategy. Even in such an extreme situation like in the performance Stupid Woman [1981][Figs. 6, 7] where I kiss hands of members of the audience, pour alcohol over my head, write with whipped cream on the floor „sweet art”—in other words act like a drunk and stupid woman—I’m completely in control over my body. My naked body is merely a tool”.1010 Ewa Partum, quoted in „On historicizing conceptualism and the interpretation of feminism. A conversation with Ewa Partum,” interview by Karolina Majewska, Obieg.pl (August 4, 2014),https://archiwum-obieg.u-jazdowski.pl/english/31894. ↩︎

Her body is merely her tool. In today’s era of online selfactualization, the selfie as a medium of bearing witness to one’s own bodily and emotional states is mediated through the formatting infrastructures of social media—the Instagram grid, the front camera of an iPhone, filters, and digital enhancements. As Nicholas Mirzoeff observed, the 2.0 technological revolution launched formerly elite practices such as photography and conceptual art into the realm of global visual culture, and the unprecedented freedom of communication and expression enabled many visual artists to create their own presentation channels and community spaces.1111 Nicholas Mirzoeff, How to See the World (New York: Basic Books, 2016), 31. ↩︎ But do we really own the means of production in the ever-more privatized social media space?

At the core of Hansen’s radical theory was an assumption that art and architecture must repudiate the dominant and hierarchical ”closed form” which, as a general rule, stipulates a subordinated subjectivity and is subjugated to the level of a passive element in a larger habitat.

On the other hand, for the historical artists whose practice lends itself to feminist analysis through the codes of selfportraiture, self-determination, and the performance of societally enforced roles and norms, an interest in photography and expanded cinema arose from conceptual investigations into transparent and objective mediums of registering reality. Though authors such as Polanyi and Gregory Bateson, the latter whose cybernetic writings on love I have included in the introduction, were not translated into Polish until the 1990s, the generation of Eastern European artists from the 1970s was well accustomed to cybernetics and information theory. Numerous new categories of contact between the viewer and the artwork appeared in artistic actions through concepts of semiology, praxeology, and game theory, which were introduced at the philosophy department of the University of Warsaw by professor Tadeusz Kotarbiński. His teachings on praxeology, alongside terms like „input,” „output,” and „feedback loop,” were very popular among fine arts students in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For example, the key figures of the Warsaw neo-avant-garde—KwieKulik (Przemysław Kwiek and Zofia Kulik) [Fig. 8], Jan S. Wojciechowski, Jan Świdziński, and Marek Konieczny—went as far as to attempt establishing a Section for Aesthetics at the Polish Society of Cybernetics.1212 See Łukasz Ronduda and Georg Schöllhammer, eds., Zofia Kulik & Przemyslaw Kwiek: KwieKulik (Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 9. To fully comprehend the popularity of cybernetics in Polish neo-avant-garde art, one must recognize the influence of a wider phenomenon taking place in Poland during the 1970s, namely the significance of the Open Form theory, propagated by architect and theorist Oskar Hansen. His paradigm initially emerged in the wake of late modernists’ debates on architecture, and was subsequently appropriated through experiments on performance, video, and process art by a group of artists studying under Hansen in the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, at his Atelier of Solids and Planes. At the core of Hansen’s radical theory was an assumption that art and architecture must repudiate the dominant and hierarchical ”closed form” which, as a general rule, stipulates a subordinated subjectivity and is subjugated to the level of a passive element in a larger habitat. As Ronduda notes, the main paradigm of the theory fostered by Hansen was a concept of subjectivity that ”remained in a constant process of evaluation and interaction with the surrounding world.” When applied to the sphere of visual arts, the Open Form proposed a dialogical mode of communication between the artist and the spectator (recipient), and preconfigured the strategies of the emerging neoavant- garde. For a comprehensive presentation of Hansen’s theory in English, and interviews with Hansen and Hans Ulrich Obrist, see Oskar Hansen, Towards Open Form ”Ku formie otwartej, ed. Jola Gola (Frankfurt am Main: Revolver Archiv fuer aktuelle Kunst, 2005); and Lukasz Ronduda and Florian Zeyfang, eds., 1,2,3 Avant-Gardes: Film/Art between Experiment and Archive (Warsaw: CCA Ujazdowski Castle Center in Warsaw/Sternberg Press, 2007). ↩︎

It is not a coincidence that Polish neo-avant-garde artists such as Teresa Gierzyńska and Zofia Kulik studied at Oskar Hansen’s Atelier of Solids and Planes (known for progressive pedagogy based on modernist ideals, feedback, andcommunication), while Teresa Tyszkiewicz attended the Department of Technics and Mechanics at Warsaw Polytechnics. In one of Gierzyńska’s early exercises at Hansen’s studio in the academic year of 1969, the artist scraped the emulsion off of an undeveloped 35mm filmstrip to construct a visualization of a music piece, which was played out loud at the studio. Though the tape has not survived, Gierzyńska also made prints—photograms with visual interventions, which weaved complex patterns of information together like a cybernetic Jacquard structure. Hansen was deeply impressed by Gierzyńska’s project, and even arranged her visit to the Polish Radio Experimental Studio, a pioneering center for electroacoustic music known for experiments with tape, analog synthesizers, and musique concrete. […]

„Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s–1980s”, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, USA

This excerpt is from the book Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s–1980s, edited by Pavel Pys. Foreword by Mary Ceruti. Contributions by Ivana Bago, Dušan Barok, Anna Daucíková, Michal Grzegorzek, Libuše Jarcovjáková, Daniel Muzyczuk, Alexandra Pirici, Pavel Pys, Karol Radziszewski, Kathleen Reinhardt, Natalia Sielewicz.

Przypisy

Stopka

- Osoby artystyczne

- Milan Adamciak, Autoperformationsartisten, AWACS, Lubomír Benes, Sándor Benkö, A.E. Bizottság, Vladimir Bonacic, Geta Bratescu, Adina Caloenescu, Zdenka Cechová, Vera Chytilová, Lutz Dammbeck, Jan Dobkowski, Sherban Epuré, Barbara Falender, Lászlo Fehér, Stano Filko, AG Geige, Teresa Gierzy?ska, Karpo Godina, Tomislav Gotovac, Ion Grigorescu, Wiktor Gutt & Waldemar Raniszewski, Gino Hahnemann, Heino Hilger, Károly Hopp-Halász, Janós Istvány, Sanja Ivekovic, Libuse Jarcovjáková, Zeljko Jerman, Krzysztof Jung, Eva Kmentová, Milan Knízák/AKTUAL Group, Július Koller, Jirí Kovanda, Gyula Konkoly, Kryzys, Jolanta Marcolla, Florin Maxa, Tomislav Mikuli?, Teresa Murak, Katalin Ladik, Matei Lazarescu, Natalia LL, Ana Lupas, Dóra Maurer, Simon Menner, Andrzej Mitan, Kolomon Novak, Ewa Partum, Plastic People of the Universe, Polish Radio Experimental Studio, Queer Art Institute, Józef Robakowski, Jerzy Rosolowicz, Akademia Ruchu, Zbigniew Rybczy?ski, Alina Szapocznikow, Peter stembera, Krzysztof Wodiczko.

- Osoby autorskie

- red. Pavel Pys

- Tytuł

- Multiple Realities: Experimental Art in the Eastern Bloc, 1960s–1980s

- Miejsce

- Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

- Wydawnictwo

- Walker Art Center

- Data i miejsce wydania

- 2023, Minneapolis

- Indeks

- A.E. Bizottság Adina Caloenescu AG. Geige Akademia Ruchu Alina Szapocznikow Ana Lupas Andrzej Mitan Autoperformationsartisten AWACS Barbara Falender Dora Maurer Eva Kmentová Ewa Partum Florin Maxa Geta Brătescu Gino Hahnemann Gyula Konkoly Heino Hilger Ion Grigorescu Jan Dobkowski Janós Istvány Jerzy Rosołowicz Jiří Kovanda Jolanta Marcolla Józef Robakowski Julius Koller Károly Hopp-Halász Karpo Godina Katalin Ladik Kolomon Novak Kryzys Krzysztof Jung Krzysztof Wodiczko Lászlo Fehér Libuše Jarcovjáková Lubomír Benes Lutz Dammbeck Matei Lazarescu Milan Adamciak Milan Knízák/AKTUAL Group Natalia LL Peter stembera Plastic People of the Universe Polish Radio Experimental Studio Queer Art Institute Sándor Benkö Sanja Iveković Sherban Epuré Simon Menner Stano Filko Teresa Gierzy?ska Teresa Murak Tomislav Gotovac Tomislav Mikuli? Vera Chytilová Vladimir Bonačić Wiktor Gutt & Waldemar Raniszewski Zbigniew Rybczy?ski Zdenka Cechová Željko Jerman