„#dziedzictwo” w Muzeum Narodowym w Krakowie / „#heritage” at the National Museum in Krakow

For English version scroll down

PL

Wystawa #dziedzictwo w MNK jest głosem w toczącej się debacie na temat polskiego dziedzictwa. W przededniu stulecia odzyskania niepodległości debata ta zyskuje nową dynamikę, skłaniając do postawienia pytania o nas samych, o to, jak definiujemy naszą historię, dorobek cywilizacyjny, specyfikę kultury narodowej i jej związki z otaczającym nas światem.

Tytuł wystawy podkreśla konieczność aktualizacji wydarzeń historycznych przez odwołanie do znaku hasztag stosowanego w przestrzeni internetowej. Za jego pomocą oznacza się treści istotne, ale i komentowane dowolnie przez użytkowników sieci, co odnosi się do idei otwartej dyskusji na temat tego, co jest naszym dziedzictwem. W tym kontekście należy też postrzegać Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie – jako instytucję, która przez całą swoją skomplikowaną historię tworzyła i tworzy materialny zapis naszego dziedzictwa. Stąd też na wystawie znalazły się wyłącznie obiekty z kolekcji krakowskiego Muzeum, które to zbiory w szczególny sposób definiują polską kulturę. Hasztag to tylko współczesne oznaczenie dyskusji, która rozpoczęła się w chwili powołania Muzeum uchwałą Rady Miasta Krakowa 7 października 1879 roku.

Wystawa nie jest reprezentatywnym wyborem dzieł z muzealnej kolekcji, ale jej interpretacją. Podkreślanie kulturowej ciągłości i odnajdywanie stałych elementów narodowej tożsamości w znanych i nieznanych dziełach z różnych epok, nawet w okresach braku politycznej suwerenności, to najważniejsza teza wystawy. Jej konstrukcja oparta została na czterech kategoriach zaczerpniętych z antropologicznych i historycznych studiów nad kulturami narodowymi. Są to „geografia”, „język”, „obywatele” i „obyczaj”, przy czym pierwsza odnosi się do terytoriów, z którymi dana kultura się wiąże i traktuje jako własne, druga podkreśla rolę języka w definiowaniu odrębności narodowych, trzecia opisuje tych, którzy z daną kulturą się utożsamiają, a czwarta uzmysławia, że z perspektywy historycznej narody definiować można przez odniesienie do ich źródeł kulturowych, a nie kategorii etnicznych.

Pierwsza kategoria odnosi się do znaczenia geograficznej lokalizacji, w której rozwija się kultura – i to zarówno z uwagi na warunki naturalne, jak i relacje centrum–peryferia czy kontekst geopolityczny. Dla polskiej tożsamości kwestie geograficzne mają zasadnicze znaczenie, przede wszystkim ze względu na zmieniające się granice polityczne kraju, a także liczną emigrację rozsianą po całym świecie, co powoduje, że Polska może być, jak chciał Alfred Jarry, „nigdzie”, a z drugiej strony niejako wszędzie: ślady polskich obecności odnaleźć można na wszystkich kontynentach. Stąd na wystawie znalazły się historyczne mapy pokazujące Rzeczpospolitą w okresie jej największego rozkwitu, ale i opis pielgrzymki Mikołaja Krzysztofa Radziwiłła do Jerozolimy z 1601 roku, mapa Australii z najwyższym szczytem nazwanym przez jego odkrywcę Pawła Edmunda Strzeleckiego Górą Kościuszki czy regulamin kolonii polskiej w Adampolu w pobliżu Stambułu, założonej dla polskich emigrantów po powstaniu listopadowym. Ta część wystawy podkreśla, że Polacy nigdy nie ograniczali swojej działalności do terenów uważanych za etnicznie polskie, co więcej, gdyby chcieć zakreślić mapę obejmującą miejsca, w których w różnym stopniu obecna była kultura polska, musielibyśmy wskazać cały świat.

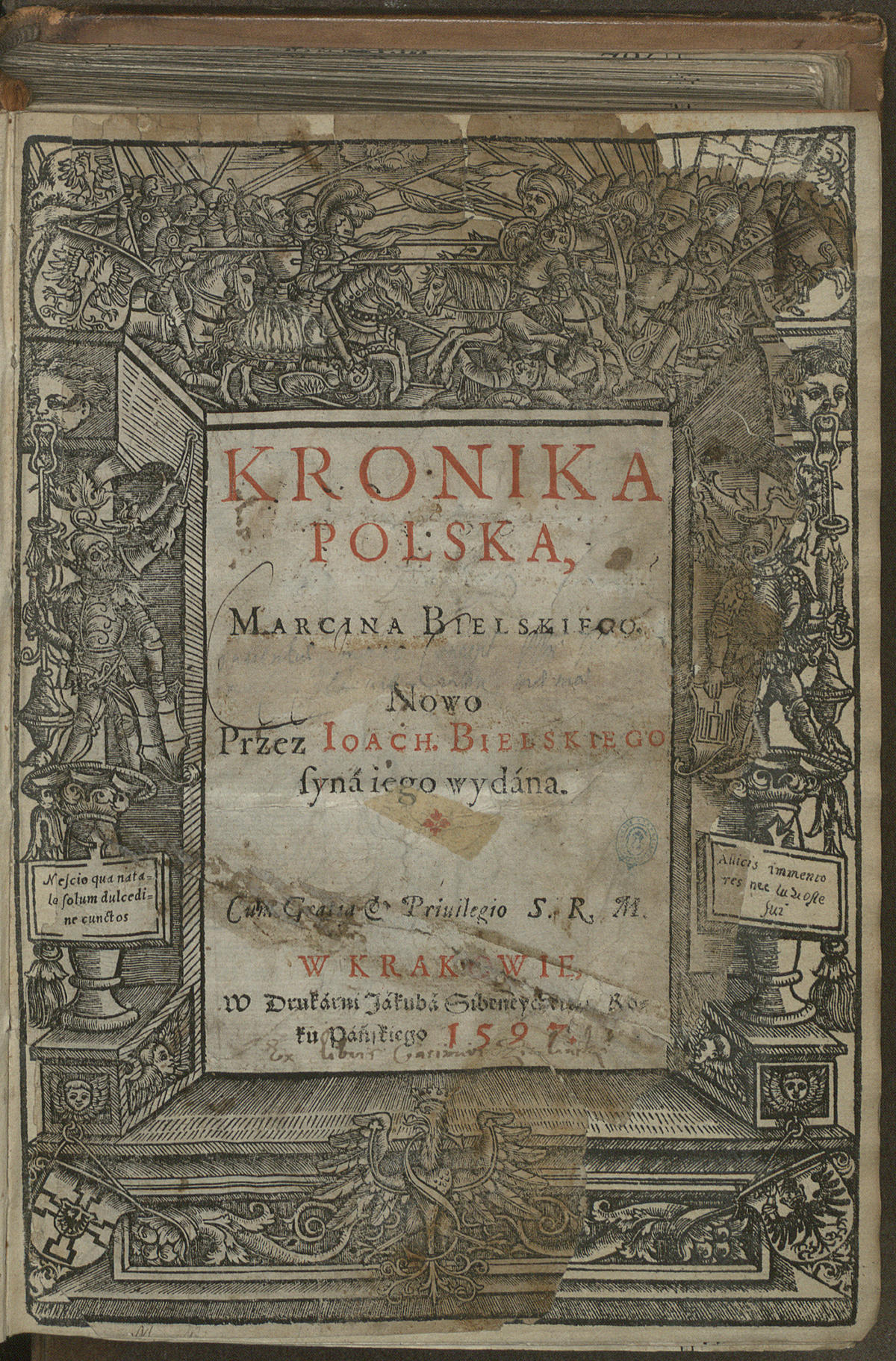

W historii kultury polskiej słowu pisanemu nadawano od dawna najwyższą rangę, ceniąc je wyżej niż inne dziedziny sztuk. Część wystawy poświęconą językowi otwiera alfabet polski, pokazany za pośrednictwem ilustracji Jana Marcina Szancera do książki Wandy Chotomskiej Abecadło krakowskie (1962), znalazły się tu też egzemplarze najbardziej znanych dzieł z historii literatury polskiej od wydania Odprawy posłów greckich Jana Kochanowskiego z 1585 roku po XIX- i XX-wieczną poezję oraz prozę. Ale nie tylko język polski włączono do narodowej kolekcji. Odnaleźć tu można język łaciński, widniejący na denarze z czasów Bolesława Chrobrego, którego określono mianem „Princes Poloniae”, a także zabytki innych języków, którymi posługiwano się na terenach historycznej Rzeczypospolitej, w tym litewskiego, starocerkiewnosłowiańskiego i hebrajskiego, a także esperanto.

W ramach polskiego dziedzictwa mieszczą się zatem zarówno zabytki języka polskiego stanowiące fundament polskiej tożsamości, jak i dokumenty potwierdzające wieloetniczność Rzeczypospolitej, a także dowody poszukiwania nowego, wspólnego dla wszystkich nacji języka.

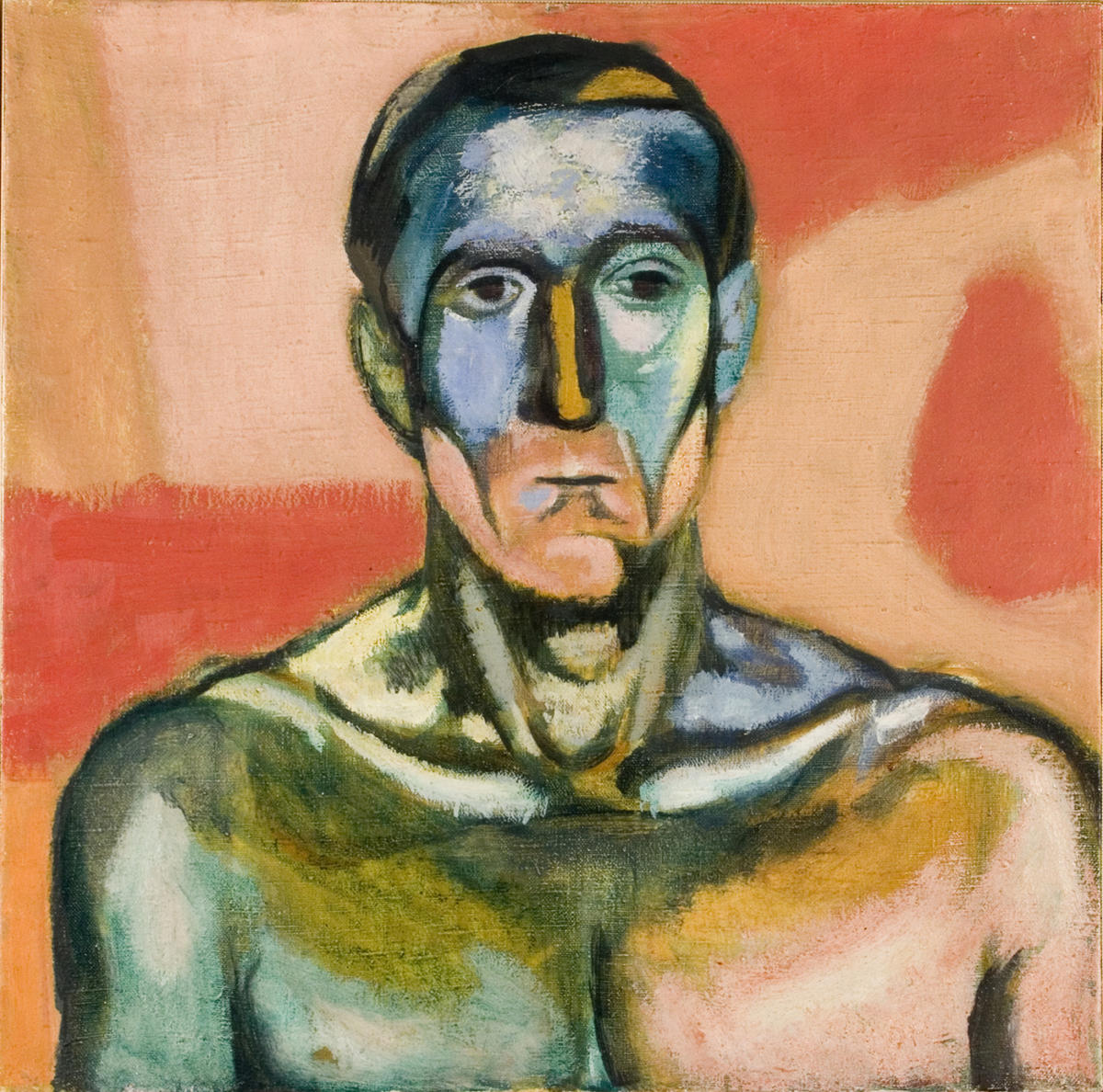

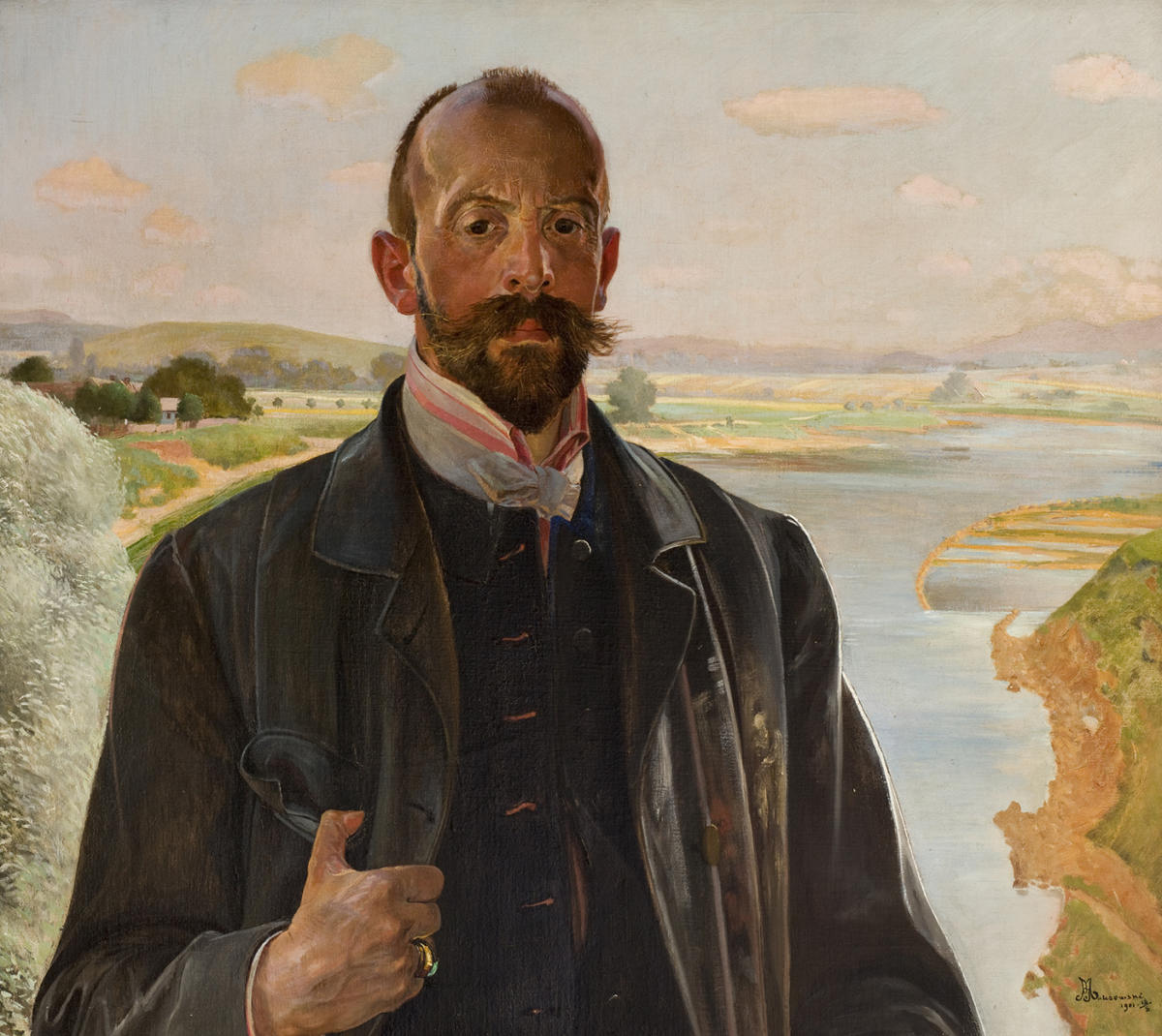

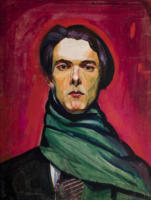

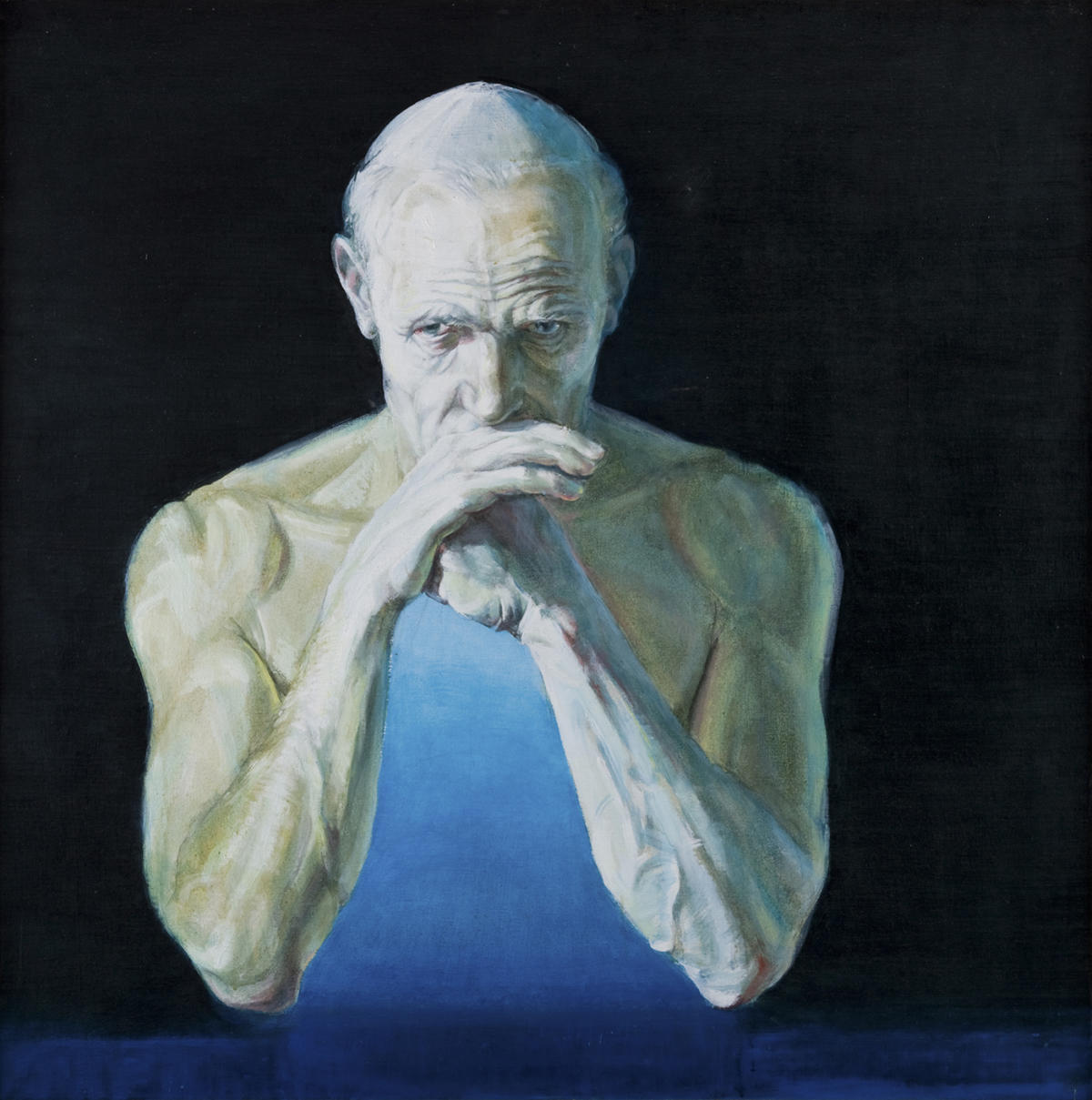

W kategorii „obywatele” mieszczą się wizerunki tych, których z perspektywy kolejnych twórców kolekcji Muzeum Narodowego w Krakowie można uznać za natione Polonus, od anonimowych mieszczan z Warszawy, małopolskich i wielkopolskich chłopów przez robotników z Łodzi, tatrzańskich i huculskich górali, żydowskich rabinów, ormiańskich kolekcjonerów, romskich muzyków po królów, królowe i innych. W ten sposób kolekcja może być postrzegana jako najbardziej egalitarny w założeniu obraz tych wszystkich, którzy uznawali się za polskich obywateli, dowodząc, jak otwarta była to kategoria i jak atrakcyjne okazywało się dla nich polskie dziedzictwo.

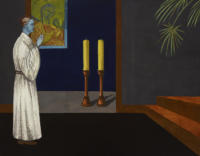

Czwarta kategoria odnosi się do tego, co można utożsamić z polskim obyczajem. Ten fragment pokazuje najbardziej zwyczajne elementy polskiego dziedzictwa, od religijności po wyposażenia mieszkań, rytuały towarzyskie, nakrycie stołu, opakowania, stroje, rozrywki, banknoty etc., stanowiące o tym, co Zbigniew Herbert nazwał potęgą smaku. Obyczaj polski często się wiązał także z walką zbrojną i etosem wolnościowym, w imię hasła „O wolność naszą i waszą”. Muzeum posiada także najwybitniejsze osiągnięcia kultury polskiej cenione w świecie, jak egzemplarz dzieła Kopernika O obrotach ciał niebieskich, mapy księżyca Jana Heweliusza dedykowane Janowi III Sobieskiemu, zapis nutowy autorstwa Fryderyka Chopina czy zegarki wykonane przez Józefa Patka z wizerunkami polskich bohaterów. W tej kategorii mieści się także pejzaż Rafała Malczewskiego pokazujący budowę COP-u oraz traktat Andrzeja Frycza Modrzewskiego De Republica emendanda, przypominające o modernizacyjnych osiągnięciach państwa polskiego i polskiej refleksji na tematy ustrojowe.

Krakowska wystawa to „skarbnica pamięci”, do której wraca się po to, aby inspirowała czasy nam współczesne, a przede wszystkim pozwalała się zastanowić, jakiego dziedzictwa jesteśmy spadkobiercami i w jaki sposób potrafimy dopisać kolejny rozdział w jego historii.

ENG

The exhibition #heritage at the National Museum in Krakow is a contribution to a discussion on the subject of Polish identity. On the eve of the centenary of Poland’s regaining independence this debate has become more dynamic, provoking reflection on ourselves, on the way we define our history, civilisation achievements, specificity of national culture and its relations with the surrounding world.

The title of the exhibition emphasises the necessity to revise historical events by referring to the hashtag sign, commonly used in social networking either to mark important information or to comment on any information, which concerns the idea of an open discussion about our heritage. In this context the National Museum in Krakow should be perceived as an institution which has been recording our heritage in a material form throughout its complicated history. Hence the exhibition features objects exclusively from the collection of the Krakow Museum, as these holdings define Polish culture in a special way. The hashtag is nothing but a contemporary marking of the discussion which has been held since the establishment of the Museum according to the resolution adopted by the Krakow City Council on 7 October 1879.

The emphasis placed on cultural continuity and finding recurring elements of national identity in both well-known and little-known works from different eras, even during the periods of no political sovereignty, is the most important thesis of the current exhibition. Its structure is based on four categories taken from anthropological and historical studies of national cultures. These are: “territory”, “language”, “citizens” and “custom”, the first one concerning the areas associated with a given culture and regarded by it as its own, the second one stressing the role of language in defining the national identity, the third one describing people associating themselves with a given culture and the fourth one making one aware that from the historical perspective nations can be defined by referring to their cultural sources rather than ethnical categories.

The first category concerns the significance of geographical location in which culture develops – both taking into account natural conditions and the centre–periphery relationship or geopolitical context. Territorial aspects have been of key significance for Polish identity, above all because of the changing political borders and a great number of emigrants scattered all over the world. Therefore the exhibition features historical maps showing not only Poland in its heyday, but also a description of Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł’s trip to Jerusalem in 1601, a map of Australia with its highest mountain named Mount Kościuszko by its discoverer Paweł Edmund Strzelecki and the regulations of the Polish colony in Adampol near Istanbul, founded for the Polish émigrés after the November Uprising. This part of the exhibition shows that Poles never limited their activity to the areas regarded as ethically Polish. Moreover, if one wanted to map out the places where Polish culture has been present, it would have to be the entire world.

In the history of Polish culture the written word has always been held in the highest esteem and valued more than the other arts. The part of the exhibition devoted to language starts with the Polish alphabet, shown with the use of illustrations by Jan Marcin Szancer for the book by Wanda Chotomska Abecadło krakowskie [Krakow ABC] (1962). On display are also copies of the most famous works of Polish literature, from Odprawa posłów greckich [The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys] by Jan Kochanowski, published in 1585, to 19th- and 20th-century poetry and prose. However, it is not only the Polish language that is included in the exhibition. Visitors can also see Latin – on a denarius from the time of Bolesław the Brave, called “Princes Poloniae”, and texts in other languages used within the territory of Poland throughout the centuries, including Lithuanian, Old Church Slavonic and Hebrew, as well as Esperanto. Polish heritage thus includes not only Polish texts, forming the foundations of Polish identity, but also documents evidencing both Poland’s multi-ethnic character and attempts at finding a new language that would be shared by all the nations.

The category “citizens” encompasses images of the people who from the perspective of the successive creators of the collection of the National Museum in Krakow may be considered natione Polonus: from anonymous Warsaw burgers, peasants inhabiting the historical regions of Małopolska [Lesser Poland] and Wielkopolska [Greater Poland], workers from Łódź, Tatra and Hutsul highlanders, Jewish rabbis, Armenian collectors, and Gypsy musicians, to kings and queens, as well as others. As a result the collection may be regarded as the most egalitarian picture of all those who thought about themselves as the Polish citizens, which confirms how open this category was and how attractive Polish heritage proved for them.

The fourth category concerns what can be associated with the Polish customs. This part shows the most common elements of Polish heritage, everything from religiousness to furnishings, social habits, ways of setting the table, packaging, clothes, entertainment, banknotes etc. determining what Zbigniew Herbert called the power of taste. The Polish custom was not infrequently connected with armed struggle and the ethos of freedom, in the name of the slogan “For Your Freedom and Ours.” The Museum can also boast the greatest achievements of Polish culture highly valued all over the world, like Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), Johannes Hevelius’s maps of the moon dedicated to John III Sobieski, Frederic Chopin’s musical notation and watches made by Józef Patek, decorated with images of Polish heroes. This category also includes a landscape by Rafał Malczewski showing the construction of the Central Industrial Region and Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski’s treatise De Republica emendanda, reminding about the modernisation achievements of the Polish state and Polish reflection on the issues concerning the political system.

The Krakow exhibition is a „treasury of memories”, where one returns to draw inspiration for contemporary times and above all which offers an opportunity to reflect on the nature of our heritage and think how we can add yet another chapter in its history.

Przypisy

Stopka

- Wystawa

- #dziedzictwo / #heritage

- Miejsce

- Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie / National Museum in Krakow

- Czas trwania

- 23.06.2017-07.01.2018

- Osoba kuratorska

- Andrzej Szczerski

- Strona internetowa

- mnk.pl