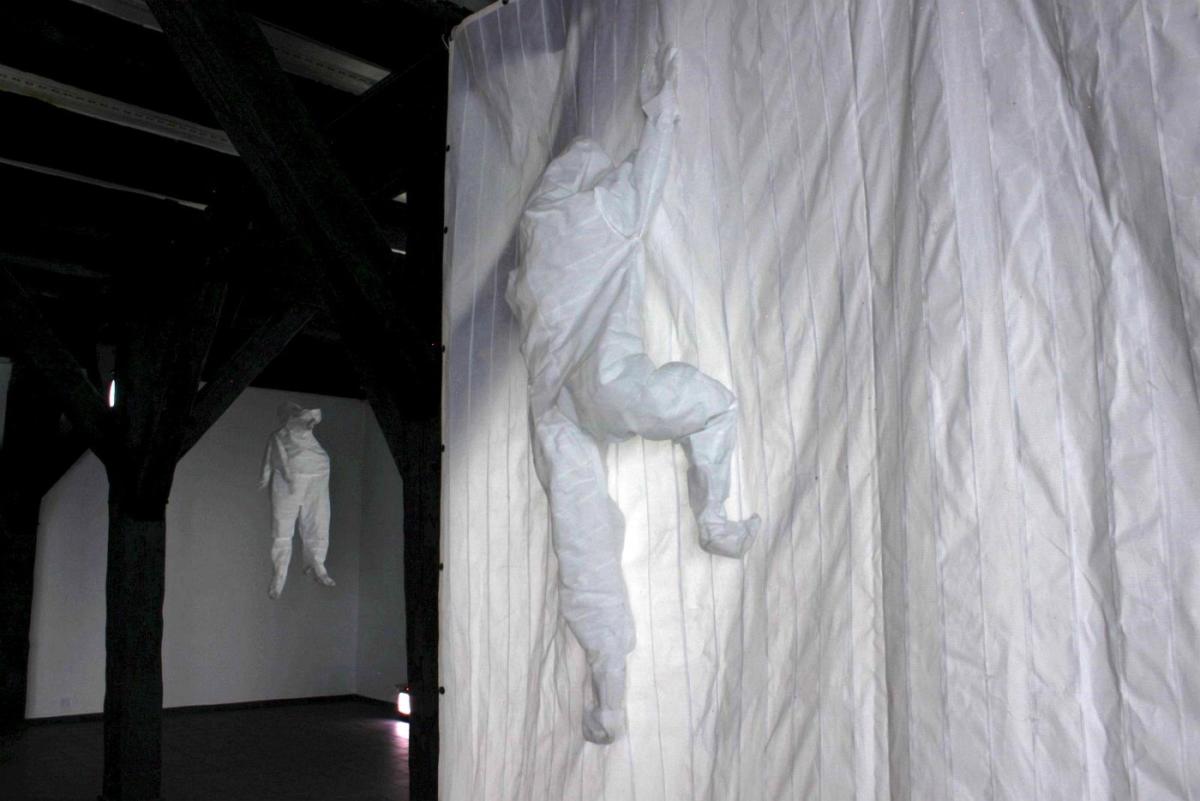

„Części pierwsze” Justyny Olszewskiej w Galerii Sztuki Wozownia / “Elementary Particle” Justyna Olszewska’s at Galeria Sztuki Wozownia

PL

(Do)tkliwa kondycja skóry

Justyna Olszewska w swoich pracach myśli poprzez skórę.[1] Postawa tego rodzaju jest bliska poglądom filozofa Viléma Flussera, który zaproponował filozoficzną dermatologię poszerzoną, traktującą o skórze jako o granicy między ja a światem.[2] Filozof ten postulował, że musimy się zmienić i stać się powierzchowni, byśmy w teorię wychodzili od samych siebie i widzieli wszystko ekstatycznie z perspektywy własnego ciała pokrytego skórą. Jego zdaniem powinny nas interesować powierzchnie, a nie rzekomo ukryte pod nimi tajemnice, gdyż tajemnica nie jest gdzieś głęboko schowana, lecz leży właśnie na powierzchni skóry. Skóra jawi się jako „przestrzenno-czasowe kontinuum”, które pulsuje równolegle z czasem, rozciąga się i zbiega w trzecim wymiarze, nie tracąc przy tym swojego charakteru powierzchni, a ponadto działa niczym „moja pamięć”, zapisując skaleczenia w formie blizn i szram. Flusser diagnozuje kryzys nauki i zachodnich modeli myślenia, opartych o obiektywizm i transcendencję, poprzez które nie da się wypowiedzieć doświadczeń i informacji, pozyskiwanych z perspektywy fenomenologicznej. Ta niemożność czyni nas z kolei wyobcowanymi wobec własnej skóry – czujemy się w niej jak w czymś dla nas obcym, wskutek czego jesteśmy wyobcowani także w świecie. Filozof zaproponował więc dermatologię filozoficzną jako rodzaj narzędzia, dzięki któremu proces wyobcowania zostanie odwrócony. Nakreślenie mapy skóry oraz rozwinięcie poszerzonej dermatologii filozoficznej powinno również stymulować pojawianie się nowych modeli myślenia i nauki, których jego zdaniem obecnie potrzebujemy.

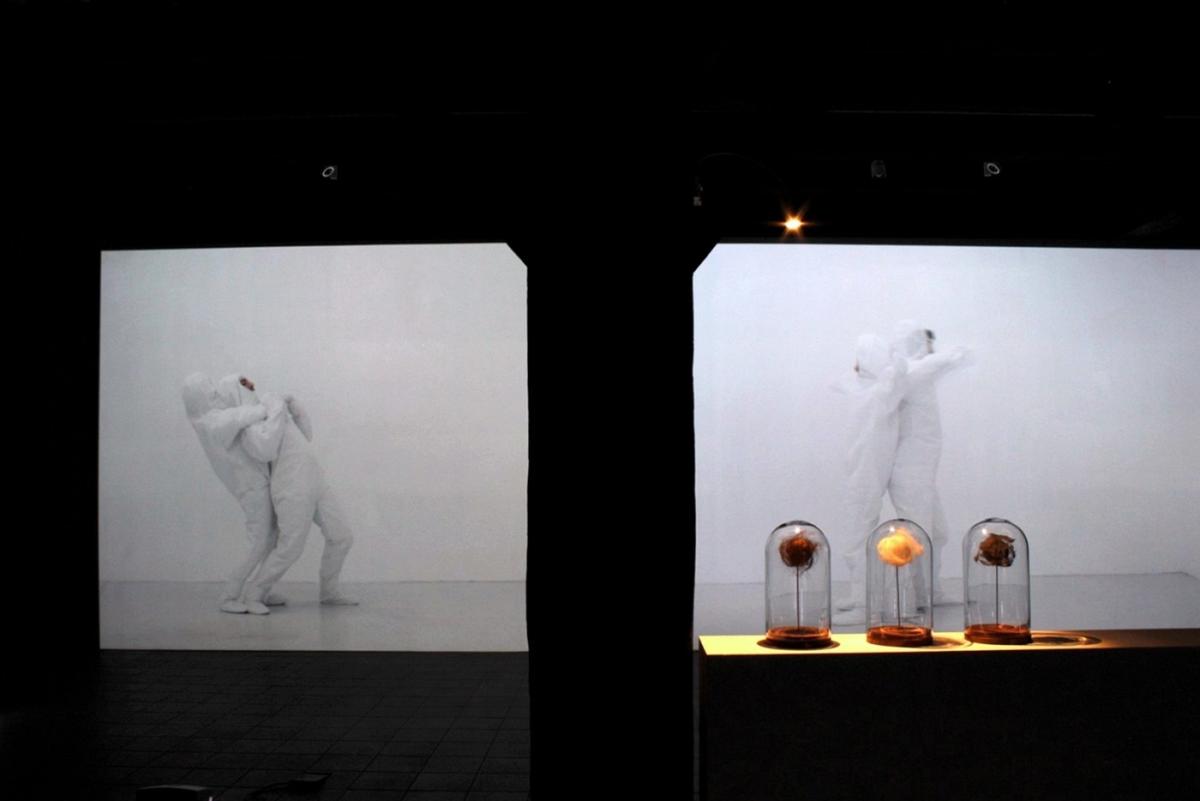

Olszewska porusza się z kolei najbliżej postrzegania skóry jako niezwykle wrażliwej granicy między ja a światem, na której tak wiele każdego dnia może się w naszym życiu wydarzyć. U dorosłego człowieka to w końcu przeciętnie aż 1,5-2 metry kwadratowe powierzchni, nieustająco wystawionej na dotyk. Barbara Stafford proponuje poszerzenie dermatologicznego projektu Flussera na obszar estetyki, propagując pojęcie dermatologii estetycznej.[3] Natomiast zdaniem Atsushi Tanigawy możemy mówić o semiotyce skóry, gdyż jest to miejsce, w którym dochodzi do wyjątkowo skomplikowanej wymiany i transferów pomiędzy wnętrzem a zewnętrzem.[4] Takie transfery czujnie śledzi i aranżuje w swoich dokamerowych performensach i obiektach także Olszewska, dla której w ramach projektu pokazywanego obecnie w Galerii Sztuki Wozownia w Toruniu ekwiwalentem skóry stają się powierzchnie z rzepowej taśmy.

Rzep – jak mówi znane powiedzenie – czepia się wszystkiego. Jest chwytliwy, wchodzi w natychmiastową interakcję z otoczeniem, „łapiąc” i kumulując na sobie zarówno to, co znajduje się w jego otoczeniu, jak i przylegając do napotkanych istot i przedmiotów. W naturze rzep to owoc łopianu, który w drodze ewolucji wykształcił haczyki wczepiające się w futra zwierząt, roznoszących w ten sposób jego nasiona.

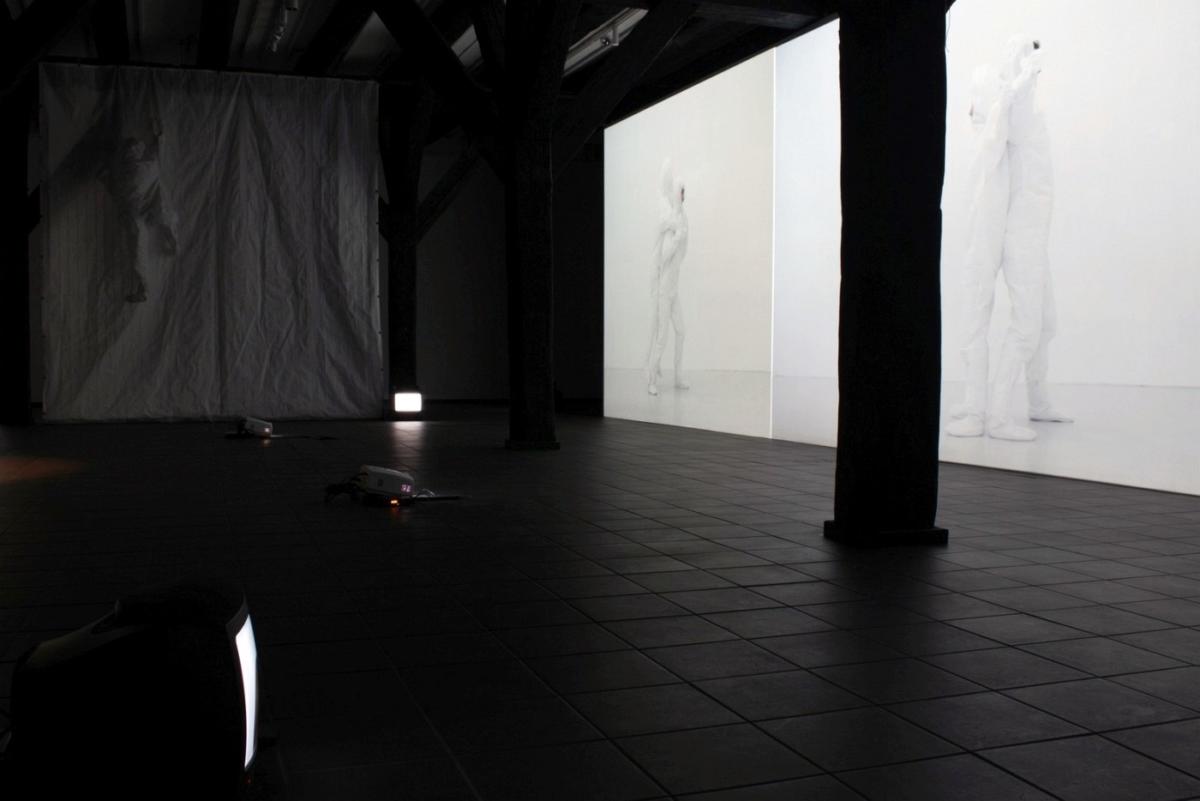

Dla Olszewskiej rzep staje się metaforą skóry jako granicy między ja a światem, na której codziennie dochodzi do szalenie skomplikowanych procesów. Mogą to być spektakularne rozkoszne czy bolesne zetknięcia z kimś innym. Mogą to być także efemeryczne i subtelne relacje z kurzem, własnymi wypadającymi włosami czy sierścią kota snującą się miękko po mieszkaniu i w efekcie otulającą nas niczym kożuch. Nasza skóra wiedzie bowiem własne, intrygujące życie, a my – szczelnie nią pokryci – często dostrzegamy jedynie jego niewielką – by nie powiedzieć – ułamkową – część. W realizacjach Olszewskiej skóra, postrzegana niczym pod lupą, staje się „czepliwa”, pozwalając nam z jednej strony łączyć się z drugim człowiekiem lub naszym otoczeniem; z drugiej zaś strony nieledwie boleśnie się od nich oddzielać. Momenty łączenia się rzepów są w tym wypadku intensywnym zwróceniem uwagi na owe sytuacje, gdy skóra styka się z czymś, wchodzi w bliski kontakt, a następnie – zapamiętawszy dotykiem to zetknięcie – odrywa się i odbudowuje granicę hermetycznie opasującą nasze ciała. Dlatego w dolnej sali Galerii Sztuki Wozownia niebagatelną rolę pełni przejmujący dźwięk rozrywanych rzepowych taśm, który wybrzmiewa zarówno jak sygnał rozdzielenia po doznanej bliskości, jak i jako hymn doznawanej ulgi czy uwalniania się, zwiastujący ponowne odzyskanie autonomii, gdy znowu bezpiecznie znajdujemy się we własnej skórze.

„Ciało jest okiem cyklonu, ośrodkiem koordynacji, stałym miejscem napięć w szeregu doświadczeń. Wszystko krąży wokół niego i jest odczuwane z jego punktu widzenia.”[5] Percepcja prac tego rodzaju przenosi się zatem w sferę sensomotoryczną, a w centrum tego procesu – zamiast chłodnej analizy – sytuuje się intensywność doznań, potęgowanych dodatkowo dźwiękiem.

Tak popularne obecnie skierowanie uwagi na powierzchnię i skórę inspirowane jest nie tylko badaniami z zakresu psychoanalizy, lecz również metaforami autorstwa między innymi Paula Valéry’ego, określającymi człowieka jako istotę ektodermiczną, której właściwa głębia paradoksalnie jest skórą. To przesunięcie zainteresowania z głębi na powierzchnię oraz z dualizmu wnętrze – zewnętrze na to, co pomiędzy nimi, wiąże się także ze sposobami definiowania tożsamości współczesnego człowieka. O tym „opowiadają” prace Olszewskiej, rozgrywające się w otoczeniu sterylnej bieli, która tym silniej kieruje uwagę na sedno sprawy: skórę jako przestrzenno-czasowe kontinuum, dzięki któremu kontaktujemy się ze światem i ze sobą nawzajem. Skóra zyskuje autonomię i ostentacyjnie zwraca na siebie uwagę. Parafrazując Kartezjusza, Olszewska zdaje się mówić: „Mam skórę, więc jestem. (Do)tkliwie jestem.”

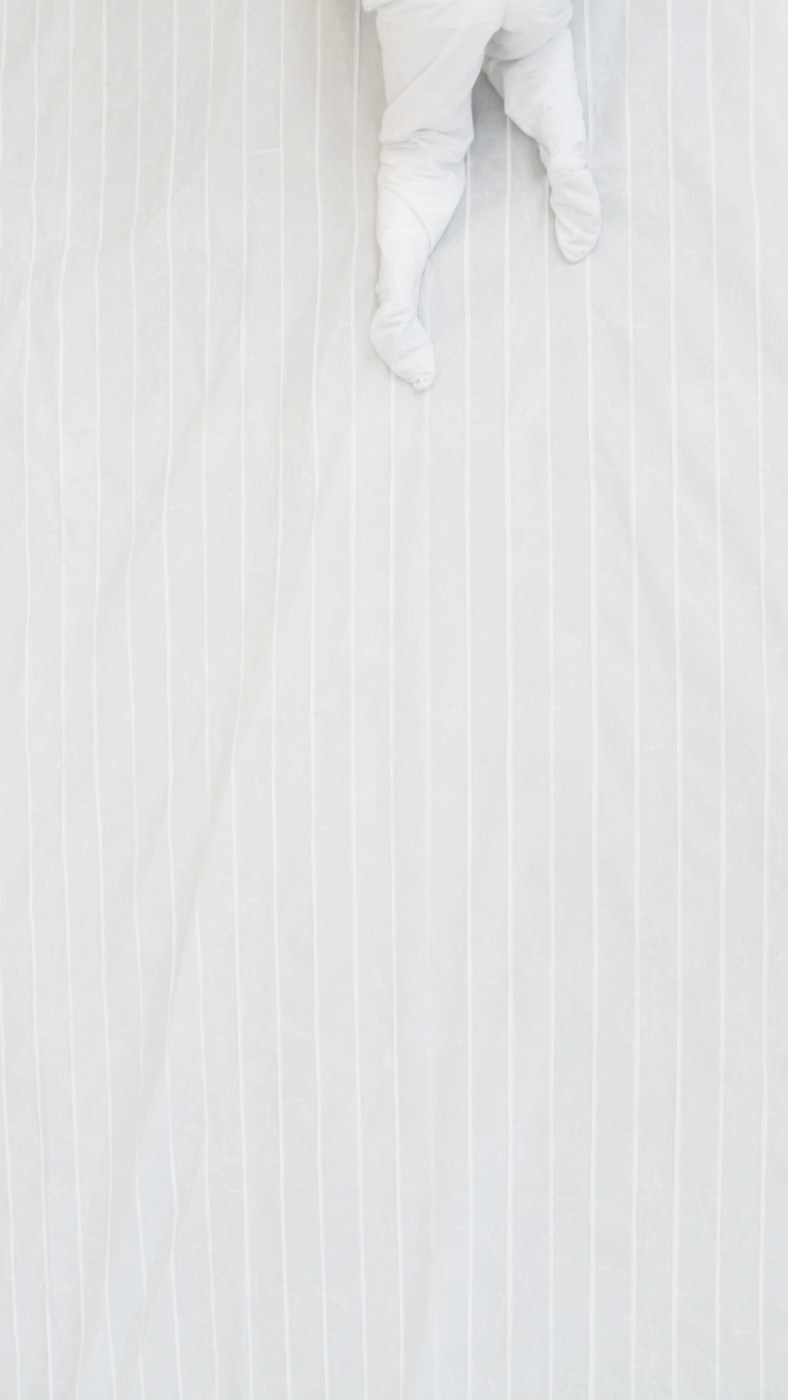

Skóra, niesprowadzona jedynie do niedorzecznych arabesek odcisków palców, jak ujął to Giorgio Agamben[6], staje się wszak mapą osobistych doświadczeń, której indywidualna topografia przypomina tekst dziennika spisywanego przez doznania. Każda jest więc niepowtarzalna i jedyna w swoim rodzaju, znaczona bliznami, otarciami, szramami i znamionami. Jej przedstawianie i analizowanie odwraca, opisany przez Flussera, proces wyobcowania wobec świata oraz pozwala wypowiedzieć doświadczenia i informacje, pozyskiwane z perspektywy fenomenologicznej. Także użyte przez Olszewską rzepy mają swoje „blizny”, wyszarpania, wydarcia, co widać na eksponowanym w ramach wystawy kombinezonie używanym wcześniej w trakcie dokamerowych performensów. Podobnie jak żywa skóra, nosi on ślady interakcji i transferów, zachodzących na granicy między ja a światem.

Motyw skóry – mimo iż z natury powierzchniowy – uruchamia więc złożone i wielowarstwowe pokłady znaczeń, związane z balansowaniem na granicy wnętrza i zewnętrza, sygnalizowaniem naszej cielesnej kruchości oraz próbami definiowania tożsamości w czasach ponowoczesnych. Uzmysławia nam również naszą śmiertelność, podatność na zranienia i choroby oraz stawia pytania o nasze relacje z innymi i środowiskiem, w którym żyjemy. Olszewska, podejmując ten wątek, być może sugeruje, że „cokolwiek się w życiu ludzkim liczy, liczy się tylko dlatego, że życie ludzkie ma kres, i że ludzie o tym wiedzą”[7]. Jak z kolei zauważył Emil Cioran, wszystko, co nas krępuje, pozwala nam się samookreślić – podobnie jak rzepowy kombinezon postrzegany jako metafora skóry.

Marta Smolińska

[1] Porównaj: Thinking Through the Skin, ed. by Sarah Ahmed, Jackie Stacey, London and New York 2007.

[2] Vilém Flusser, Haut, w: Flusser Studies 02, http://www.flusserstudies.net/pag/02/flusser-haut02.pdf, dostęp: 08.04.2017.

[3] Zobacz: Barbara Maria Stafford, Body Criticism – Imaging the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine, Cambridge and London 1991.

[4] Atsushi Tanigawa, Horizonte einer Theorie der Haut in der Kunst, w: Gesichter der Haut, hrsg. von Christoph Geissmar-Brandi, Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit, Satô Naoki, Frankfurt am Main und Basel 2002, s. 23-24.

[5] William James, Essays in Radical Empiricism, Cambridge 1976, s. 86.

[6] Giorgio Agamben, Tożsamość bez osoby, w: idem, Nagość, tłum. Krzysztof Żaboklicki, Warszawa 2010, s. 61.

[7] Zygmunt Bauman, Ponowoczesność jako źródło cierpień, wyd. II, Warszawa 2000, s. 255.

ENG

An (in)tense condition of skin

Skin is the vehicle for thought in the artistic works of Justyna Olszewska.[1] This attitude makes one think of the views expressed by the philosopher Vilém Flusser, who was the originator of philosophical extended dermatology, a discipline dealing with skin as the boundary between oneself and the world.[2] Flusser argued that we must change and become superficial so as to encroach on the realm of theory right from ourselves and see everything ecstatically from the perspective of our bodies covered with skin. In his view, we ought to be interested in surfaces, not in the mysteries supposedly hidden beneath them, since the mystery is not concealed deep down, but it lingers on the very surface of the skin. The skin appears at times to be a ‘space-time continuum’, throbbing in parallel with time, extending and converging in the third dimension, without losing its superficial character. Moreover, it works as if it was ‘my memory’, recording the wounds in the form of scars and other marks. Flusser declared that science and western models of thinking were in crisis, since they were based on objectivity and transcendence by means of which the experience and information obtained owing to the phenomenological perspective could not be expressed. This ineptitude makes us alienated from our own skin: we feel as if it was something alien to us and as a result we also feel alienated in the world. To reverse this process of alienation, Flusser suggested using philosophical dermatology as a tool and remedy. Drawing a map of the skin and developing extended philosophical dermatology should also, in the view of the philosopher, result in the emergence of new models of thought and science, so greatly needed these days.

Olszewska’s work revolves around the skin perceived as a particularly tender boundary between oneself and the world. In our lives so much may happen every single day on its surface – on average from 1.5 to 2 square metres of skin covering the body of an adult, constantly exposed to touch. Barbara Stafford has proposed to extend the dermatological project of Flusser in order to include aesthetics by promoting the notion of aesthetic dermatology.[3] Atsushi Tanigawa, by contrast, postulated a debate on the semiotics of skin, given its role as the place of extremely complex exchanges and transfers between the inner and the outer.[4] In her recorded performances and objects, Olszewska carefully tracks down and arranges these transfers: the project exhibited at present in the Wozownia Art Gallery presents velcro straps used as an equivalent of skin.

Velcro, a fabric produced in imitation of burrs, is known for its ability to cling to nearly everything. It is sticky and immediately interacts with whatever comes its way, ‘catching’ and accumulating things that happen to come close, or clinging to beings and objects on the move. In nature, burrs are the fruit of burdock: in the process of evolution, they developed tiny hooks on their surface which cling to animal fur, thus aiding seed dispersal.

For Olszewska, burrs and velcro serve as a metaphor of skin as a boundary between oneself and the world, a place where extremely complex processes are taking place every day. These processes may involve spectacular encounters with someone else, delightful and painful alike. They may also take the form of ephemeral and subtle relations with dust, our falling hair or cat’s hair, gently floating around and huddling us like a warm woolly coat. In fact, our skin lives its own intriguing life – we notice only a very small part of it, without going so far as to say that this part is merely fractional, although we are all covered with it. The skin in Olszewska’s works, as if seen through a magnifying glass, becomes ‘sticky’: on the one hand, the skin makes it possible for us to be connected to other people or our environment, while on the other, it may painfully separate us from them. The moments when the velcros come together intensely draw our attention to the situations where the skin touches something, or comes in close contact with it, and subsequently – having remembered this encounter by means of touch – it comes off and rebuilds the boundary which so hermetically binds our bodies. For this reason, the sound of ripped velcro straps plays an important role in the lower hall of the Wozownia Art Gallery – it reverberates both as a signal of detachment after a moment of closeness, and as a song of relief or release, one which heralds the regained autonomy of returning safely to one’s own skin.

‘The body is the storm centre, the origin of co-ordinates, the constant place of stress in all that experience-train. Everything circles round it, and is felt from its point of view’.[5] The perception of such works takes us to the sensory-motional sphere – at the core of this process lies the intensity of feelings, with the additional acoustic emphasis, rather than a dispassionate analysis.

This focus on the surface and skin, so popular today, has been inspired not only by research in psychoanalysis, but also by the metaphors developed by Paul Valéry and other writers who defined man as an ectodermic being, a being whose actual depth is paradoxically its very skin. This shift of interest from the depth to the surface, as well as that from the inner-outer dualism to the ‘in between’, is related to our approaches to defining present-day human identity. This is what Olszewska’s works tell us: set in pure white and thus even more forcefully drawing attention to the heart of the matter, they present skin as a space-time continuum, one which makes it possible for us to get in touch with the world and other people. The skin is given autonomy and ostentatiously draws attention to itself. To paraphrase Descartes, Olszewska seems to be saying: ‘I have skin, therefore I am. My being is (in)tense.’

Skin, when not reduced to the preposterous arabesques of fingerprints (as Giorgio Agamben puts it[6]), becomes a map of individual experiences whose individual topography resembles the text of a diary written by impressions. Each skin is unique and one-of-a-kind: strewn with scars, abrasions, speckles and other marks. The process of alienation described by Flusser is thus reversed by the presentation and analysis of skin. What is more, this process makes it possible to express the experience and information obtained owing to the phenomenological perspective. The velcros used by Olszewska also have their own ‘scars’: they are torn and shredded here and there, which can be seen on the overalls used previously in the recorded performances (now presented as an exhibit). Much like the living skin, they bear traces of interactions and transfers taking place on the boundary between the ‘I’ and the world.

The motif of skin, despite its superficial nature, sets in motion the complex and multi-layered strata of meaning related to the following phenomena: the wavering on the inner-outer boundary, the allusions to our fragile physical nature, and the attempts at defining identity in the post-modern era. It also makes us think of our mortality and our vulnerability to various sorts of injury and illness. Finally, it questions our relations with other people and the environment in which we live. By taking up this motif, Olszewska seems to suggest that ‘whatever counts in human life, it counts only because human life has an end and because people know about it’.[7] Emil Cioran once remarked that all our constraints help us to define ourselves. We might add that it is not unlike velcroed overalls perceived as a metaphor of skin.

Marta Smolińska

[1] Cf. Thinking Through the Skin, ed. by Sarah Ahmed, Jackie Stacey, London and New York 2007.

[2] Vilém Flusser, Haut, in: Flusser Studies 02, http://www.flusserstudies.net/pag/02/flusser-haut02.pdf, accessed: 08.04.2017.

[3] Cf. Barbara Maria Stafford, Body Criticism – Imaging the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine, Cambridge and London 1991.

[4] Atsushi Tanigawa, Horizonte einer Theorie der Haut in der Kunst, in: Gesichter der Haut, hrsg. von Christoph Geissmar-Brandi, Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit, Satô Naoki, Frankfurt am Main und Basel 2002, pp. 23-24.

[5] William James, Essays in Radical Empiricism, Cambridge 1976, p. 86.

[6] Giorgio Agamben, Tożsamość bez osoby [Identity without the Person], in: idem, Nagość [Nudities], transl. [in Polish] by Krzysztof Żaboklicki, Warszawa 2010, p. 61.

[7] Zygmunt Bauman, Ponowoczesność jako źródło cierpień [Postmodernity and Its Discontents], 2nd ed., Warszawa 2000, p. 255.

Przypisy

Stopka

- Osoby artystyczne

- Justyna Olszewska

- Wystawa

- Części pierwsze

- Miejsce

- Galeria Sztuki Wozownia, Toruń

- Czas trwania

- 26.05 – 18.06.2017

- Strona internetowa

- wozownia.pl