To Work as a Pixel. Interview with Hito Steyerl

Łukasz Zaremba: One of the many challenges faced by anyone who tries to write about your work is the issue of overcoming (or at least gaining some distance to) the language you use – and by that I mean written language. At the same time you’re not an artists who tries to fix an interpretation of your work in writing. It’s rather that your texts and images form a relationship that is neither hierarchical nor symmetrical – the essays are supplements but never illustrations of the video works. Do you think about yourself not only as a visual artist or filmmaker but also as a writer?

Hito Steyerl: I was always writing. For a long time I supported myself as a writer, a journalist. Maybe that’s one of the reasons why I try to make sure that my articles are never illustrations of my video works. Another reason is my training as a visual artist. I was taught that the image should never be an illustration of a text, so I think in a similar way about my writing – it should never be an illustration of my images either. There should be a tension between them. It’s all about keeping tension and respect the autonomy of each language.

On the other hand – if you look at it from a very basic point of view – currently we have to accept that both text and image did collapse into data. So they are basically made of the same material. That’s why trying to enforce a fundamental difference is even not supported by facts anymore.

In his essay about your work, Sven Lütticken offers a formula that in his view underlies your visual experiments. In his opinion, your work is „hyper‑speculative” precisely because that is the most adequate response in times of „hyper‑capitalism” based on speculation1. I feel this is an extremely accurate description of both your textual and visual work, but I was wondering whetherthere is a difference in being speculative in image and being speculative in texts?

Maybe I would rather underline one important similarity between the two. I think that my approach toward these forms of expression – I wouldn’t want to call it a methodology, but let’s say approach – is the same: it’s a matter of projection. I try to project a question. It often takes the form of an experiment, a “what if”. And after asking this question we construct the model, we test the hypothesis – and sometimes we do it to absurd lengths. So the approach is to project something on a nonexistent future.

Recently I went back to the last book by Villem Flusser, not a very popular book, titled From the Subject to the Project. Becoming Human (2000). That is where Flusser develops the theory of projection – and in this sense my work is performed this way: from a subject to a project, my project of speculation.

In this case, let me ask you about one of the works shown in the exhibition „Abstract” in Wyspa Art Institute in Gdańsk – the video manual for being invisible in the contemporary world, How Not To Be Seen. A Fucking Didactic Educational.MOV File (2013). As we all remember, in the original Monty Python sketch, there is no chance to hide2. Even if you hide well, your neighbour is going to tell „them” and you’re going to die (as is the neighbour, by the way). At the end of the sketch, we discover that the person in power is simply crazy. But the sketch seems to address the problems inherent in different times. In your movie, where the voiceover is similar, the outcome of the experiment – or the result of the projection as you just put it – is in a way more optimistic (we can hide and stay alive), but the way the power works in the visual field is much more complicated. What is the base of this current scopic regime?

It’s just a given fact, that our system of visuality rests in the digital base. Mainly and almost predominantly. But of course it is a very recent development. This development was momentous. It happened so quickly. Just imagine that fifteen years ago very few people used the internet. In my works, I try to describe these changes, and I’m convinced that the result of these changes must also be the change of the description of the relationship between power and visuality.

And so do the tactics of escaping the dominant visual powers and order.

Yes, and what’s striking is that some things I’ve written a few years ago are already sometimes incorrect, because the changes are so fast. That’s why I always try to refer to the current moment. And maybe overtime it may create a picture of the changes.

One of the dates you offer as the symbolic beggining of the new visual order is 1989. In a recent article Too Much World3, you comment on the Romanian revolution of 1989 and the moment when the TV station was taken over by the protesters. You write: “around 1989, television images started walking through screens, right into reality”. Contemporary images “went offline”.

Yes, it probably started around 1989. And we have to comment on what I mean by “images going offline”. But what’s interesting [in the context of the place we’re now – the Gdańsk Shipyard, where the Wyspa Art Institute is situated – przyp. Łukasz Zaremba] is that for example sometime around 1989 the MPEG format was invented (Moving Picture Expert Group – the company was founded in 1988, and the first standardised format of coding was established in 1993), one of the main ways of storing any sort of digital (visual and audio) information.

One of the elements you point to in this new visual order, is the issue of image quality. This is where we can look for change, where the fight against the dominant model of visuality could take place. You want us to follow the poor image in its fight against the dominant, exclusive, HD image, which excludes so much content, and disguises exclusion under a rhetoric of aesthetics. Poor images give us a chance to build communities, to broaden the amount of significant content. But we may also argue that the aesthetics of poor quality was hijacked by the dominant forces right away, for example in 2005, the year of the launching of YouTube. The “reality effect”, aesthetics and “authentic” quality of home movies was immediately intercepted by add agencies.

This relates to the issue of temporality I already mentioned. Technical developments are so fast – moments appear and disappear quickly. I wrote my essays on the poor image when P2P networks seemed to work effectively [peer-to-peer – communication model in which all the nodes are equal and there’s no centre, such as Kazaa or Freenet – przyp. Łukasz Zaremba]. Of course, they still exist today, and some sharing platforms are still used, but they’re not as important and central now. The aesthetics also change really quickly. There is absolutely no reason to think or even to hallucinate that nowadays any sort of aesthetics could present a political opportunity for us for longer than two or three years, simply because things change so quickly. Also: poor images hardly exist anymore. Look at your phone, it’s a high resolution screen. It probably records in HD, does it?

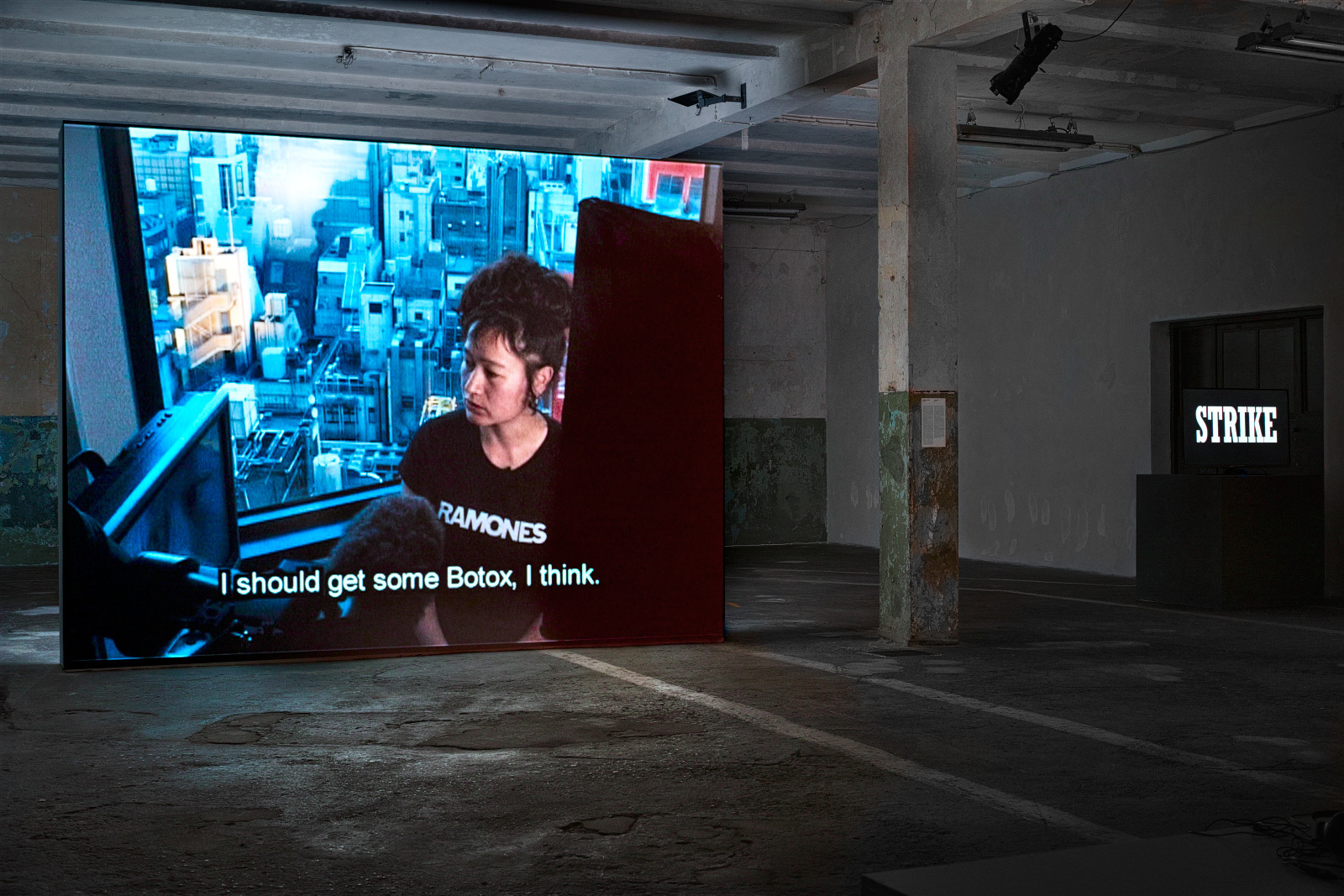

I hope it does… At the same time you’re not anti-digital or iconoclastic – well maybe apart from the playful, ironic work Strike (2010) also shown in Gdańsk4, in which you destroy an HD TV set with the iconoclastic hammer, But at the same time you show us a recording of that act on a TV located in a gallery space.

Oh yes. And even Strike is for me the act of production: you destroy the surface image but you reveal the matrix. You see the base of the image production, the base of the image itself. It’s an act of production, not of destruction, but of course it’s ambivalent. I would never tell anyone that they shouldn’t watch television, even if I think that way personally.

The idea of poor images is so interesting partly because it goes both against dominant common sense intuitions and against dominant theories of powerful visual images, that are supposed to have a direct, simple, mimetic impact on their viewers. Poor images are often everyday images, transparent images. They’re also counted in billions. Which leads us to the question of numbers, reproduction and circulation of these poor, highly available, but often overlooked images. Where should we look for models of thinking about the circulation of images? How should we understand your term “circulationism”5?

It’s important to remember that circulationism is a description of a situation, not a program or method. It’s a description of a situation, in which the currency, the value of the image is determined by its velocity and ways of spreading, but also its emotional charge. And of course people try their best to have their images perform well in this race, as if they were athletes. It’s like a reality TV series: you have one billion runners starting the run through the field of mud and fighting one another, and at the end only one or two will cross the end line.

This opens the perspective according to which the field of circulation is not only to be analysed; it is in fact – and that also comes back to the issue of the poor image – the field of circulation that seems to be the field of intervention! We have to ask how are the circles organized, and whose circles are they anyway? Who owns the infrastructure? Who’s wi-fi are we using? What are the material connections within the networks, the nodes? What are the power hierarchies within the circulation infrastructure itself?

To add something on the topic of the poor image – I think that right now the question of poor infrastructure should be of as much importance to us. What kind of alternate infrastructures for circulation could we imagine? For example, many alternative web structures have been opened in places, where there is no adequate wi‑fi. These are examples of self-organized and self-constructed infrastructures, someone’s own internal internet.

The question of finding alternative models of circulation is equivalent to the question of the poor image. We have to ask how basic materials – like water or wind for example – in fact possess a huge, unexpected impact on networks, on the digital framework.

And we can ad to that things like labour or energy. We’re used to thinking about the internet as flawless, immaterial, and “free”. In fact the internet possesses a very material base, a physically existing infrastructure. It also involves multiple kinds of labour, just to mention the labour of the user, who acts as the a data generator.

Yes, in a way we are the resource – the source of the energy, feeding the system.

Although, as you mentioned,circulationism is not a program, I feel that the amount, the location and the role of images makes one think about the distinct role of visual experts: for example artists or filmmakers. Since there is no strict boundary between images and the “real” world, and images do, as you say, “go offline”, those who possess intricate knowledge of the visual would seem to be privileged.

Filmmakers are gradually starting to occupy the role of “world-makers”, engineers of affects and of reality. On the other hand, I happen to be trained in this craft, and I have to say that I don’t have any superior qualifications over anyone else nowadays. It really has become a universal skill. It’s also become the field of industrial labour, because not many specialist skills are required.

But isn’t that also a certain limitation? Most of us nowadays are able to work in frames designed for us, with a limited number of tools provided, limited potentiality. That’s how these programmes and applications are designed. They’re built on the premise of dividing levels of access – most of us work only with the surface of our favorite app, graphic program etc.

Of course. Now one can even find a film editing algorithm. You can basically upload your footage and it works through the night and in the morning you have your movie ready. It’s not bad. But I really think that in a way being an artist became a universal qualification, and some people simply should get over it.

In his book The Migrant Image, the American art critic and theorist T.J.Demos describes your work as an example of an instance where the material, visual condition expresses the condition of those who are represented or visualized, the subjects whose condition (for example a certain lack of agency) becomes the subject of artistic expression.

There is one decisive difference between what we could call a theory of the politics of representation and my work. While the politics of representation always thinks about the image as an image of something else, I think about the image simply as something. Also, the relation between people and images is not simple. And certainly people are not victims of images.

So what does it mean to identify with a JPEG or pixel?

Recently, I read this beautiful quote from a protester in Kiev. He literally said: “I have to be here, working as a pixel”6. He described his protest work, organizing Maidan, as the work of a pixel in a sort of a mediatized mass movement. This did not mean that the movement was mediatized afterwards, in the process of reporting about it, but that it is produced as mediated, as pixels in the first place. What he said – “this is my job, I work as a pixel” – really struck me. Of course the idea of identifying with a pixel is ambivalent. I’m not trying to say that this should be the final move, the solution to our problems. I do think that this is a position one can occupy today, one providing opportunities that are worth exploring. The fact is this condition exists, we cannot avoid it. We can criticise it, we can work against it, but we have to work with it, we have to take it into consideration.

A short art magazine note7 announces your exhibition in Wyspa in a language typical of this art-world genre: “The upcoming Hito Steyerl exhibition is a feast for art enthusiasts interested in art that explores post-digital reality”. You are also called one of the “classical authors of this field”.

Of course, the classical age started six years ago and it was over already yesterday.

Yes, the first thing that this short text brought to my mind is that of becoming a classic in such an arena. For example, currently on view at the Warsaw MoMA there is a show titled “Privacy Settings. Art After the Internet”8, which presents the work of artists from a certain generation – the so called “digital natives”, born in the 1980’s and 1990’s. The second question is a question about the relation of the prefix “post” – post-cinema, post-digital – and what you call the “dead internet”.

Let me use a phrase that in my opinion gives a good answer: “The internet is not over, it’s all over”. It’s all over the place. The temporal “over” reflects the end of the pioneer euphoria about the possibility for free sharing and horizontal information. But as I said, there are always new possibilities, always new things emerging. And saying that the internet is something from the past would be like saying that reality is over. A statement like that doesn’t have any sense. The internet is a part of the condition of our lives. We have to deal with it. A lot of interesting things can still be done. And I really am fascinated by the work of this new generation. Never before has a generational change been so meaningful – in their art, they deal with the reality that was hitherto sidelined within contemporary art. Not that I like all work that is being done, but as an overall phenomenon I do think it’s very important.

In short essay about Kobanê you recently published, you described a discussion you participated in during your stay in Turkey. While you were debating art there were F-16 jets circling above your heads9. You end the article with a question: “What is the task of art in times of emergency?”. It seems like a very general question, but one that can be supplemented with other important ones. Like: What is the value of visibility?

I don’t think this question can be answered in a definitive way, one which says that visibility is always good or it’s always bad. This is what How Not To Be Seen… is all about. Sometimes being invisible is really vital, sometimes disappearing can save your life. Sometimes disappearing is the effect of loosing your life, of being killed. It would be foolish to provide a general manual of being visible and invisible. But one thing that I think is remarkable – that the discussions went on and continue, that’s really crucial. They continue building the field of experience. And let me just add – the expression at the end of the text emerges from the discussion. During my stay in Turkey, one of the curators asked me that question and it stuck in my head and I can’t stop thinking about it. Art in times of emergency. The act of circulationism: questions that are being carried around and that energize other places. Not only images can play this role.

Przypisy

Stopka

- Osoby artystyczne

- Hito Steyerl

- Wystawa

- Abstract

- Miejsce

- Instytut Sztuki Wyspa

- Czas trwania

- 16.10-31.12.2014

- Osoba kuratorska

- Aneta Szyłak

- Strona internetowa

- wyspa.art.pl