Historical carriers of vital DNA. Interview with Marinko Sudac

Karolina Majewska-Güde: Marinco Sudac collection comprises of around 10 000 objects – various works ranging from Japanese avant-garde, prints of Apollinaire to Eastern European conceptualism. The beginning of your practice as a collector- its first local stage -was related to your interest in neo-avant-garde art practices in post-Yugoslavia region. What idea holds this heterogenic artistic material together?

Marinko Sudac: I don’t see my collection as a compilation of inventory units, but as a unique system of equal elements. In this regard, the collection has an enormous amount of units in museological terms, divided in segments by countries, artists, and phenomena from 1909 to 1989. In other terms, on historical Avant-Garde, postwar Neo-Avant-Garde, and new artistic practices of the late 60’s, until the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Today, after ten years of collecting this type of art, which was in wider, even professional circles, unknown, invisible, and hidden, I can say that the ideas, as well as the Collection’s strategy, have become an important cultural aspect of the entire region. The basic premise of gathering and affirming the art in the Collection is today my obligation and field of interest, and the instinct with which I went into this project has in the meantime spilled over into my everyday life and became my way of life. Sometimes I feel as if I had lost my identity and live the identity of an artist in my collection. I coexist in the life of artists, some of them not longer present. With those still present, I am in frequent contact. I want to give this experience to the public too.

1989 became for you a very clear caesura. Why did you defined a timeframe in such a rigid way?

That is the moment of a great political and cultural turn. Europe united politically, and the radical art practices became fully integrated in the art mainstream. I think that is the moment when the „misfit“ art, which I am interested in, disappeared. What is left are the occasional sparks of the artists of the neo-Avant-Garde period. My desire is not only contribute to the efforts to record this period, but not to forget the lessons from history about art and life. I want to inspire the artists of the younger generation to foster the rebellion and the desire for change in their artistic practice.

However, in the time after the fall of the Berlin Wall, after Russia and Yugoslavia split, Europe became different and something completely unexpected happened. When you try to understand the ideological message of historical artistic Avant-Gardes, you see that the relation between art and politics has in a way shifted in the field of esthetics and that those genuine ethical messages, those that ontologically hold the art of historical Avant-Gardes, had been suppressed. With the expansion of neoliberalism art shifted to the field of market, it became a sophisticated good, defined by the strong idea of the market. In the moment in which in place of art comes culture, or when culture puts itself in the center of art through the postmodern prism, there is an incredible triumph of aesthetics, of aesthetic formalism, in which the core messages of art and artist are hidden.

So, this caesura is related to the particular interpretation or, as I understand, your negative evaluation of contemporary global art?

Circumstances of artists in the communist countries where the Avant-Garde movements were dominant, can be seen as cautionary and despairing in every context, especially in that personal, material, status of the artists who live and create on the verge of survival, poverty, holding on with ascetic conviction to the idea of keeping the core ideals of art, which are the de-subjectivization of the public sphere, and, above all, ethics. The artists manage to somehow cope with those historical lessons until the caesura of 1989. This is the year that represents a turning point in art because then, art slowly started drifting towards the traps of technology, the transformation of body in the digital space of the Internet, there was an evident dehumanization.

The artists present in my collection are historical carriers of this vital DNA, which by some strange historical mechanism reappears carrying the primary material of culture. This is the most important dimension which my collection wants to present. To have it gathered in one place for me represent a great universe filled of spectacular biographies, occurrences and phenomena. The contemporary context, in the ideological sense, aids the collection.

The core of your collection can be defined as Eastern European neo- avant-garde. But I’m also interested how you make particular choices. Do you work with advisers/experts?

The core of my collection is the Avant-Garde art that had crucial impact on the visual culture we know today and that was unfairly neglected and forgotten. This is especially the case with Eastern European Avant-Garde and Neo-Avant-Garde which, in due thanks to my efforts, is now becoming more known and valued in the global narrative of 20th c. art. Avant-Garde artists always had strong international contacts and exchanges with each other – probably because they did not feel excepted in their surroundings, so they looked for like-minded individuals all across Europe. Those contacts could not be cut even by the political divide on the East and the West, but the Eastern European Avant-Garde was still under the radar of Western experts, and in its own surroundings it was prosecuted, not valued, due to its opposition and critique of the reigning regime. Now is the time to right this historical injustice. I work towards this goal by choosing artists who were completely disregarded in their own surroundings, I organize their exhibitions and create monographys, and so I give them their deserved place in history. Of course I have advisors; I work with leading experts in the area of my interest. Over the years, we started to have not only professional, but also private connections. During my research, I had discovered many artworks and artists which even they were not aware of and so we have developed a mutual bond of personal and professional appreciation.

In our previous conversation you have mentioned ‘anthropologic approach’ as your strategy. You have also said that you know an art work twice – before getting to know an artist and after getting to know him/her. Why is personal contact with artists so important to you?

A significant part of choosing the artist is instinct, but what determines the shape of the collection and choice of artists is, above all, the realization that those people are utopists, almost at the verge of being understandable, especially when you take into consideration the context they are coming from and in which they created their art. They were always castaways, always in some conflict, always radical, always pure in moral.. This intertwinement of the everyday and the utopian ideas of a different world is the key of understanding the strategy. So, it is not me that is setting up this strategy, but it is set by the artists whose footsteps I am following now. The friendships that are created are more then pure sentiment, they are raised to the level of moral act which guarantees that, at a certain time, and those works will be rehabilitated and put in their rightful place in the cultural history of the world. So, the artist is the most important part for me. I value the strength of radical artists to live within their own, uncompromised, worldview, even if that entails political prosecution and, often, poverty. I value that they are proudly living the fact that the institutions and professionals disregarded them, forgot and undervalued, and still they had stayed the same idealistic individuals who, in their youth, started changing the art and the reality around them. When you consider that Avant-Garde art strives to put art and life on the same level, this is actually the key criteria of artistic credibility and force of vision.

Do you consider yourself an ‘idealistic individual’? Since, as you suggest, not owing the works but rather writing ‘global art history’ i.e. using the role of a collector to ‘give a justice’ to the unappreciated Eastern European artists became your ultimate aim.

In today’s world, in countries such as Croatia, collecting has been raised to the level of social responsibility and reconstruction of national identity. Globally, collectors shape the art scene so the line between private collectors and public museums has been erased. They work together and with that synergy they strengthen the art scene.

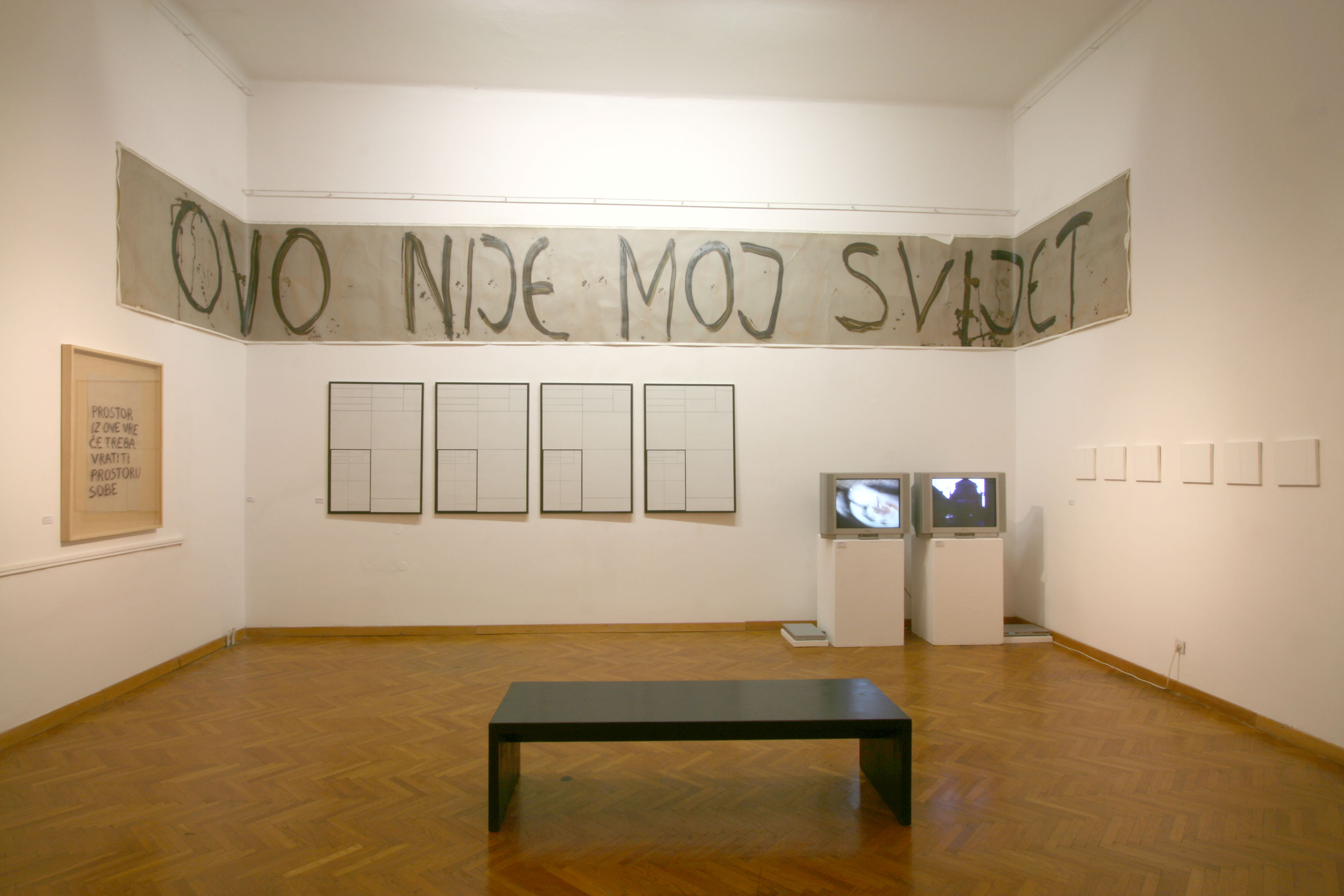

As for my collection, it is shown in museums or spaces of historical significance or in completely anonymous spaces. The fate of the Collection is based on the quality of its content, and its future is certain only with of the future physical museum. So, it needs to be present in the public and seen constantly. All the projects we are creating have as their goals the affirmation of the Collection – not of its size, volume or scope, but the affirmation of the historical significance of the works in it, which is, in the eyes of art historians, seen as invaluable. This is the idea that drives me in my work.

Indeed your practice as a private collector echoes methods and objectives of a public art institution. We are talking not only about comprehensive on-line catalogue, a research program (Institute of Research on Avant-garde), but also about extensive documentation and publishing. Recent monography on Gorgona group you’ve also edited yourself. In other words major part of your effort involves creating infrastructure that produces a historical and critical discourse about the works you own.

As I previously mentioned, I want that these forgotten artists and art get a place they deserve and be respected. I want to give the position they deserve in the context of the international systems of art and culture. I want to publish an array of unknown facts which I found in the course of my research, going though documentation and talking to artists. I want to make known individual experiences and stances of curators, who have spent their entire lives promoting art which was not understood. After all, it was our scene which combined the top artistic production with the theoretical background and critical thinking. One cannot go without the other.

You put also a lot of energy into gaining public visibility for the collection, especially through the website. What is the relation between the collection and the virtual Museum of Avant-Garde that we can see on the website?

MS: Just as to any collector who has a vision, I too feel that it is important that as many people as possible see the art that I collect and love. Since there is still no physical building of the Museum of Avant-Garde Art, I had decided, inspired by the love of Avant-Garde artists towards technology, to use the possibility to present the collection in virtual reality. So it came about, with the professional help of my associates and an innovative web design, as the Virtual Museum of Avant-Garde in which, for now, you can see only around ten percent of the Collection, learn basic information on the artists I’m interested in, but also read about the projects I create through the platform of the Institute for the Research of Avant-Garde. The plasticity of the digital medium enables an easy presentation of the connections between certain artists and phenomena in time and space; it opens the possibility of presenting multimedia content and documentation. I had come to see that the virtual space requires as much effort, even financial funds, as a physical space. The Collections structure and, as I’ve said earlier, ten percent of its content is already available on www.avantgarde-museum.com, but there is still a lot of work in front of us on the digitization of all the materials and putting it on the website. We are working on it as much as we can with our temporal and financial limits. The Collection has its website, or in other words, a part of it is digitized, but the work of the Institute is really important at this point. This is because we are slowly extracting, one by one, all the phenomena from the subconsciousness of the European culture which helps us better understand history, as well as the present time. This visionary dimension the artists of the period had is just incredible. The relation between the Collection, its material and virtual aspect is, in fact, similar to the ideas of these artists who had then, in some metaphorical manner, placed their ideas in the sphere of the virtual, or the sphere of the future, today’s present. As if they knew that, in the future, they will be greeted by art again. This transference between history and the present is seen in the phenomena of the Internet. Of course, the virtual museum is a place from which we can move towards physical reality, because there is something extremely tactile in the papers, drawings, sketches, works, letters…, something that cannot be shown by digitalization alone, this material must be physically presented to everyone and visible in the future physical location of the Museum. These are the mediums in which lie the answers on the human contributions to this incredible epoch we call – the Avant-Garde!

4. Presentation of the Virtual Museum of the Avant-garde Art to the world’s leading museum professionals – Standing from left to right: Robert Fleck (then director of “Bundeskunsthalle”, Bonn), Tihomir Milovac (Senior curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb), Kwok Kian Chow (National Gallery of Arts, Singapore), Kasper König (Ludwig Museum, Köln), Želimir Koščević (member of the Board of the Virtual Museum of the Avant-garde Art), Zdenka Badovinac (Director of the Modern Gallery, Ljubljana). Sitting from left to right: Marinko Sudac, Manuel Borja- Villel (Director of Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid), Sheena Wagstaff (then chief curator Tate Modern, London), Sabine Breitweiser (then curator, MoMA, New York) i Pilar Cortada (Curator, Museum of Modern Art, Barcelona)

Another project which utilizes a strategy typical for a public art institution is a very specific artist residency called Artist on Vacation.

I am a workaholic by nature and I don’t know the meaning of vacation, which for most people is their favorite time of the year. I want to create a setting in which I can collaborate with the artists I know or want to get to know, and be relaxed and not weighed down by the routine of everyday work. My experience with the Artist on Vacation Project showed me that the artists themselves have seen this combination of work and leisure as an incentive to create. The project is an integral part of the activities of the Museum of Avant-Garde, Institute for the Research of Avant-Garde and Marinko Sudac Collection, devised in a way to work with the overall development strategy, or its affirmation in the social, cultural and artistic context. So, the project is a tool devised to connect all the planned activities taken to familiarize the public with the Avant-Garde in a direct way, outside of the official institutions of museums or galleries. We are also very fortunate to work with a company such as Valamar Riviera d. d., which recognizes our mission and is a socially responsible company.

There is always an exhibition at the end of each edition of Artist on Vacations. How do you see your position in the context of exhibiting artworks from your collection? Do you act as a curator of these shows?

The exhibition is a mix of documentary material on the Artist on Vacation Project itself, as well as the new works created in Valamar Riviera d. d.‘s Resorts. As part of the Project, there is always an exclusive one-day exhibition organized in Valamar Riviera d. d.’s locations, and these exhibitions are something any official museum institution could be proud of. Each artist manages to integrate their artistic strategy to the context they come in. I am the creator of this Project, and the curatorial part of the work I leave to my associates. This relation varies on each of the exhibitions we organize and it is very dynamic.

What about other exhibitions you have organised or participated with your collection?

One of the exhibitions I would like to mention here is a retrospective of Aleksandar Srnec, which was the first exhibition in the newly opened building of the Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb, on which there were over 4 500 people at the opening, and 54 000 in total who had come to see the exhibition. I also organized an exhibition on Tito’s boat Galeb (Seagull) called At Standstill in 2011 in Rijeka, an exhibition and lectures “OHO After OHO”, exhibition Avant-Garde Art and the First World War on which many students worked and had a chance to show their ideas and knowledge in practice. Works from the Collection have been exhibit in Varaždin, Rijeka, Novi Sad, Istanbul, in Frankfurt on a retrospective exhibition of Avant-Garde film…

Some works from the Collection, Bucan Art series by the artist Boris Bućan, will be exhibited in September in Tate Modern in London on the World Goes Pop exhibition. In the beginning of next year, some works will be in an exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary. Also, this year works from the Collection will shown in Ludwig Museum in Budapest on Ludwig Goes Pop exhibition. This will be the third time that the Collection is exhibited in Budapest – there was the exhibition Circles of Interference in 2012 in Kassák Museum, Transition and Transition with work by Josip Vaništa, Oleg Kulik and Blue Noses, in the Ludwig Museum in 2014.

At the end I have to ask this question: in your collections there are many works of Polish artists: Natalia LL, Andrzej Lachowicz, Zdzislaw Sosnowski, Teresa Tyszkiewicz; this year you have been working with Przemysław Kwiek and Ewa Partum. Why did you chose these particular artists?

Poland is a great nation. We know of its contribution to Constructivism, the beginnings of Avant-Garde, we know of artists such as Władysław Strzemiński, Katarzyna Kobro i Henryk Stażewski, and all that followed. The first exhibition of works from my collection was in the city of Varaždin, Croatia in 2005. This exhibition showed the continuity of Avant-Garde art from the historical Avant-Gardes through Neo-Avant-Garde o new artistic practices ending with the fall of the Berlin Wall. To me, it was clear straight away that I should expand the collection, which was then based mostly on art created in the former Yugoslavia, to include other European countries and even beyond because of its quintessentially international mode of expression. This is why the abundant Avant-Garde production of Poland was a logical choice. Talking about the artists you mentioned, I find one phenomena intriguing. The phenomena that in the case of a divorced couples who were also an artistic duo, women from that couple are the ones that end up getting much more recognition and exposure. I assume this is due to the contemporary interest in gender issues, women’s poetics and creative work, which is also a sign of critics and experts going by what’s trending, and perhaps not merely going by artistic merits. Personally, this is why I find, in the KwieKulik group, him to be a more interesting artist because he paints in the style of near kitsch, which the critics are dismissive about. During Przemysław Kwiek’s stay in Poreč as part of the Artist on Vacation Project, I had come to understand Kwiek’s intention of criticizing the critics and creation from the standpoint of and artist-outcast. Similar examples of this phenomenon, of disregarding the male part of an artistic duo, can also be found with Eastern European couples such as Marina Abramović and Ulay, Nuša and Srečo Dragan, Sanja Iveković and Dalibor Martinis, Natalia LL and Andrzej Lachowicz… This is one example of my, as I unofficially call it, anthropological method.

Karolina Majewska-Güde — Historyczka sztuki. Zajmuje się wschodnioeuropejską sztuką neoawangardową, feministyczną historią sztuki oraz zagadnieniami obiegu, tłumaczenia i produkcji wiedzy poprzez badania artystyczne. Autorka recenzji oraz esejów w katalogach wystaw. Członkini feministycznych kolektywów badawczych i kuratorskich. Pracuje jako adiunkt badawczy w Instytucie Historii Sztuki UW. https://karolinamajewska.